The catacombs of Valais: as fascinating as those of Paris

You don't have descend into the catacombs of Paris to feel the gaze of thousands of empty eye sockets. With its 24,000 skulls, the charnel house in Leuk in the Upper Valais region of Switzerland provides an equally chilling spectacle.

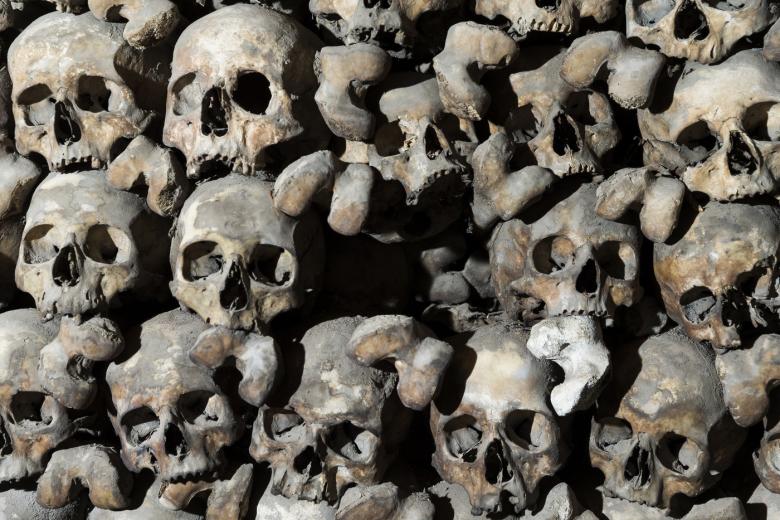

The moment you go through the door, death greets you with a toothless grin. As you look around the room, thousands of broken, jawless skulls stare back. In the centre, a Gothic Christ bleeds in large, motionless drops. The dead, stacked this way for centuries, contemplate his stigmata as if waiting for the resurrection. On the facing wall is a series of dance-of-death paintings. Clearly the grim reaper has a message for you: "I am Death, and I carry away young and old." You have entered Leuk charnel house in the Upper Valais, where 24,000 skulls contemplate eternity.

Cover image: The charnel house in Leuk, June 2018 – © Cyril Zingaro for Le Temps

All equal before death

"There are two main explanations for these macabre walls," explains Roger Mathieu-Uttenthal, chairman of Leuk parish council and charnel house guide. "One very basic reason was the lack of space. Let's go back in time to 1500. Leuk is the main church of a district of the same name. The population of its 12 communes go there to mark the seasons of Catholic life in the Valais of the late Middle Ages. Baptism, communion, marriage. And burial, of course."

But plots in the small cemetery were expensive, so they were reused. The deceased spent twenty-five years in the ground, after which their skulls were stored in the chapel, built in 1505. "We date the ossuary to that year," says our guide, "because that is the only verifiable information we have. They would have started stacking skulls earlier, but no one knows when." The Valais has 20 or so catacombs. Another of them is in Naters, 30 kilometres to the east.

© Cyril Zingaro for Le Temps

The second reason is religious," says Roger Mathieu-Uttenthal. "Imagine the rural Valais of the 16th century, where people could neither read nor write. The church wanted to show parishioners that there was justice in the afterlife. Man, woman, rich or poor: we all die in the end. In the wall, the skulls of the wealthy are indistinguishable from those of the poor." The nobility were not exactly subject to this ideal, he admits. They could choose to remain in the ground and not join the stack of skulls in the wall. Justice is all well and good, but what's the point in having blue blood if you're going to end up in a pauper's grave?

The dead of the French invasion of Switzerland

Over three centuries, the wall grew to nearly 20 metres long, 2.4 metres high and 3 metres wide. Its 24,000 occupants are anonymous, many of them simple farmers. Others bear scars that speak of a violent death, such as holes in the back of the head.

Probably bullet wounds.

Roger Mathieu-Uttenthal

Valais has not always been a peaceful place. After the French Revolution, the French attacked and defeated Austria, creating the balance of power necessary for Swiss independence. The Swiss found themselves at the mercy of the French, who invaded and proclaimed the Helvetic Republic (1798–1803).

© Cyril Zingaro for Le Temps

Valais was not spared. The French freed the French-speakers of the Lower Valais from subjugation to their German-speaking Upper Valais neighbours and declared every man from the age of 20 to 45 years eligible for conscription. The pious inhabitants of Upper Valais preferred to fall on the battlefield than to serve the 'enemies of the faith'. The badly-equipped mountain soldiers were no match for the French revolutionary troops, however, and were defeated in May 1799.

Nearly 60% of the German-speaking male population of the canton lost their lives in this war. Many died in the battle of Pfyn, named after the large pine forest still visible today below the village. Some of them are here.

Roger Mathieu-Uttenthal

"What you are, we once were. What we are, you will become".

© Cyril Zingaro for Le Temps

The wall of skulls has not welcomed any new occupants since 1860. "In the summer, students from good families returned to the village with nothing to do," explains Roger Mathieu-Uttenthal. "Out of boredom they did all sorts of stupid things, like stealing skulls." Since there was no longer such a shortage of burial plots, this increase in petty theft convinced the authorities to wall up the dead, who rested for 122 years out of sight. It was the renovation of the church above the chapel in 1982 that brought them out of the darkness once more.

Now visible, the ossuary wall fascinates visitors from all over the world – sometimes a bit too much. There is a noticeable dark space among the skulls. "It happened last summer", says the guide. "Suddenly, one was missing." The disappearance of a fellow skull does not seem to concern the wall's other occupants, who are waiting patiently to have the last laugh.

"What you are, we were. What we are, you will become," they tell us.

Adapted from an article originally published in French in Le Temps, Michel Guillaume, August 2018