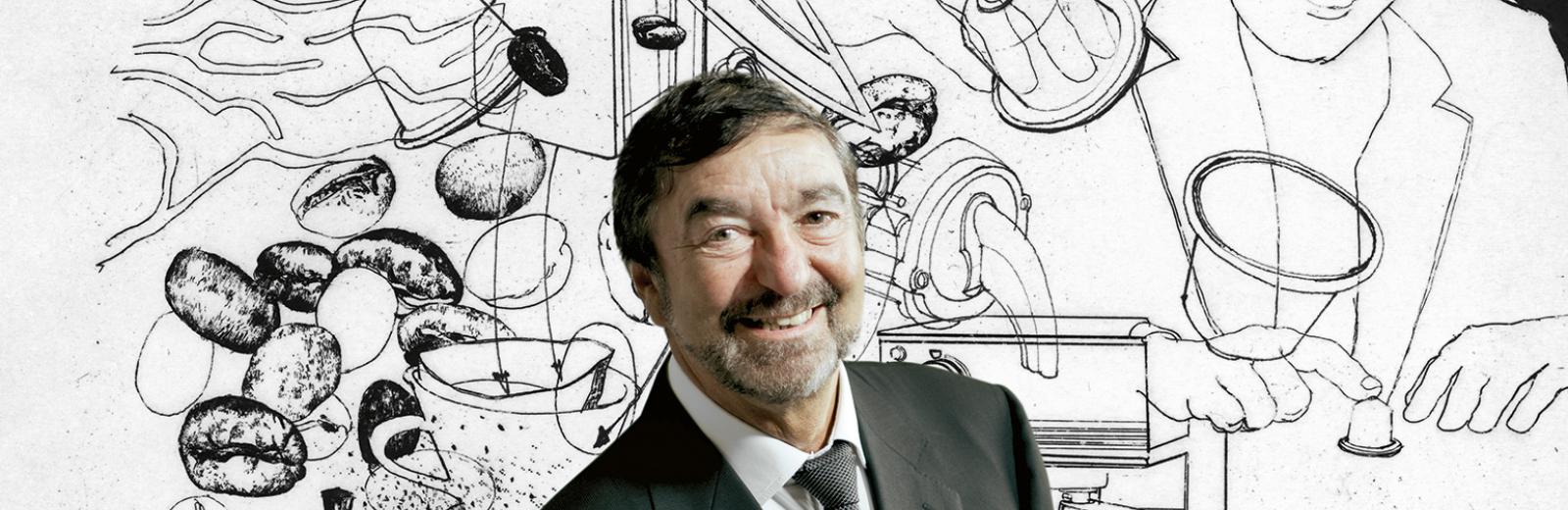

Éric Favre - the Swiss inventor who put coffee into capsules

An aerodynamics engineer from the French-speaking Swiss canton of Vaud is the father of capsule coffee. His innovation completely changed the way we drink coffee and made Nespresso a planetary success.

Inventors are generally modest, while entrepreneurs like to boast about their success. Looking back 40 years on the invention which ushered in the era of capsule coffee, Éric Favre – both inventor and entrepreneur – is quietly "proud" of his achievement. Favre always knew he would be an inventor, but it was his Italian wife who set him the challenge that would make his career. If Anna-Maria hadn't teased her husband about the bland coffee enjoyed by the Swiss, the world might never have tasted Nespresso.

It all started in 1975. Favre had joined Nestlé's packaging department to learn about the workings of a multinational from the inside. "I wanted to prove to my wife that I was capable of making the ultimate espresso," Favre revealed last year. The couple set off to scour Italy's bars in search of the best coffee. Settling for a while in Rome they frequented the popular Caffè Sant'Eustachio, today considered by tourist guides to serve the best espresso in the capital.

The magic formula

Anna-Maria and Éric took to peeking behind counters and questioning staff, until one day barista Eugenio dropped a vital clue. According to Favre, the reason why Italians were lining up to sample Eugenio's brew was that instead of pumping the piston of the machine just once, the barista aerated the coffee by pulling the lever at several short intervals. "It's chemistry: oxidation brings out all the flavours and aromas," Favre explains.

That was where he got the idea of a machine to introduce a maximum amount of air into the water forced through the capsule. Back in Switzerland, the inventor developed a prototype espresso machine – a Back to the Future style amalgamation of tubes and cylinders – before settling on his formula: froth = air + water + coffee oils. Favre invented a sealed capsule in which air is trapped before water is forced through, filling the cup with frothy espresso.

His idea may have been revolutionary, but Nestlé wasn't convinced. Sales of the group's famous instant coffee brand Nescafé were rocketing. Confident that households would stick to their beloved instant granules, Nestlé's management didn't see the need to invest in expensive espresso machines. It would be ten years before Nestlé director Helmut Maucher finally gave Favre the go-ahead to launch Nespresso as a subsidiary company. The first Nespresso capsules came on the market under Favre's supervision in 1986.

They were initially aimed at a specialist business clientele: bars, hotels and offices. The first machines designed for offices and homes were inspired by the huge espresso machines found in Italian bars. In 1984, two models were tested by Nestlé in Switzerland, Italy and Japan. In 1986, Nespresso’s capsule system was marketed as a luxury product. However it failed to catch on, and in 1988 Nespresso repositioned itself to target the high-end consumer market. The more affordable capsules started appearing in Swiss households and two years later they arrived in France and the United States. However, with Nespresso struggling, Favre was forced to leave Nestlé in 1991. He subsequently established several successful espresso capsule companies including Monodor, where Anna-Maria Favre was an influential board member.

The war of the capsules begins

Favre took the opportunity to develop a new generation of incinerable capsules made from polypropylene instead of aluminium. The new packaging eliminated the need for an integrated filter, which was now part of the machine and reusable indefinitely. Meanwhile, Nespresso was really taking off and Monodor was joining forces with Lavazza, and with Migros in Switzerland (Delizio). The story of the capsule's success is also one of fierce competition and countless legal battles. The patent obtained in 1991 for the new capsule, which protected Nespresso until 2012, sparked a series of court cases with Nestlé, which claimed to have come up with the concept. Favre and Nestlé CEO Peter Brabeck finally buried the hatchet with the signing of an agreement in 2003.

Favre is a passionate innovator who was always confident he would go it alone one day. When he joined Nestlé, he embarked on a career as an 'intrapreneur' charged with restoring from the inside an ideal sometimes lost through routine or in the administrative workings of a giant multinational. In his 2014 book How to turn honey bees into money bees (without being stung), Favre wrote, "innovation resists planning and those who seek it have to expect to see the spectre of failure waiting at some turns in the road".

"Although I knew that failure brings those who are ready to learn closer to a solution, I still had to assume full responsibility for my mistakes. Refusing to come up with some sorry excuse or look for scapegoats, I claimed responsibility for the whole thing. So I wrote a letter to my superior saying 'I realise I made some mistakes as Nespresso's director, but if I had refused to risk making any mistakes, the product would not exist today. Of all the mistakes I made, the one I regret most is having taken so long to make the others...'."

In 2015, Favre nevertheless drew a line under his long career. Unable to find a successor or local buyer for his two businesses, at 68 years old, he decided to sell first Tpresso and finally Mocoffee to a Brazilian company. Although he looks back with nostalgia on his days as a businessman, Éric Favre can take pleasure in the knowledge that over half of all coffee capsules bought by consumers worldwide are based on his invention. And Anna-Maria Favre can no longer tease him about his bland coffee.