The national gene bank: safeguarding tomorrow's biodiversity

Humanity's future depends on the diversity of the species living on our planet, as they provide present and future generations with a food source and a healthy environment. In Switzerland, many varieties of plants are stored in the national gene bank maintained by Agroscope, the Swiss centre of excellence for agricultural research.

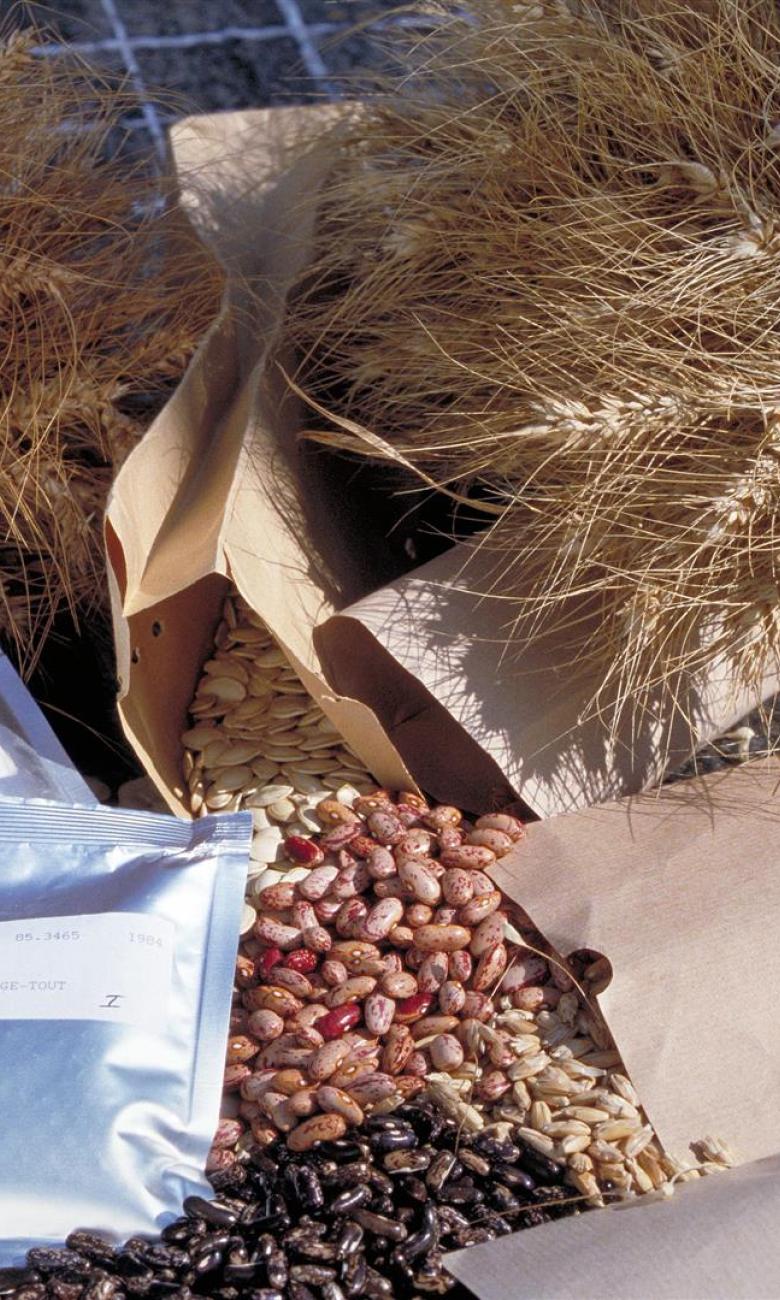

Ecosystems in Switzerland and worldwide are deteriorating as a result of intensive farming, climate change, pollution and other factors, putting biodiversity at risk. Conserving our genetic resources is essential if we are to counter this trend. Various techniques can be used to preserve plant agricultural biodiversity: many species of wild plants and crops are kept in field-based collections, while other plants are stored in laboratories or as seeds. Agroscope's Changins site in the canton of Vaud is home to two libraries of genetic resources: cereal, vegetable and aromatic plant seeds are stored in a seed bank, while fruit tree, potato and vine samples are kept in an in vitro nuclear-stock facility.

One library, thousands of resources

Agroscope employee Cyril Schnewlin opens the door of the seed bank, revealing the dozens of crates lining the shelves of the cold room, which is kept at a temperature of 4 °C. He selects a crate and removes a small paper bag labelled 'Avondefiance'. Nestling inside the bag is a sample of lettuce seeds, one of the 13,000 accessions – samples collected at a particular place and time – of cereals, vegetables and other crop plants stored at the facility. "What we have here is a library of viable seeds just waiting to be taken off the shelves and planted," explains Cyril. These living archives are more than a century old, and still contain varieties collected in the early 20th century. People use the seed bank for a variety of purposes. Researchers sometimes produce crosses based on the old plant varieties stored there in the hope of obtaining hardier or more disease-resistant crops. The seed bank's samples are also used for exhibitions in Swiss botanic gardens, or by farmers looking for old local crop varieties.

The tour of the seed bank continues in the building's basement. To conserve the seeds for long periods, Cyril and his colleagues store them in a huge freezer at a temperature of -20 °C. Before being placed in the freezer, the samples are dried out for several days then vacuum-packed in aluminium bags. This method allows some cereals to be stored for up to 50 years without losing their ability to germinate. Each year, selected varieties are planted and the resulting seeds harvested; these new seeds are used to replenish the facility's collection of cereal and vegetable seeds for the decades ahead. The seed bank is full of curiosities, like the wheat variety that became known as 'miracle wheat' in the late 19th century because its abundant spikelets led people to believe it would give a better yield. Other treasures include goatgrass, which is one of the oldest cereals grown by humans, and 'Ribelmais', a variety of maize that has grown in the Rhine valley for many generations.

© Agroscope, Carole Parodi

The world in test tubes

The in vitro nuclear-stock facility forms a striking contrast to the cold rooms. While the shelves in the seed bank were stocked with crates of seeds, the shelves in the nuclear-stock facility carry hundreds of test tubes bathed in a clear light that reveals their precious contents: tiny plants rooted in a substrate gel. The 'bonsai' plants growing in the lab include lemon, clementine, strawberry, raspberry, lemon balm and oregano. The 400 plant accessions housed here are a valuable reserve for the agricultural sector, as they could be used to restore plant resources if they are wiped out by severe weather or disease.

"Plants propagate more quickly in vitro, as they are less influenced by the seasons," says researcher Eric Droz. As an example he cites the potato, which can propagate up to 100 times faster in the lab than in the soil. When a plant in a test tube has reached a certain size, it is cut into small segments, each of which contains a bud. The segments are, in turn, placed in test tubes. This painstaking task is carried out in a completely sterile environment. Not only does in vitro culture substantially facilitate the work of research teams by producing plant material in a short time, it also opens the door for the cultivation of exotic species that could then be marketed in Switzerland.

© Agroscope, Carole Parodi

Beyond national borders

While close cooperation between the Agroscope gene bank and local organisations is essential for the conservation of plant agricultural biodiversity, international partnerships also play a key role. Switzerland and 150 other countries adopted the Global Plan of Action for Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture, signalling their commitment to working together to conserve the world's crop plants. This commitment led to the construction of the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in the Norwegian permafrost. The facility, which has been called the Noah's Ark for plants, is a highly secure bunker stocked with samples from the world's gene banks, which regularly send duplicate seeds to the vault for preservation. The Agroscope gene bank has already deposited 10,422 seed accessions in Svalbard with a view to safeguarding Switzerland's plant genetic heritage.

© Agroscope, Michael Gysi

However, as Eric Droz points out, "there's no point conserving genetic resources if we can't identify them". Identifying stored samples is thus a major focus of international cooperation on the conservation of plant agricultural biodiversity. This requires some real detective work on the part of Eric and his European partners. "The type of analysis we use is also used for criminological and relationship tests. It involves comparing various data with data held by other laboratories," he explains. Scientists looking to map the genetic profiles of plant samples examine fragments of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) known as molecular markers, which indicate the degree of similarity between two plants. This enables them to identify samples that have been recorded under the wrong name and also reveals similarities between varieties with different names. For instance, it turns out that the potato variety known as 'Blaue Österreich' in Switzerland is called 'Bleue d’Auvergne' in France, 'Karjalan Musta' in Sweden and 'Skerry Blue' in Germany.