The way to modern direct democracy in Switzerland

When it comes to political co-determination by citizens, Switzerland is the undisputed world champion. More than one third of all referendums ever held at national level worldwide have taken place in Switzerland. The historical origins of direct democracy in Switzerland are just as interesting as the continuing topical nature of citizens' rights themselves. We provide below an overview.

Recently there has been a growing trend for referendums on a broad range of issues: in places as varied as Catalonia, Australia, California, Berlin, the United Kingdom and Turkey, referendums have recently taken place, more often than not arousing a high degree of controversy. The direction of travel is clear: in addition to electing representatives to govern in presidential palaces and parliament buildings on their behalf, voters are increasingly being asked to take a position on concrete proposals at the ballot box. But it is not only the issues being voted on that give rise to such heated public debate – the rules of voting too are a source of much disagreement.

According to Uruguayan political scientist David Altman, one of the world's leading experts on direct democracy, this is not surprising: "Direct democratic decision-making processes ultimately result in an additional and finer distribution of power. Those who already have great decision-making powers in a political system are usually opposed to the introduction of direct-democracy processes such as the popular initiative and the referendum." This was also the case in Switzerland, the small federal state in the heart of Europe, which today has the world's most comprehensive set of instruments and the most experience, with David Altman describing it as the 'gold standard for direct democracy'. In view of the global trend towards more direct democracy, Switzerland serves as a role model time and again, and its experience is used as a reference. For a meaningful comparison it is important to consider the historical roots and their development over time up until now.

The French Revolution: the cradle of modern direct democracy

When modern Switzerland was founded in 1848 after a brief civil war between Protestant and Catholic cantons, the Federal Constitution knew neither the popular initiative nor the referendum.

The invention of modern direct democracy, i.e. the right of citizens to participate in the political decision-making process and to have the final say, dates back to the French Revolution: here, after the deposition of the king in 1792, the Enlightenment philosopher and revolutionary Marquis de Condorcet was elected rapporteur of a national constitutional convention. There he enshrined not only the 'controlling' mandatory constitutional referendum, but also the 'progressive' citizens' right of initiative.

But already in 1794 Condorcet fell victim to the turmoil of the revolution and under France’s current centralist political system, only the presidential plebiscite remains, reserved for the ruling elites. What failed in France found fertile ground in its decentralised eastern neighbour, Switzerland: from 1830, citizens' rights were incorporated into the constitutions of almost all cantons of the Confederation before they were introduced at federal level. In addition to the decentralisation of Switzerland, another aspect also contributed to direct democracy gaining a foothold in Switzerland faster than elsewhere, gradually being introduced at all levels of government: assembly democracy. This original form of direct democracy developed in ancient Athens more than 2,500 years ago and was already practised in many Swiss towns and cantons in the Middle Ages. It still exists today in the form of communal assemblies and in the cantons of Glarus and Appenzell Innerrhoden as the Landsgemeinde.

The Landsgemeinde as a pre-modern form of direct democracy

The highly symbolic and powerful image of the Landsgemeinde, with several thousand citizens raising their hand to vote, can sometimes lead observers from elsewhere in Switzerland and from abroad to reduce direct democracy to this pre-modern practice, in which voting secrecy is virtually non-existent. In fact, the political strengths of direct-democratic citizens' rights are brought to bear in a much more contemporary context, which has little to do with the direct assembly type of democracy, which is strictly limited in time and space.

With corresponding reforms at cantonal level, citizens' rights in Switzerland at the federal level have been gradually expanded, refined and modernised over the past 150 years. For example, the referendum was incorporated into the Federal Constitution in 1874 as a control instrument for parliamentary laws, and the right to constitutional initiatives by the people was added in 1891. In the course of the 20th century other provisions were added, such as for referendums on international treaties – in 1921 – and the possibility of voting on variants. The latter consists in the government and parliament of Switzerland being able to present a counterproposal to the specific concerns of a popular initiative. In this case, the electorate can vote YES to both proposals (possible since 1987) and then indicate in a deciding question which variant they would prefer in the event that both proposals are adopted. This enhanced form of voting demonstrates clearly that the focus of Switzerland's direct democracy is on compromise-oriented dialogue between citizens and authorities, and not on stubborn confrontation.

Fierce struggle for (direct) democracy

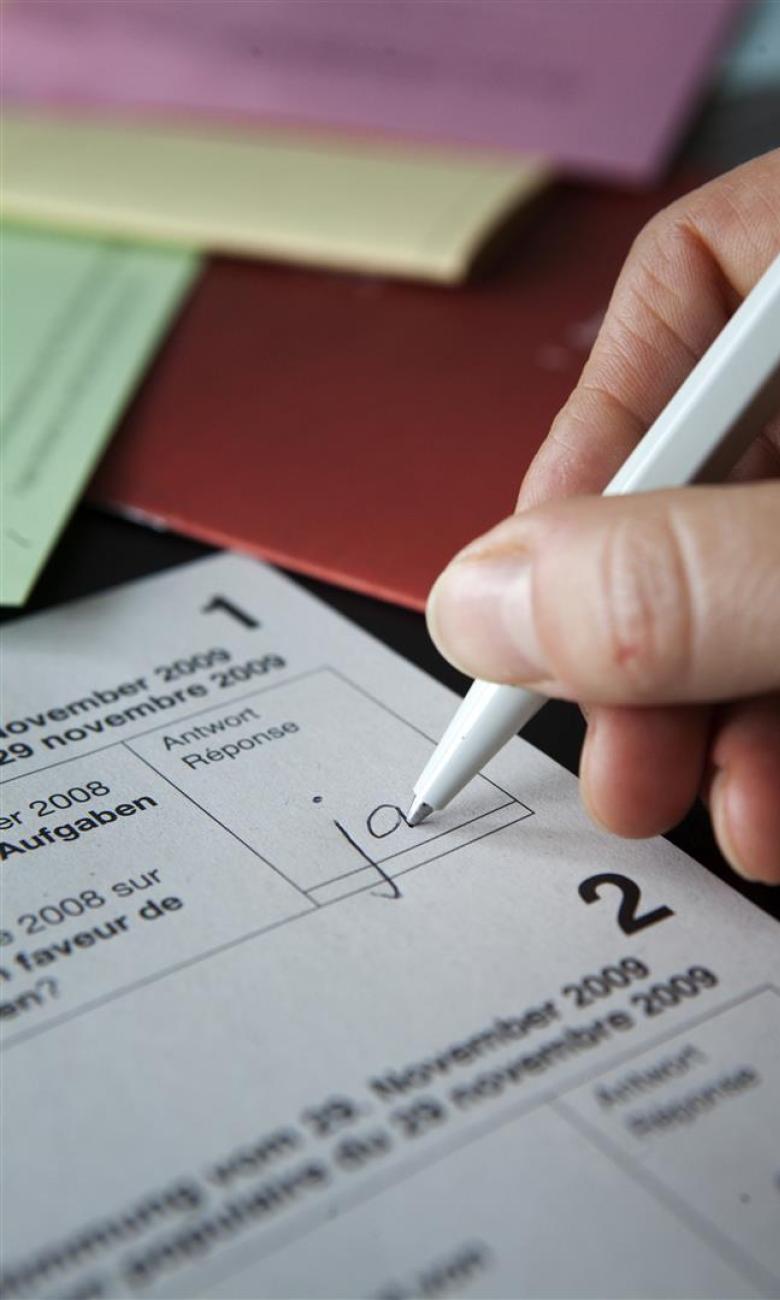

The ways in which citizens in Switzerland can take part in referendums today is also modern: voting is thus possible a few weeks before the actual polling day. Today, more than 90 per cent of all votes are cast by post or electronically via the internet. The few remaining polling stations therefore usually look quite empty on polling day. Despite the remarkable pro-democracy development seen since the founding of the federal state almost 170 years ago, it should be noted that many reforms in Switzerland too initially encountered resistance from those in power. This is painfully illustrated by the introduction of the general right to vote for men and women: while Swiss men of legal age (with restrictions until 1915) were allowed to have a say in the country from the outset, Swiss women had to wait until 1971 for this right – much longer than in most other modern democracies of the world. It also took several attempts at the ballot box to reduce the voting age to 18 today. Often, not only the majority of those already entitled to vote were sceptical about extending voting rights to other persons, but also the elected national parliament in Bern. After the suspension of citizens' rights during the Second World War, a majority of the people's representatives spoke out against the reintroduction of direct democracy. For this reason, engaged citizens launched the popular initiative for a return to direct democracy in 1946, which was finally voted on three years later, on 11 September 1949. Just 50.7 per cent of the electorate voted in favour of this proposal which was so important for the further course of history.

A vast wealth of experience

These examples demonstrate clearly that direct democracy is not a matter of course, even in Switzerland, the world champion of citizens' rights. On the contrary, even in this small country of over 8.5 million inhabitants, implementing the right to direct political participation, which is also enshrined in Article 21 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948, is constantly being disputed. In Switzerland, as in many other countries of the world, the focus is less on whether than on how people's rights are to be respected. This is particularly evident in the fact that today the majority of states around the world have forms of direct democracy in their constitutions, and since 1980 in eight out of ten states around the globe there have been referendums on substantive issues. In view of this rapid expansion and the associated initial teething troubles, Switzerland's vast experience has become an important source of information and inspiration for democracies all over the world.