International Geneva - a laboratory for the digital revolution in humanitarian aid

The fifteen international organisations as well as many NGOs located in Geneva are using technological advances to bring innovation to their processes and humanitarian missions. An overview of the latest technologies being used in humanitarian aid.

Innovation is thriving in humanitarian organisations. The major NGOs are undergoing unprecedented change thanks to the boom in new technology. These new tools are not only making it easier to coordinate operations; many victims are able to make hands-on use of the support systems, making them more efficient. The fifteen international organisations located in Geneva are also using know-how gained from start-ups to transform their processes and humanitarian missions.

Several of them have created innovation units that are working with the private economy. In 2007, UNICEF became the first organisation to introduce a team dedicated to innovation, followed by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (HCR) in 2012. Many other organisations have since followed suit or are about to, including the ICRC, Terre des hommes, Handicap International, and the World Food Programme.

To avoid any duplication and to encourage synergy, they launched the Global Humanitarian Lab in 2016. Thanks to the support of the Swiss and Australian governments, this innovation laboratory based in Geneva aims to maximise their efforts by pooling certain resources. All these innovations are the result of increasingly close cooperation with start-up businesses, Swiss institutions of higher education and research centres, following the example of CERN, the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL) and the University of Geneva, which organise humanitarian hackathons with local start-ups every year.

Ushahidi, crisis mapping pioneer

Patrick Meier, a Swiss expert on crisis mapping, was the first to bring NGOs into the Web 2.0 era. His website, Ushahidi , introduced the practice of web reporting by geolocalising the tweets, text messages and emails sent by civilians on the ground and then mapping them. It all started in 2011, at the height of the Arab Spring. There was not a single UN correspondent in Syria, or Libya, to report on the needs on the ground. Given the urgent nature of the situation and the disinformation orchestrated by Tripoli and Damascus, which at the time were denying NGOs access to their territory, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs in Geneva (OCHA) called on the services of Ushahidi.

Established by Patrick Meier, Ushahidi is a tracking and information exchange system. Ushahidi is free to use and runs on open source software. In 2011 it enabled Libyans - activists and journalists - to report via SMS, Twitter, email and social media on the situations they were witnessing. All this micro-information (bombings, victims, arrests, shortages of water and medicine) was then aggregated, geolocalised and mapped by Ushahidi.

The map generated by this information outlined the front line as pro-Gaddafi or rebel forces advanced and retreated, as well as showing refugee movements and destroyed roads. Once online, it provided a real-time account of the country’s acute crisis zones. In Web language, this is known as “crowdsourcing”, i.e. the compilation, visualisation and interpretation of thousands of pieces of data and reports from the internet.

The site was an instant success. At the time, the American magazine ‘Technology ¬Review’ classified the site among the 25 most innovative businesses of 2011, alongside Twitter, Facebook and Zynga. Today, Patrick Meier has become a leading light of humanitarian aid in the Web 2.0 era, masterminding almost all new technology in the field.

Lake Geneva’s drone valley at the service of humanitarian aid

The use of drones is a growing trend in the humanitarian sector. In 2014, the United Nations issued their first guidelines on the subject. In April 2015, when the earthquake struck Nepal, the Swiss NGO, Medair, based in Lausanne and specialising in emergency aid, used drones to measure the extent of the damage, determine which zones required the most urgent intervention and plan distributions to areas that had been cut off.

In Switzerland, a number of start-ups are developing specific products. One such company is Flyability, with its Gimball, which can enter collapsed or burning buildings and has already been put to work for NGOs. In future, this carbon ball could be used to assist earthquake rescue teams. This innovation won the company the first prize of a million dollars in 2015 in the ‘Drones for Good’ competition in Dubai.

At the start of 2016, Red Line, an EPFL Afrotech project, flew its first cargo drones in Africa. This first fleet of drones, which can each carry 10kg of cargo, brings medicine and blood supplies to the most remote regions.

Red Line’s drones have also made it possible to increase the number of HIV screening tests in Malawi by carrying tests between local health centres and rural zones. While the use of drones in disaster areas is growing rapidly (the market is set to be worth 1.2 billion dollars by 2020) it remains ambiguous and poorly regulated. In fact, in conflict zones, the humming of drones is often a signal to local populations of imminent air raids. The businesses developing drones for humanitarian response are, however, commercial entities whose products are destined for civilian use.

Health, security and electricity

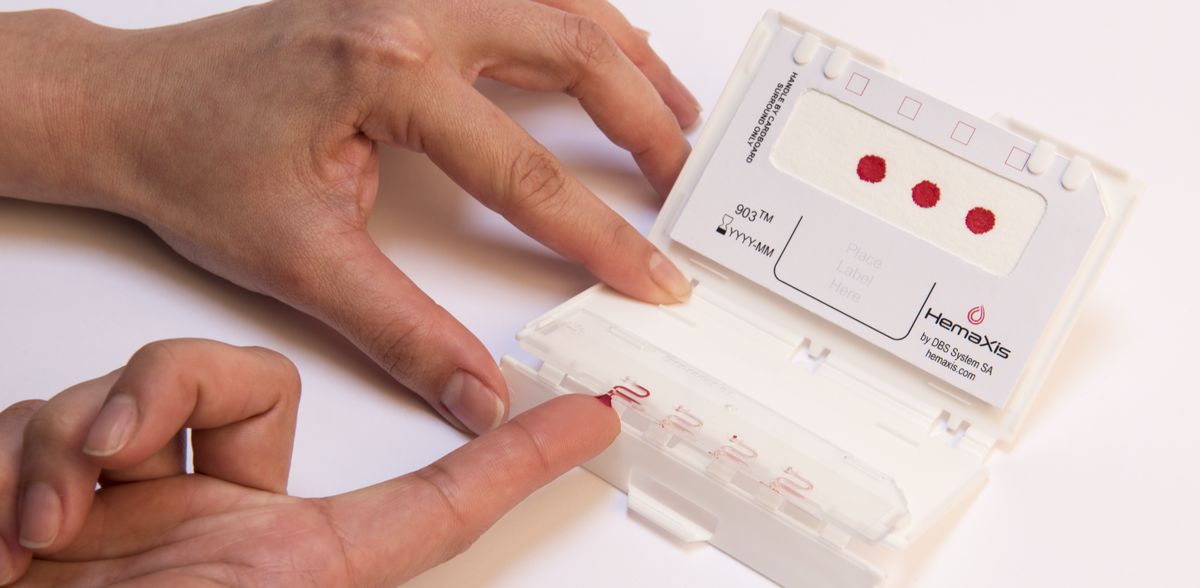

A growing number of Swiss start-ups are innovating in other humanitarian sectors. In Gland in the canton of Vaud, the fledgling DBS System raised CHF 2.5 million for its micro blood sampling system. The system is called Hemaxis and consists of a kit, not much larger than a business card that can replace traditional blood tests. Users just have to prick their finger using a lancet. The drop of blood is then placed on a plastic slide and by capillary action penetrates four microchannels feeding it towards a small sheet of absorbent paper. The blood dries and the kit is then sent by post to a laboratory for analysis. DBS System has already marketed the first generation of its system, which is used by laboratories, universities and NGOs.

In Geneva, a CERN research team has set up OhmPower. This energy solution aims to meet the electricity needs of refugees in camps. This very inexpensive system ensures the best allocation of electricity by prioritising essential services such as hospitals, schools and public administration buildings, while meeting the needs in individual shelters. With OhmPower, electricity can be provided from various sources. The research team is planning cooperation with the UN Refugee Agency.

It is one thing to take precautions when travelling but quite another to have precise details of the risks involved. This is precisely what the Geneva-based start-up SecuraXis is working on. Its goal? To provide NGOs with a real-time vision of a region’s security issues. Even today, it is still difficult to have a detailed, mapped overview of the dangers involved. SecuraXis provides humanitarian workers on the move in hostile regions with real-time security information that is geolocalised and mapped. It offers a unique approach to sharing information, online, in combination with security management tools.