In search of Earth's sibling

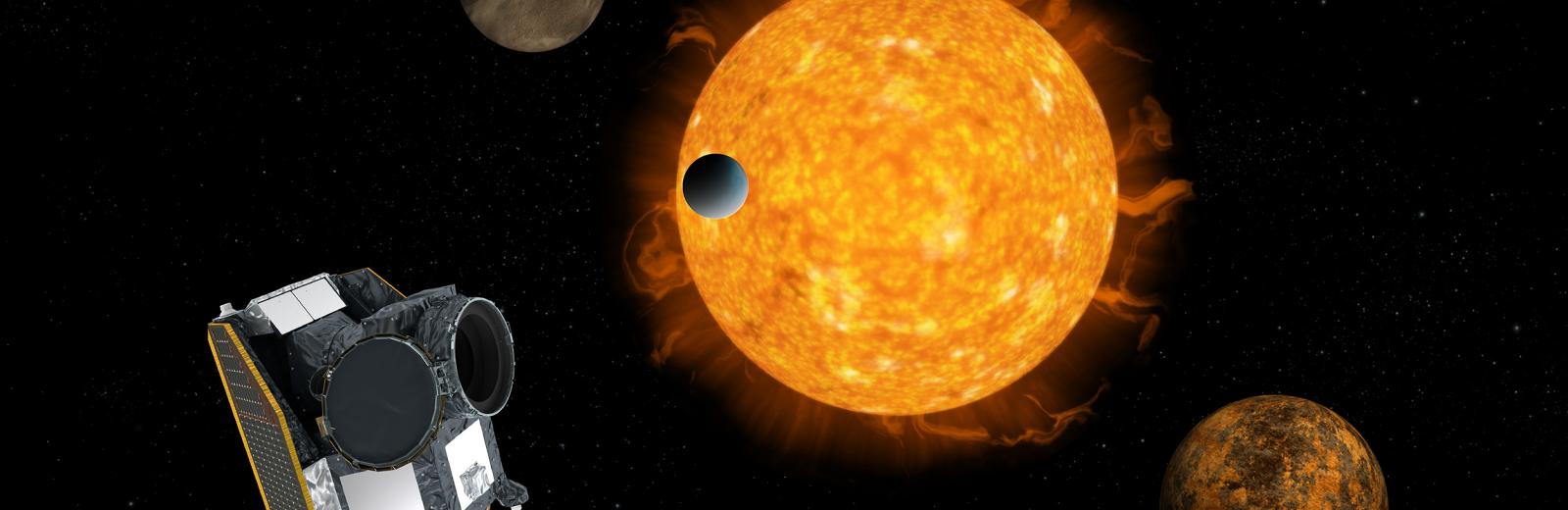

Switzerland is leading the consortium of 11 European countries participating in the CHEOPS mission. The CHEOPS telescope was launched in 2019 to learn more about the little-known world of exoplanets. This is the first mission Switzerland has led within the European Space Agency (ESA), although it has been a member since the agency's inception. Other missions are in the pipeline – more on that below.

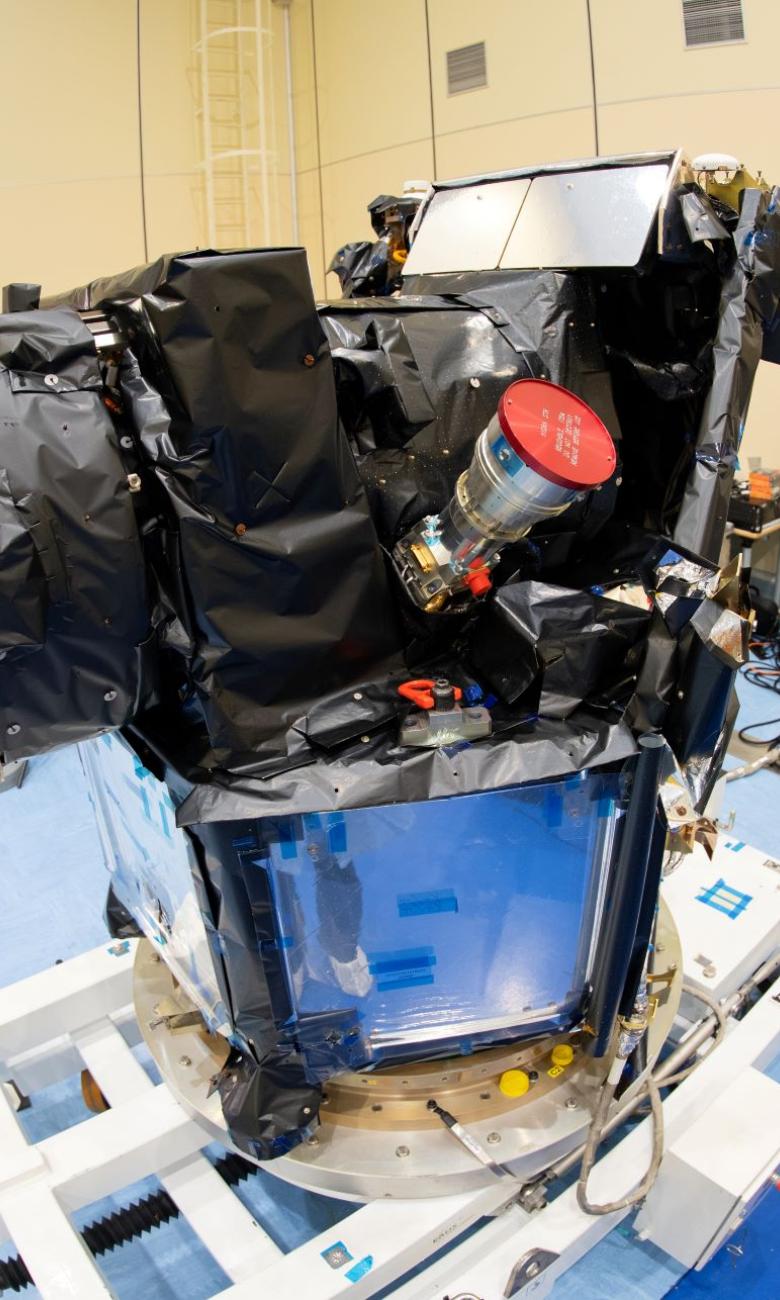

The European space mission CHEOPS will enable scientists to learn more about the extrasolar planets that have been discovered so far. Launched on 18 December 2019, the satellite orbits the earth at an altitude of about 700km in just over an hour and a half. The on-board telescope can scan about 70% of the sky, enabling it to meet the exoplanet characterisation objective set for the mission, hence the name CHEOPS (CHaracterising ExOPlanet Satellite). This high-precision instrument was designed and assembled at the University of Bern. It will enable us to measure the size of several hundred extrasolar planets and to better understand how they were formed.

Ultrahigh precision photometry

At the end of March 2020, scientists had completed the calibration of the space telescope. After successfully opening the instrument's cover and taking photographs, they passed the third crucial stage for the main three-and-a-half year mission. "We were overjoyed when we found that all systems worked as expected, or even better than expected," recalls Andrea Fortier of the University of Bern, who led the process of activating the telescope.

"The trickiest test was to measure the brightness of a star to an accuracy of 0.002% (20 millionths)," says Willy Benz, CHEOPS mission leader. This precision is necessary to discern the shadow cast by a planet the size of the earth as it passes in front of a star similar in size to the sun, using the transit method. From these measurements, scientists can deduce the diameter and composition of a planet.

At dawn and dusk, the satellite carrying the telescope flies over the Mission Operations Centre near Madrid, whose antennas are used to route data to the Science Operations Centre at the University of Geneva. There, the scientists collect and process the data and then issue the coordinates of the next stars to be targeted by the satellite. This is the very place where the winners of the 2019 Nobel Prize in Physics Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz paved the way for the discovery of exoplanets. Twenty-five years ago, the two professors discovered the first exoplanet, 51 Pegasi b, orbiting a star similar to our sun. They are now coordinating the observations of this mission under the aegis of ESA.

Switzerland in the driving seat

As a founding member of ESA, Switzerland has been actively involved since the organisation's inception and has taken part in almost all its missions. With CHEOPS, however, this is the first time Switzerland is in the driving seat. The University of Bern leads the consortium of scientists, engineers and technicians, who work for around 30 institutions from 11 European countries. ESA approved the mission in 2012 and launched the construction of the CHEOPS telescope five years later. Switzerland then took the lead on the first 'small' scientific project of ESA's Cosmic Vision programme, with a budget of around EUR 100 million, of which EUR 33 million was contributed by Switzerland.

Carrying on a tradition

Leading the CHEOPS mission is part of Switzerland's long tradition of involvement in space research. The aluminium sail created to capture solar wind particles had indeed made a lasting impression in 1969 during the Apollo 11 mission. Designed by the University of Bern and ETH Zurich, the sail was the only non-US experiment included in the module that landed on the moon. At that time, Switzerland was already a founding member of the European Space Research Organisation (ESRO) – a status it retained when ESA was formed as ESRO's successor in 1975. Since then, the University of Bern has successfully conducted around 30 space experiments.

The Swiss industrial sector has, for its part, put its expertise to good use, as in the case of RUAG Space (formerly Oerlikon Space), which supplies the fairings – or nose cones – of the European rockets Ariane and Vega. Start-ups are also making their mark, for example ClearSpace, which was appointed to head the European ADRIOS programme, responsible for actively removing waste from space. The EPFL spin-off has accepted the challenge of de-orbiting the Vega launcher's fairing by 2025, ensuring that it disintegrates smoothly as it re-enters the earth's atmosphere. To achieve this, ClearSpace is developing a satellite with several robotic arms designed to capture space junk.

Let us also not forget that Switzerland first ventured into space in 1992, when Claude Nicollier, an ESA astronaut from the canton of Vaud, embarked on his first of four missions aboard the Space Shuttle, which included space walks to repair the Hubble Space Telescope using a spectacular robotic arm.

Video: Preparations on the launch pad at Kourou in French Guiana and the launch of the Soyuz-Fregat rocket carrying CHEOPS. © ESA

International reach

With the CHEOPS mission, Switzerland is demonstrating its proficiency in pioneering new-generation satellites that are smaller, less expensive and more flexible in their use. Thanks to the extensive reach of its many universities, it can surround itself with the best international experts in their respective fields. "I've been part of this mission since day one and I have the opportunity to continue until its completion. It's a rare privilege. I want to make the most of this unique experience and learn how a mission evolves as it goes through its different phases," enthuses Argentine scientist Andrea Fortier, who has been fascinated by "the sky, its vastness and its mysteries" since she was a child. Major European space projects are now lining up at a steady pace. Among them, Switzerland is looking forward to participating in PLATO, a space observatory planned for 2026. Mounted on a platform, its 26 telescopes will allow us to observe a large part of the sky to detect all the planets capable of sustaining life elsewhere in the Milky Way.

Laurent Favre