Ursula Keller has seen the light at the end of the laser

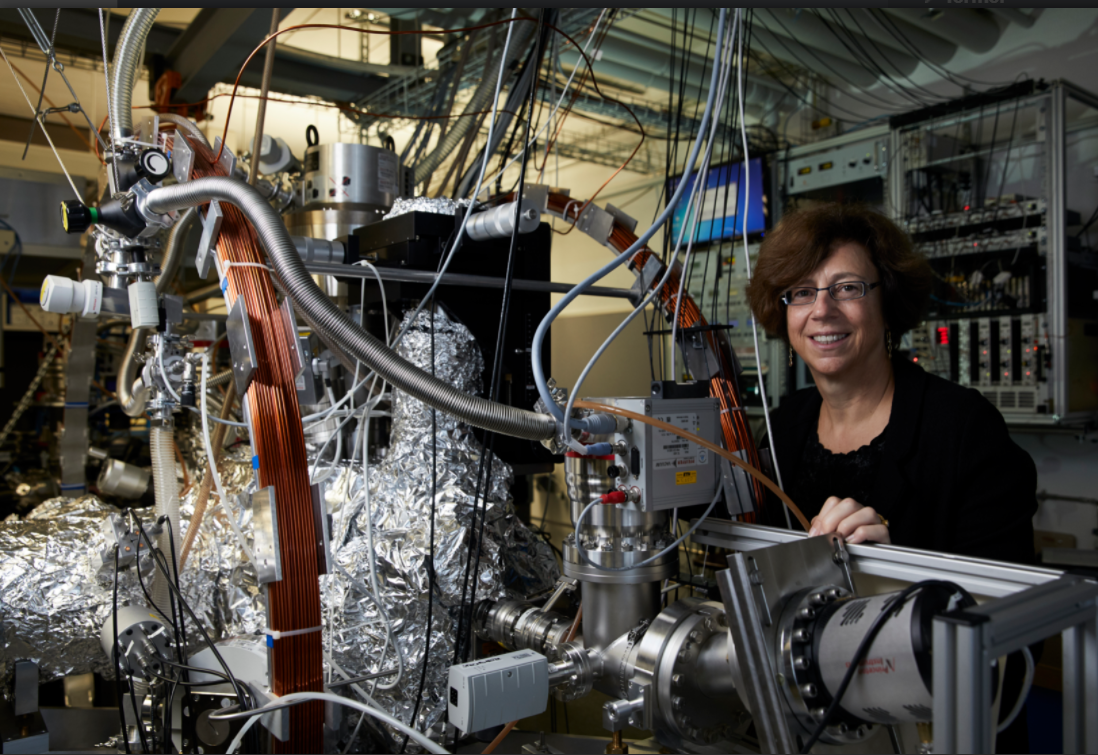

Ursula Keller, the well-known Swiss physicist, has more than one string to her bow: as the first woman to obtain a professorship in physics at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, this inventor specialised in ultra-fast laser technology won the 2018 European Inventor Award and was awarded a gold medal in 2020 by the international society for optics and photonics (SPIE). She is also committed to encouraging women to pursue careers in science or engineering.

Ursula Keller did not do very well at school, with the notable exception of mathematics and science. "Whether it was reading or writing, I got everything wrong. But looking back, I'm convinced that those poor results gave me an advantage. In rural, conservative Switzerland where I grew up, if a girl was good at all subjects, she was usually encouraged to pursue traditionally female occupations and certainly not technical subjects such as engineering ".

Lifetime achievement

If she had been good at school, Ursula Keller would probably not have become a physics undergraduate at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich at the start of the 1980s. She would certainly not have won the 2018 European Inventor Award either, awarded by the European Patents Office, nor a gold medal from the international society for optics and photonics (SPIE) in 2020.

These awards are the crowning achievement of an impressive career in which the renowned physicist literally revolutionised the use of laser technology, by developing, in the 1990s, the first method of producing ultrashort pulse lasers. This technique, known as SESAM, has since become standard in the electronics and car industries as well as in the fields of medical diagnosis and surgery. She was just 30 years old.

Natural curiosity

At that time, Ursula Keller was working in the United States at the prestigious AT&T Bell research centre in New Jersey, having recently obtained a PhD at Stanford University in 1989.

"Women in those fields were in a better position in America. Attitudes were more forward-thinking, and it was easier to get access to a laboratory. However, from the beginning it was made very clear to me that I would have to come up with something ground-breaking, and that worked".

So, with her fascination for laser technology, Ursula Keller tried to solve a problem that many engineers had grappled with in the past: "Since the invention of lasers, scientists had been interested in using this technology to transform materials. However, a continuous laser beam overheats the element to be modified and damages it". Keller then came up with the idea of using a semiconductor as a mirror and succeeded in producing pulsed light, making the laser a much more intense and precise tool. It is used particularly for soldering and cutting but also to carry out eye or brain surgery.

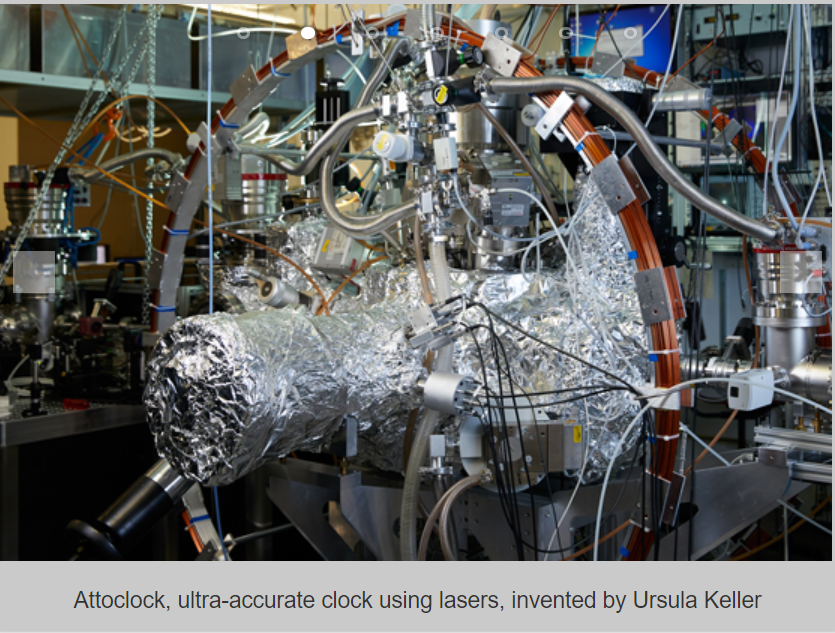

In her perpetual desire to find new purposes for the laser and driven by a strong interest in quantum physics, in 2010 Ursula Keller was also behind the Attoclock, the world's most accurate clock at that time, capable of measuring an attosecond, i.e. a billionth of a billionth of a second.

"My mind likes to explore, to come up against dead ends. The more questions that arise, the happier I am. I think I have always been like that. As a child I asked a great deal of questions and never took no for an answer. My parents must have had a hard time of it but I'm sure that this natural curiosity is what makes a good researcher ".

Underestimated difficulty

Ursula Keller's discoveries swiftly created a sensation in the scientific community. In 1993, she was appointed professor of physics at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich (ETH).

At the age of only 33, she became the first woman to hold a scientific professorship at the institution, not without encountering some hurdles: "The president at the time, Jakob Nüesch, made great efforts to appoint more women. The ETH did have, for example, a few female professors of architecture or pharmacy, but I was the first in the 'hard' sciences. In fact, I had completely underestimated what it meant to enter an all-male environment. It was very difficult because, for instance, important information was only discussed in 'insider clubs', from which women were excluded".

Shaping the future together

Keller refuses to divulge more about her personal history, as for the time being her combat is at a completely different level. Founder and president of the ETH Women Professors Forum, Keller is also mother to two boys aged 19 and 21. She is actively engaged in encouraging women to pursue careers in science or engineering, to bring about far-reaching institutional change.

"My dream is to increase the proportion of female professors at the ETH to at least 30%, and I'm sure that the 10% of women currently holding such positions will help us to achieve this goal. We have to support one another and work hard to bring about change, to avoid leaving physics, or any other scientific discipline, solely in the hands of men. We must be able to shape our future together and in equal measure. ".

This article originally appeared in 'Le Temps', by Sylvie Logean, April 2018