A brief (and thrilling) history of Swiss cinema

Swiss cinema is modest compared to the big guns in Hollywood, but it plays a crucial role in defining the country's identity. Join us for a look at some of the key films from each period.

In the beginning, all films screened in Switzerland were imported. The year was 1896, just a few months after the Lumière brothers invented the cinematograph, when photographer Maurice Andreossi installed a projector at the Alpineum in Geneva’s Rue du Vieux-Billard. The first Swiss feature-length film would only appear in 1917 with Eduard Bienz’s Der Bergfuhrer, which was also the first ‘mountain film’ – a genre which still continues today.

The growth of Swiss cinema continued with Bünzlis Großstadterlebnisse, the country’s first talking picture. Directed by Robert Wohlmuth, it tells the story of a serious man who applies for an acting job and suddenly finds himself neck deep in the amazing world of motion pictures.

Wars and mountains

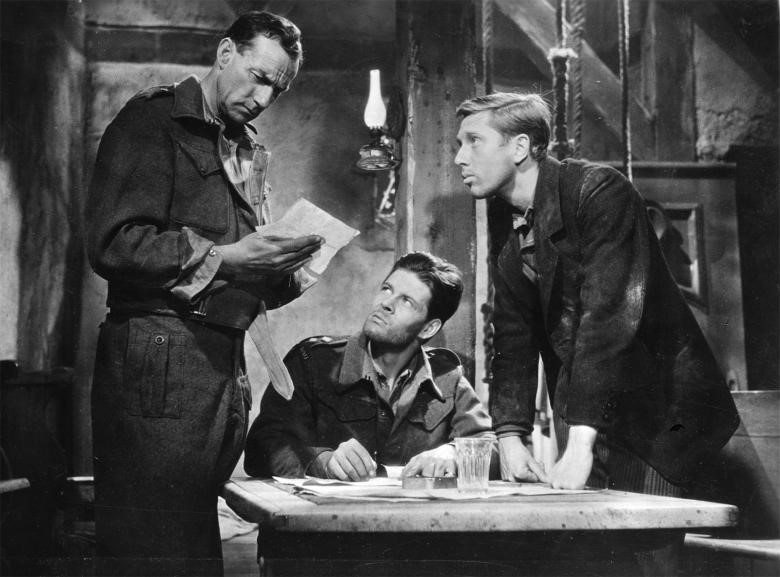

In 1937 the government began to heavily subsidise the cultural industries, and in the following years Swiss cinema experienced its first golden age, with works such as Fusilier Wipf (1939), Gilberte de Courgenay (1941) and Die Missbrauchten Liebesbriefe (1940). It was around this time that director Leopold Lindtberg achieved international recognition with Die letzte Chance (1945). This film, about a group of refugees fleeing the Second World War, took the top prize at the Cannes Film Festival and won a Golden Globe in the United States.

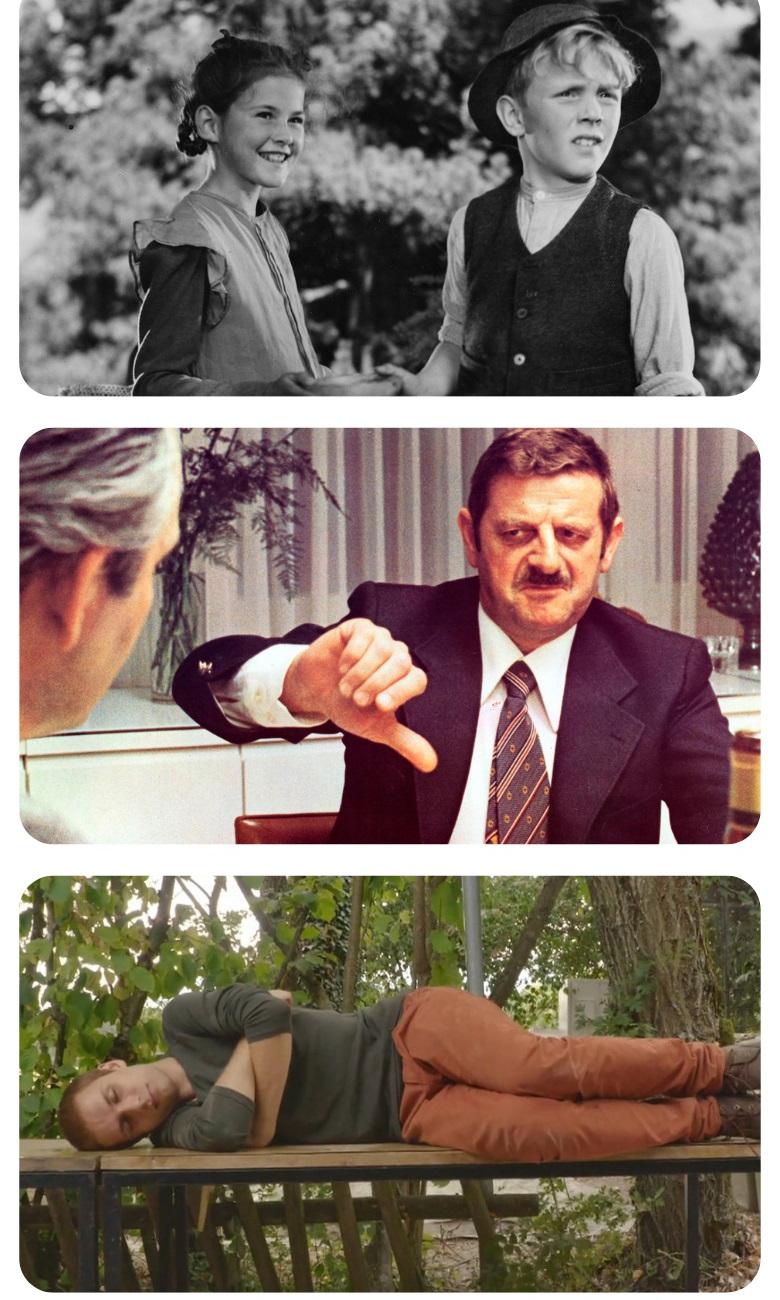

A sort of ‘return to the roots’ took place the following decade, when Luigi Comencini released Heidi (1952), a hugely popular film set in the Alps. Based on the children's book by Swiss author Johanna Spyri, Heidi sold more than 550,000 tickets in Switzerland, and a further million in Germany. Its sequel, Heidi and Peter (1955) was the first full-colour Swiss film.

The New Wave

In the mid-1950s, inspired by the French Nouvelle Vague (led, among others, by French-Swiss director Jean-Luc Godard), a group of young directors began to make films with a more dynamic and experimental visual style. The ‘Groupe 5’ from Geneva – consisting of Alain Tanner, Claude Goretta, Michel Soutter, Jean-Louis Roy and Jean-Jacques Lagrange – developed an interesting collaboration scheme involving the sharing of actors and composers. “In Switzerland, there were no film schools. Directors were often self-taught or learned their craft abroad,” explains Ivo Kummer, head of Cinema at the Federal Office of Culture.

From this period are Tschechow ou le miroir des vies perdues (1965), A propos d’Elvire (1965) and Charles mort ou vif (1970). The latter tells the story of a man in his fifties who runs a small Swiss watch factory and one day realises that he has wasted his life because he is not interested in the trade.

Commercial and international success

From the late 1970s Swiss cinema entered a period of ups and downs, which nevertheless included some major milestones. In 1978, the Swiss comedy Die Schweizermacher, directed by Rolf Lyssy, became a huge box-office success, reaching over a million admissions in Switzerland alone. In 1981, a Swiss-Austrian-German co-production named Das Boot ist voll (The boat is full) bravely tackled the country's restrictive asylum policy during the Second World War. Directed by Markus Imhoof, it was nominated for an Oscar for Best Foreign Film and is still considered one of the classics of Swiss film.

In 1990, the drama Reise der Hoffnung (Journey of Hope) by acclaimed filmmaker Xavier Koller became the first – and so far only – Swiss film to win an Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film.

Documentary film gems

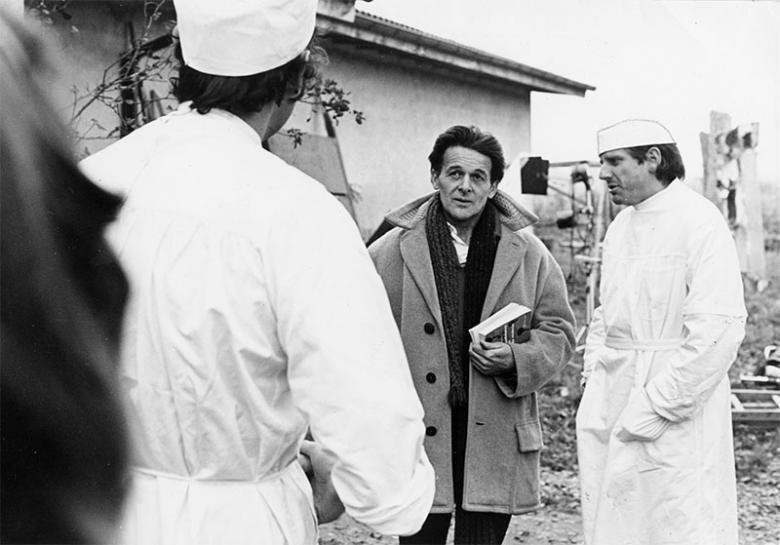

For many years the Locarno Film Festival has offered a large space for documentary films, an area where great Swiss directors such as Zurich-born Richard Dindo have shone. In The Execution of the Traitor Ernst S. (1976), Dindo and his collaborator Niklaus Meienberg dealt with the shooting of an alleged Nazi agent in the 1940s, a subject that generated controversy both in Switzerland and abroad. Another popular Swiss documentary was Mani Matter - Warum syt dir so truurig? (2002) by Friederich Kappeler, based on the life of the singer-songwriter and poet Mani Matter, which attracted over 140,000 viewers, a very high figure for a work of this genre.

In the same vein, Markus Imhoof’s More than Honey (2012), a film that explores the alarming, worldwide disappearance of bees, should not be overlooked. It premiered at several festivals and became the most successful Swiss documentary of all time.

The Future

Ursula Meier’s Sister (2012) is perhaps the most accomplished example of the new Swiss cinema, telling in a rough yet daring style the hard life of a young boy and his older sister in a village in the foothills of the mountains. The following year Lionel Baier’s Les grandes ondes (à l'ouest) showed a more relaxed style and a certain indie flair, a film about a Swiss state radio team that gets involved in the Carnation Revolution in Portugal.

More recently, directors Sergio Da Costa and Maya Kosa released Bird Island (2019), a film halfway between documentary and fiction nominated for the Golden Leopard at the Locarno Film Festival.

The coronavirus pandemic put a brake on the film industry. While cinemas remained closed, more and more users switched to watching Swiss films via online platforms such as Cinefile, Filmingo or Artfilm. This forced pause is perhaps the perfect opportunity to catch up and get to know the rich history of Swiss cinema.

Sources: SWISS FILMS, ProCinema, Switzerland Tourism, Swissinfo

More information on Swiss films:

• SWISSFILMS

• Cinémathèque suisse

• Calendar of Swiss film releases abroad