Wild hay making – a fascinating Swiss tradition

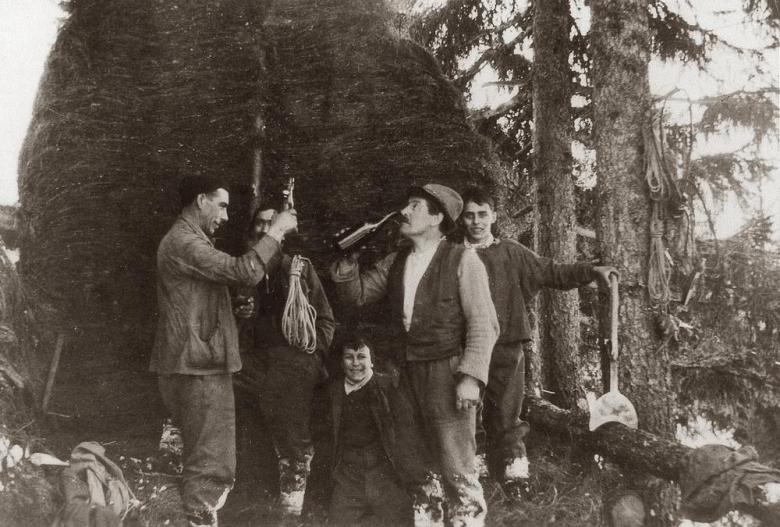

In my family archives, I have come across a black and white reel dating back to the 1960s. The film documents my ancestors on a late summer day as they collect fresh hay off their pasture in the Rhine Valley. At one point, an elderly farmer loads a huge ball of hay onto a sledge in order to haul it to the valley. These scenes got me thinking: what is the tradition of alpine hay making all about, and is it still being practiced in this day and age?

The real Swiss supermen

For centuries, farmers in alpine regions have made superhuman efforts in order to harvest hay from the most remote spots in the mountains. Every summer, they would climb from the deep valleys to their pastures high up in the Alps to manually cut grass for hay production. Thanks to its nutritional value, this ‘fancy’ hay was used as animal feed during the long, cold winters.

But let’s rewind to the beginning of the hay production cycle. The process involves several stages and starts in early summer. The first task after the snow has melted is to inspect alpine pastures for rocks, branches and other debris which has collected there during winter. After any obstacles have been removed, farmers have to establish access paths and level out any eroded patches.

Right around July, it is time for the next task. With scythes in hand and secured by climbing irons and ropes, farmers and their seasonal laborers will move along the near vertical pastures to cut grasses, herbs and shrubs. Despite the fact that technology has evolved over the years (farmers now wear mountaineering shoes instead of wooden shoes with makeshift spikes), the basic challenge has remained the same: how to move about safely on the vertical hillsides.

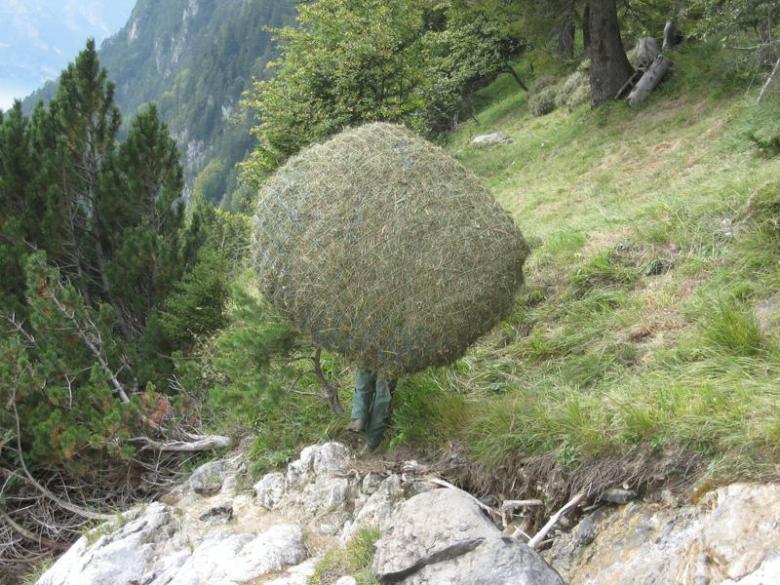

In late summer, it is time to harvest. Now that the organic matter has been slowly dried by the sun and the wind, farmers will once again return to their patch in the mountains. Using large rakes, they will gather the dried wild hay into piles, then stuff it into oversized nets weighing up to 60 kg each.

The nets, which farmers call Pinggel, used to be loaded onto sledges for transportation to the valley. Today, a common strategy in hay ball logistics is the zip line. In the canton of Uri with its steep cliffs, the whistling sound of flying hay nets can often be heard from afar. However, helicopters are the most efficient mode of transport for Pinggel – moving up to 1000kg of hay per minute.

A risky endeavour

The last stage of wild hay making is also when most accidents occur. After all, handling the bulky, heavy hay at great heights is extremely hazardous. People involved in this risky tradition must be strong and agile, and have advanced mountaineering skills. A century ago, the inventive Swiss farmers figured out the perfect diet to get them through the summer. According to Alois Blättler, a well-known haymaker of his time, the beverage of choice was heavily sweetened black coffee spiked with shot of liquor. Farmers’ meals consisted of “bacon, smoked sausages, beef jerky, bread and cheese.” (Alois Blättler, 1944)

But why would alpine farmers go to the trouble of harvesting grass in every nook and cranny?

Apart from the high nutritional value of wild hay compared with industrial feed, there are some less obvious reasons for alpine hay making. Take avalanche prevention. Snow masses naturally gain momentum on slippery surfaces. If the pastures were left untended during summer, the autumn rain and winter snow would flatten the high grass, facilitating erosion in the spring.

Another tremendous benefit of practicing wild hay making is the health of Switzerland’s plants and animals. These vertical pastures are left untouched for most of the year, meaning a great number of insects and wild flowers have space to flourish. Butterflies and wild bees are busy collecting nectar, while caterpillars and other critters enjoy nibbling on juicy plants. Pastures designated for wild hay harvesting are true havens for biodiversity.

Haying makes a comeback in the canton of Uri

Do you remember the last time you hiked across a pasture in late summer? Did you smell the nostalgic scent of fresh hay? There is a good chance you did, since alpine haying in has enjoyed something of a revival in recent years.

With advances in farming technology and a lack of financial incentives, this centuries-old tradition was on its deathbed when Uri’s local authorities launched a heritage initiative in 2013 in a renewed effort to save this important activity. The initiative included special subsidies for farmers who tend to the pastures by hand, and for those who maintain pieces of land designated ‘difficult to access’.

More than 100 farmers have since jumped on the hay wagon, and this small canton now boasts one third of all wild hay pastures in Switzerland. About two dozen spots are located on Mount Rophaien and in Isenthal where wild hay making is a true living tradition. In fact, thanks to these continued efforts, the expanses of wild hay were named Swiss Landscape of the Year 2016.

Where can alpine hay making still be witnessed in Switzerland?

Those fascinated by history and traditions can experience wild hay making in several regions. If you hear the sound of leaf blowers in the mountains, reassure yourself with the thought that modern day hay making is in progress. The key is to climb above 1,500 meters in altitude to any of these hay making hot spots:

- Bernese Oberland: Niesenflanke, Brienzer Grat, Saanenland, Kandertal

- Glarus: Brandalp (Ennenda), Bischoff (Elm), Glattalp (Engi), Ahornen (Näfels)

- Graubünden: Avers, Hinterrhein, Rheinwald

- Obwalden: Stanserhorn, Pilatus, Sachseln, Lungern, Engelberg

- Nidwalden: Stanserhorn, Buochserhorn, Oberrickenbach, Haldigrat above Niederrickenbach

- Schwyz: Fronalpstock, Muotathal

- Ticino: Monte Generoso, Arogno

- Uri: Rophaien (Flüelen)

Swiss German glossary of wild hay making terms

Dengeln/Dängelen {verb}: to sharpen a scythe

Mähen {verb}: the efficient cutting of grass with a scythe. Cutting grass in a clean sweep of the scythe that leaves no clumps behind is a skill that takes a lifetime to learn. It is best done when the ground is still moist with dew.

Pinggel {noun}: huge ball of dried wild hay stuffed into an oversized net

Planggen {noun}: near vertical pastures that are too steep to graze cattle but are perfect for sheep and goats – and for harvesting wild hay

Triste {noun}: a traditional method for stockpiling wild hay in the open. A tree trunk, surrounded by a bed of rocks and twigs, serves as the center of gravity. Hay is piled around the trunk in such a way that it is stabilised by its own weight.

Wildi {noun}: a wild hay meadow

More information