Outer space: the Swiss women looking to the stars

Women took an interest in space long before the space agencies undertook to diversify their teams of astronauts. Three Swiss women with their feet firmly on the ground and their faces turned to the stars share what attracted them to the space sector.

States need to agree on their use of outer space

Natália Archinard has not been to space; a career in diplomacy was her gateway to outer space affairs. Deputy head of the Science, Transport and Space Section of the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, she leads the Swiss delegation to the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS). Achinard represents Switzerland in the multilateral negotiations held by COPUOS, which is responsible for promoting cooperation between states in the field of space and for resolving certain – monumental – challenges in a sector where newcomers are literally jostling for space and the strategic stakes are enormous. Until 30 April 2021, she is chairing the 58th session of the COPUOS Scientific and Technical Subcommittee. Space debris, heavy traffic in certain orbits, exploitation of space resources...there are quite a few issues to contend with.

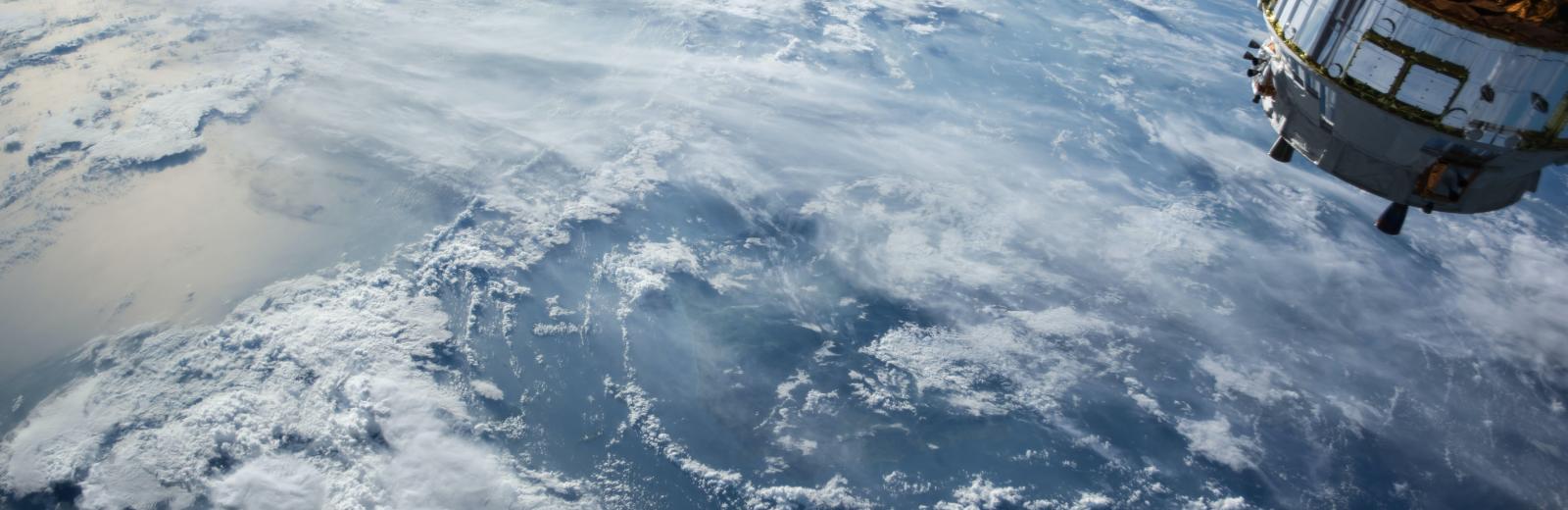

"The number of satellites launched in 2020 was almost double that of 2019," says Archinard. "Private companies such as SpaceX and OneWeb plan to launch thousands, or even tens of thousands, more. They already have authorisation from the relevant national authorities. But can orbits, especially near-Earth orbits, accommodate so many satellites without accident or interference if the traffic is unregulated? States need to coordinate and agree on their use of outer space, for example through common rules of conduct and standards – both to avoid accidents and to guarantee international security. Because a manoeuvre in space that is misinterpreted as act of aggression could well lead to conflict. That would be detrimental to everyone, including Switzerland. "

Our country does not have the capability to launch satellites, but it is a major contributor to the European Space Agency and certainly has its role to play. It is also satisfying to see that things are changing. When Achinard first joined the UN Committee in 2007, only three countries were represented by women. Now it is almost a third.

"As a child, I felt connected to the universe"

Muriel Richard-Noca's daily routine is a race against the clock. It would be an understatement to say that everything has been in a state of flux in Muriel Richard-Noca's life since ClearSpace – the start-up she co-founded – was chosen by the European Space Agency (ESA) to develop a brand new technology to clean up space. The stakes are high – the amount of debris in Earth's orbit is growing, as is the risk of collision.

Muriel Richard-Noca had her eureka moment in 2009 while working at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL) on the first 100% Swiss-made satellite, Swisscube, which was sent into orbit at an altitude of 700 km. A few months previously, a collision had smashed a Russian and an American satellite occupying this same orbit into over 2,000 pieces. "Swisscube was launched into this field of debris," she recalls. "So we set up a research programme with the aim of one day recovering our satellite." By the time ESA announced its call for tenders three years ago, several prototypes had already been developed by Muriel Richard-Noca's team, which stole the contract from under the nose of giants such as Airbus and Thales. Between the signing of the contract in November and the launch of its cleaning satellite, scheduled for 2025, the timing is particularly tight, admits the space engineer, who cut her teeth at NASA before joining EPFL and more recently assuming the role of company director. This has been "a humbling experience for me, who has always worked in academic set-ups", she admits. It is also an extraordinary experience, "because you have to found a company and develop a market from scratch".

Nothing like this has ever been done before. ClearSpace's satellite, which is still in the design phase, must be capable of approaching a chosen piece of debris and placing itself in orbit at the same speed – 28 000 km/h – in order to capture it using a shock-absorbent mechanical arm. This is a technological challenge since there is nothing to grab hold of on the spinning object.

Ultimately, ClearSpace's satellite is destined either to burn up in Earth's atmosphere along with its captured debris or to serve as a 'space tow truck' providing a commercial repair service for satellites that cannot be repaired from the ground. Exciting prospects for a woman who has been looking up at the stars since childhood!

"The space sector has something that is the stuff of dreams"

Aude Pugin is at the helm not of a space shuttle, but of a company with more than 400 employees, 350 of whom are based in Aigle in the Swiss canton of Vaud. APCO Technologies will equip the next European launcher, Ariane 6, with nose cones for the boosters and the attachments that link them to the main body of the rocket. This is a delicate operation, as the attachments must release to allow the launcher to take off. "It has to be absolutely perfect. If it doesn't uncouple, we'll have a serious problem," says Pugin. But it's worth the effort as working in such an innovative sector is extremely stimulating, she says. "Especially as it attracts young people, and more and more women. Several women work in our workshops, for example, on satellite equipment."

In the Pugin family, it was Aude's father André who first caught the space bug. It was he who founded the company and developed its space activities. His daughter did not immediately follow in his footsteps. After training as a lawyer, she joined the family business ten years ago, taking over in 2017. "I had the luxury of time to learn," says the multi-faceted entrepreneur, who also chairs the Vaud Chamber of Commerce and Industry and sits on the Federal Commission for Space Affairs. She takes us on a tour of her workshops and their 'clean rooms', designed to have low levels of contaminants. It is here that the structures housing electronic and optical components for the satellites are made. These are complex structures made of aluminium or carbon, both of which are light because every kilo sent into space is expensive and ultra-resistant in order to withstand the vibrations of a rocket launch and immense changes in temperature when exposed to the heat of the sun's radiation and the cold vacuum of space.

Ariane, ExoMars, Galileo... APCO has provided technologies to a large number of European Space Agency projects. Remember the Rosetta probe and its little robot Philae which landed on the comet Chury? "We helped to reduce the mass of an instrument made by the University of Bern," she says. "It's fantastic to think that we are building industrial equipment to be carried by a probe that will land on a comet in order to answer such incredible questions as the origin of life in our solar system."

Based in Switzerland, APCO Technologies has a branch at the Kourou launch base in French Guiana, where Pugin attended a rocket launch in 2018. "What impressed me the most, and I wasn't expecting it at all, is that alongside the roar of the launch, so much energy is unleashed that your whole body vibrates. The emotion is immense, and so is the physical sensation."

Curious to learn more about Switzerland as a space nation? Watch the video: