6 Swiss architects who conquered the world

The Olympic Stadium in Beijing, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Blue Tower in New York: these are just a few of the iconic buildings born from the imagination of Swiss architects. Endowed with a clean environment, distinguished schools and public policies that encourage creative freedom, this small country is the birthplace of some big names in world architecture. Below are portraits of a few of these builders with Swiss roots.

"The quality of Swiss architecture is the fruit of a happy marriage between the construction industry and a very strong political engagement," explains Nicola Braghieri, director of the Department of Architecture at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL), himself an architect. The professor compares the figure of an architect in Switzerland to that of a fashion designer in Italy. "The confidence which the Swiss public administration places in young architects is unique in the world," he emphasises. "In Switzerland, thanks to a tradition of competitive tenders for both public and private construction projects, even a 30-year-old architect has the opportunity to build great buildings!"

Bernard Tschumi (1944), the unclassifiable

Bernard Tschumi is hard to pigeon-hole. Not identified with any particular movement, the Franco-Swiss architect born in Lausanne is a master of playful structures, inspired particularly by the cinema and opposed to the rationality of modernism. Until taking charge of the Parc de la Villette in Paris in 1983, Bernard Tschumi was known mainly as a theoretician. The architect's love for the silver screen is apparent in the Parisian park, traversed by a three-kilometre 'cinematic promenade' whose winding course among the themed gardens evokes a reel of film unspooled along the ground. Since then Tschumi has brought a multitude of other important works to life, including the Blue Tower in New York (2007), his first residential tower, and the Acropolis Museum in Athens (2009).

Herzog and de Meuron (1950/1950), the pharaohs

The Olympic Stadium in Beijing (2008), christened the 'Bird's Nest' for its interlacing steel beams, is theirs. The Elbphilharmonie Hamburg (2017), the new icon of the German city, its mind-boggling cost equalled only by its magnificence, is theirs as well. Herzog and de Meuron collect pharaonic projects. The Basel firm of 380 staff and 40 associates was founded in 1978 by Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron, two childhood friends who attended ETH Zurich together. These experimenters love to test new materials and tackle complex problems to give life to their extravagant projects. They were awarded the Pritzker prize, architecture's highest honour, in 2001.

Peter Zumthor (1943), the poet

Together with Herzog and de Meuron, Peter Zumthor is the third Swiss architect to have received the Pritzker prize. Their styles, however, could not be more different. A native of Basel who served an apprenticeship as a cabinetmaker before studying architecture, Zumthor has an artisan's approach. "Peter Zumthor’s buildings have a strong, timeless presence," declared philanthropist Thomas Pritzker at the award ceremony in 2009. "He has a rare talent for combining clear and rigorous thought with a truly poetic dimension." One of his best-known works is the Bruder Klaus Field Chapel in Wachendorf, Germany (2007). The twelve-metre monolith built in the middle of a field was designed by Zumthor free of charge for a farmer, then built by the farmer and his friends and neighbours.

Mario Botta (1943), the utopian

He is the most illustrious representative of the "Ticino School", together with Luigi Snozzi, Aurelio Galfetti and Livio Vacchini, all of whom have won international renown. What Mario Botta shares with them is not a signature but "a privileged rapport with the geography of the places that determine their architectural oeuvre," as he told swissinfo.ch. He is referring to the Italian-speaking region of Switzerland, which is "already an architectural creation in its own right," he says. "Its planes of water constitute a horizontal base against which the verticality of its valleys and its mountains is superimposed." Botta, who worked alongside Le Corbusier, is one of the founding fathers of the Academy of Architecture of Mendrisio, his home town. He has designed over 600 projects around the world, including the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (1995).

Roger Diener (1950), the discreet

Sober and elegant, Roger Diener's structures may seem banal at first glance. It is true that the Basel architect seeks simplicity and discretion. "We strive to establish a correlation between the building and the social cohesion of the city," writes Diener on the website of his firm Diener & Diener, founded by his father in 1942. Roger Diener joined the firm in 1976 as a freshly minted graduate of ETH Zurich. The numerous projects executed by Diener & Diener abroad include the master plan for the port of Malmö, Sweden, (1997), the extension of the Swiss Embassy in Berlin (2000) and the Shoah Memorial in Drancy, France (2012). In 1999, Diener founded ETH Studio Basel, an urban research institute affiliated with ETH Zurich, together with Jacques Herzog, Marcel Meili and Pierre de Meuron.

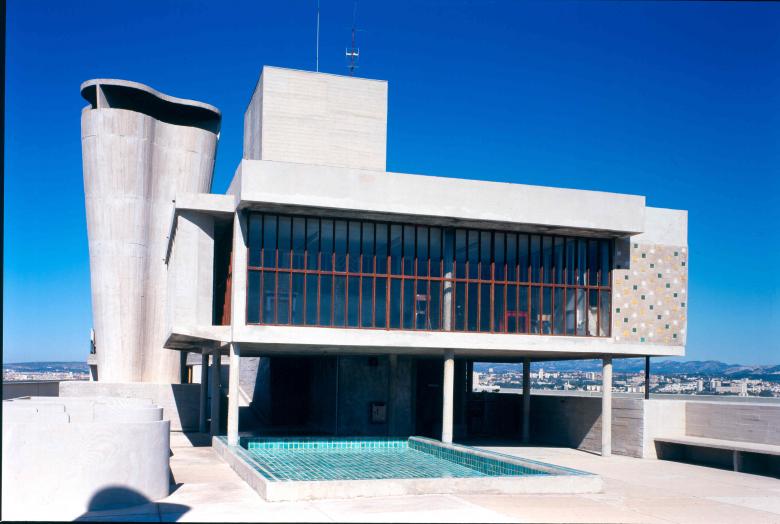

Le Corbusier (1887-1965), the scientist

No discussion of Swiss architecture would be complete without mentioning Le Corbusier. Born in La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland, and naturalised as a French citizen in 1930, the architect built far and wide. Many of his structures are inscribed in the UNESCO World Heritage List. A major figure of modernism, a minimalist, functional architectural movement where iron, steel, concrete and glass are predominant, Le Corbusier sought to apply the methods of engineering to architecture. A great theoretician, he developed the concept of the Unité d'habitation, a housing development meant to conform to human scale, the best-known example of which is the Cité radieuse in Marseilles (1952), known informally as La Maison du Fada (the Nutter's House). Le Corbusier's influence endures to the present day. "He is in the dreams and nightmares of every architect," says Nicola Braghieri of EPFL.