The captivating delights of Swiss mechanical engineering

Though closely related to watchmaking, Swiss music boxes and automated dolls are still less well known than Switzerland's famous watches. And yet their inner workings are just as complex - sometimes even more so…

Switzerland's watchmaking tradition long encouraged the development of expertise that combines technical skill and art. In the 18th century, inventors started using high-precision mechanics to power automata, music boxes and singing bird boxes - captivating anyone who saw them.

Their elegance has not lost any of its poetic charm and still enchants onlookers today – even in this age of electronic devices and robotics. Human-shaped mechanical devices blink their eyes to better convey the illusion of being alive, while delightful little birds plump their feathers and sing a lilting tune. These objects were designed to last. Indeed, they have endured for centuries, their mechanisms still running smoothly and never seizing up. Some are even still being made in Switzerland today, with their makers following in the same tradition.

Swiss invention: the cylinder music box

The 18th century saw a fad for clockwork mechanisms, especially in Geneva. One such mechanism was put to use in a new type of device: the cylinder music box, invented in 1796 by Antoine Favre of Geneva. First used in watches, jewellery and snuffboxes, the system proved a great success when installed inside a standalone box designed to be displayed in sitting rooms.

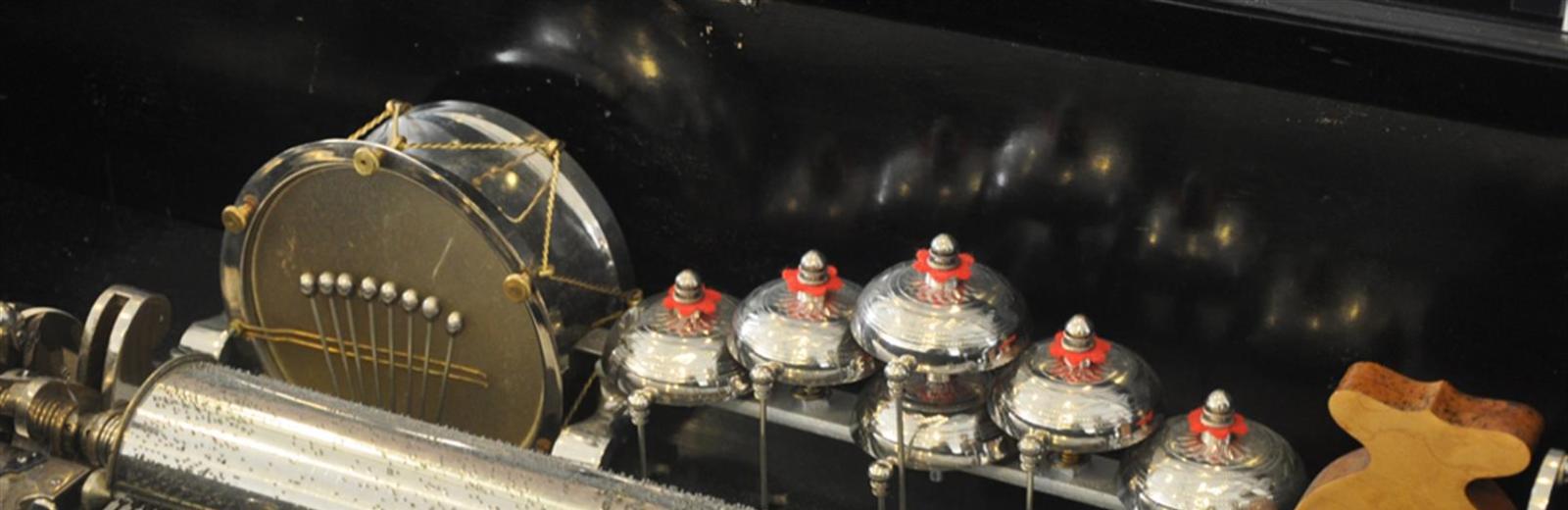

As innovation progressed, music boxes became increasingly complex. They could play multiple tunes and were augmented with bells and castanets - even the sounds of an accordion or mandolin. This fascinating story is told at the Centre International de la Mécanique d'Art (CIMA) in Sainte-Croix, Switzerland. Visitors can marvel at all the mechanisms, some of which have been working for two hundred years. And the location is significant too. This village in the Jura was a hotspot for the manufacture of mechanical devices in the 19th century, at one time home to up to 40 specialist firms. Since then, most of them have disappeared with the advent of electronics.

Singing bird boxes: pure delight!

Appearing as if by magic: once you rewind the mechanism the box opens to let a bird emerge. It bursts into melodious singing, accompanied by flapping wings and its beak gently pecking. And once the song is finished it disappears back into its box!

It's almost impossible not to be captivated by these mechanical birds, so one can only imagine the impact they made when first invented in 1780! They emerged from the imagination of Pierre Jaquet-Droz, a mechanic and watchmaker from the mountains of Neuchâtel.

Initially, the birds were installed in cages and their singing was created using a bellows to propel air into a piston. The system would later be further developed by Blaise Bontems, a French watchmaker. He began producing singing bird boxes in Paris in 1848 and was the one who first placed the bird in a snuffbox at the request of Napoleon III. More than a century later, the mechanical birds migrated back to their home country when the Manufacture Reuge acquired the Bontems company and Germany's Eschle, another leader in the field.

An extremely complex micro-mechanism

Today, the singing bird boxes are designed at Sainte-Croix, using the same techniques as in times gone by. A Reuge bird has 214 parts and requires the expertise of a master watchmaker to be assembled. Birds from Frères Rochat boast the most complex micro-mechanisms of all. It takes six months to assemble all 1,227 parts. These clever mechanisms were rediscovered a few years ago, after two centuries of oblivion. Worth up to several hundred thousand euros, these pieces are sold to collectors in the know around the world.

Automata, a dying art

Master mechanics also dream of reproducing human movement. They use the same principles as music boxes, except that the cog-driven shafts in this case activate the movements of the automata. When at rest, they look like dolls in a collection - but they are brought to life by the magic of cogs. During their show, they might raise an arm or leg, blink their eyes and move their lips. In those days, they were a wonder - and they still captivate today.

A trio of celebrated automata from Neuchâtel

Among celebrated Swiss automata there is a trio that must absolutely be seen at the Musée d'Art et d'Histoire de Neuchâtel. The Writer, the Draughtsman and the Musician were designed at La Chaux-de-Fonds between 1768 and 1774 by Pierre Jaquet-Droz, his son Henri-Louis and Jean-Frédéric Leschot.

Each automaton comprises several thousand parts. The Writer can write a pre-programmed text. He dips his quill in an inkpot and shakes it gently before he starts writing on the paper. The Draughtsman draws with a pencil, carefully blowing away bits of dust from the lead, while the Musician plays an aria on a miniature piano.

In their day, these sophisticated creations enjoyed worldwide fame. Huge crowds flocked to see them at public exhibitions. They travelled around Europe and even stopped in at the court of Louis XVI in 1775. In the late 18th century, their success was such that the Maison Jaquet-Droz had multiple workshops – in La Chaux-de-Fonds, Geneva and also London – according to the special edition of Art+Architecture en Suisse magazine devoted to mechanical objects.

Automaton maker: a rare art indeed

Making an automaton involves microscopic mechanisms as well as designing the object and clothing for it. At his workshop in Sainte-Croix, automaton maker François Junod keeps the art alive today. He studied the restoration of automata under Michel Bertrand, an artisan who is no longer with us today.

Together with his team, François Junod fills orders from around the world. His expertise in making and restoring antique automata is internationally recognised, for few men or women today have mastered the inner workings of this fascinating art...