The German doctor who created Davos

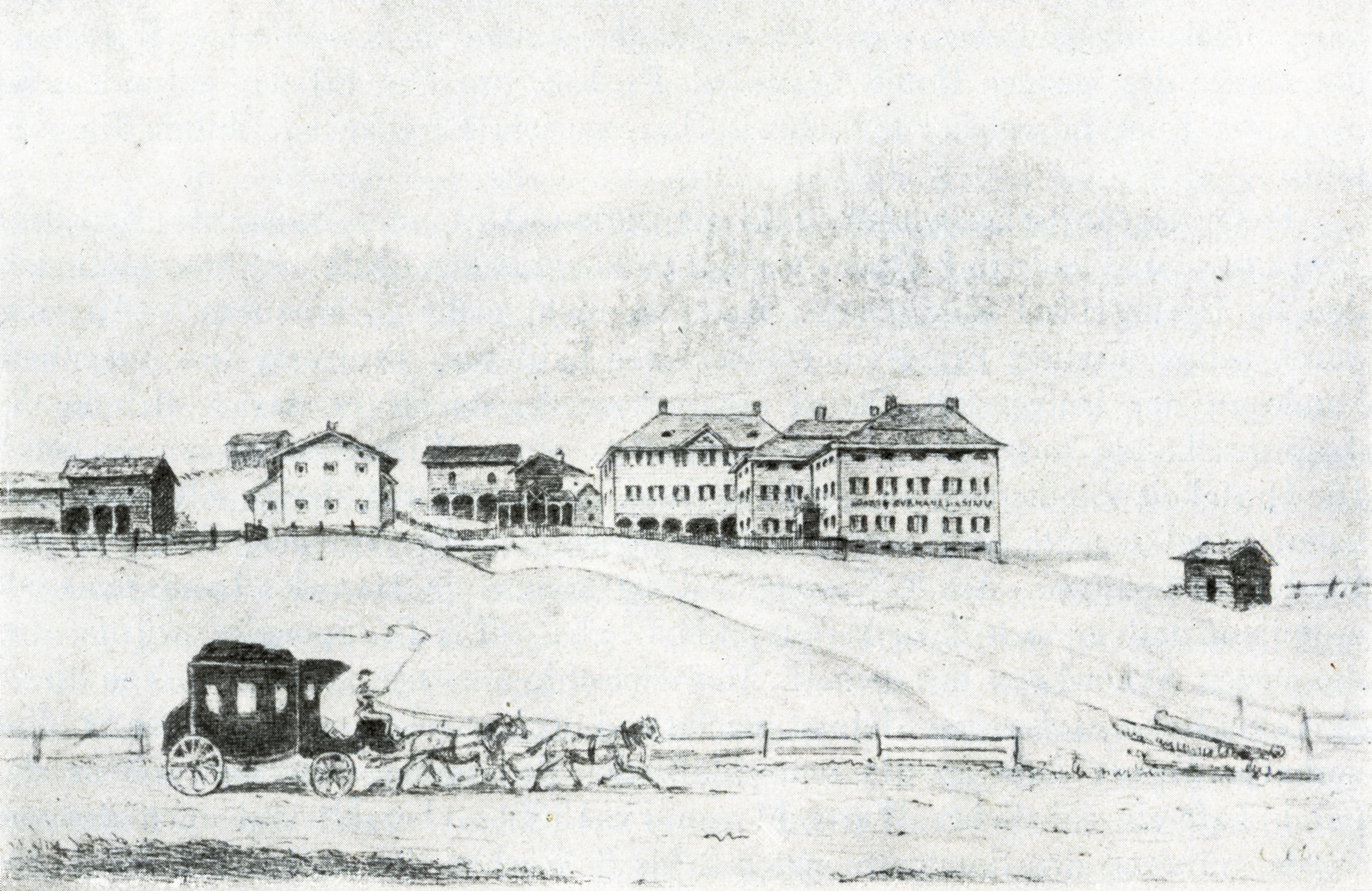

Davos in 1850 was a poor, remote village of a few scattered farmhouses, high up in the mountains of the canton of Graubünden. In 1900 it was a world-renowned mountain health resort and fashionable spa and tourist town. In 2020 Davos is a mountain resort with a cosmopolitan ambience and, at 1,560 metres, the highest town in the Alps. Thanks to the World Economic Forum, it has become a glamorous congress venue of global importance.

How did this remarkable transformation take place? A migrant and asylum seeker, Alexander Spengler, was the first to develop this mountain resort.

From revolutionary to country doctor

It was no doubt a grey, wintry day in November 1853 as the German doctor, Alexander Spengler (1827 - 1901), struggled along a bumpy track in Praettigau, travelling in a one-horse buggy from Zurich to Davos.

It was more than just coincidence that brought him to this remote region of the Landwassertal. He could just as easily have been dead, or in America. The former revolutionary, who had stood at the barricades of the Grand Duchy of Baden in 1849 as a lieutenant fighting for a new political system, arrived in Switzerland as a political refugee. It was even rumoured that he had been sentenced to death in absentia, although there is no documentary proof of this. The freedom fighter was allowed to study medicine in Zurich. In 1853 he seized the opportunity to become a country doctor in Davos. Two years later, Spengler, the asylum seeker, would become a naturalised Swiss citizen.

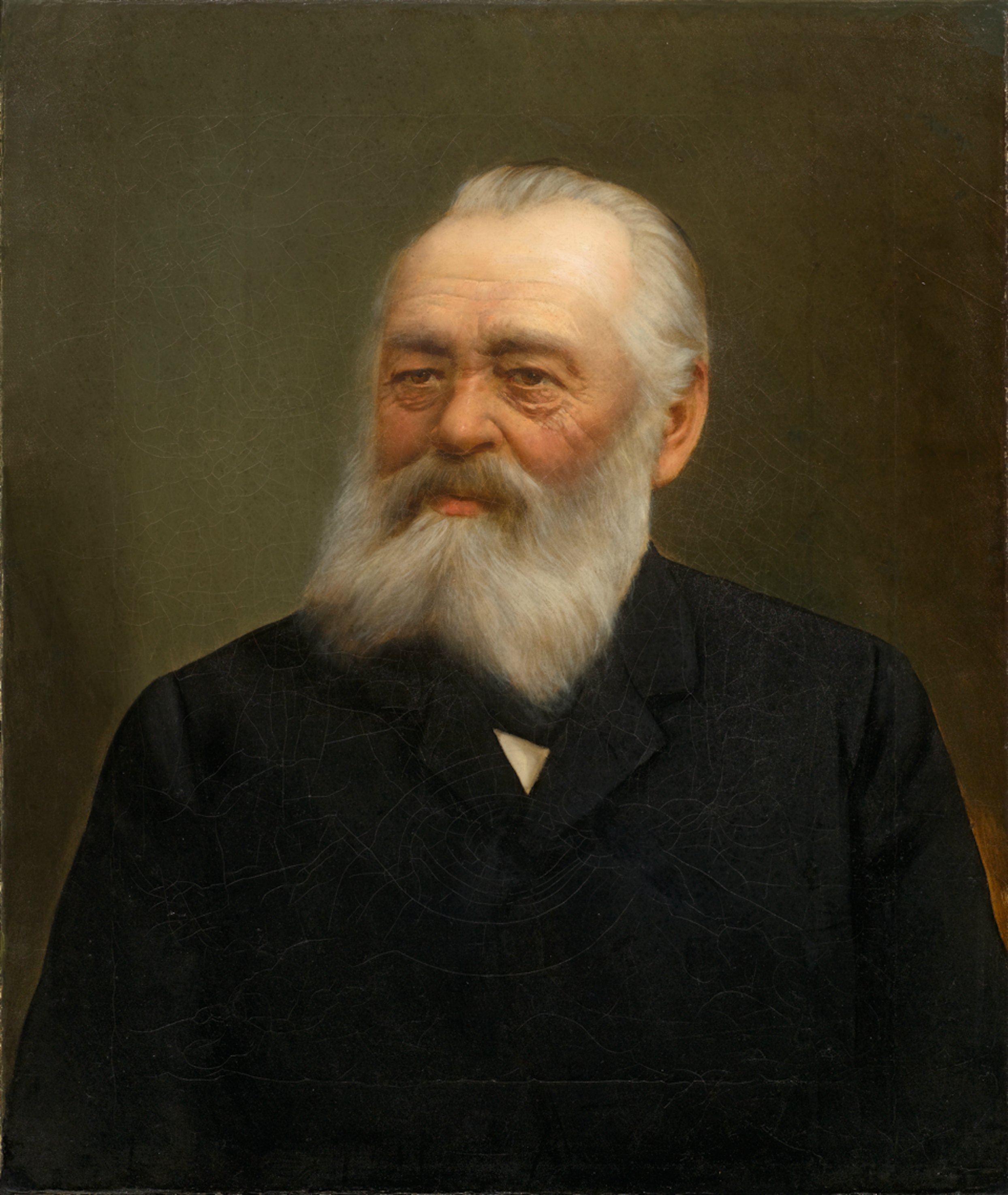

© Heimatmuseum Davos (restored at the expense of Samuel Miller, Davos)

Ideas of a madman

Initially the work in the remote mountain valley seemed to Spengler to be a form of exile. While his salary was low, his district was so large that the distances between house calls could only be covered on horseback. He was constantly homesick and also missed the intellectual stimulation, theatres and cafés of Zurich. But then two things happened: he found himself a companion, his future wife, Miss Elisabeth Ambühl, with whom he would go on to have a happy marriage and five children; and he made an exciting discovery, one that took hold of him. He observed that all the locals had "a beautiful, symmetrical body, a bulging chest and a strong heart muscle". He was astounded by their agility on the steep mountain paths "without perspiring or becoming breathless". Most significantly, he found no cases of tuberculosis. Could Davos be a place of immunity, free of the diseases which killed the rich and poor alike at that time? Consumption in its advanced stages was considered incurable. Those who could afford it travelled to spas in milder, southern climates, hoping for a cure.

© Dokumentationsbibliothek Davos

Spengler's idea of a spa high in the mountains, where cold, thin mountain air was prescribed even in winter, was initially dismissed by his colleagues as sheer madness. From the outset, it seemed that Spengler was using strange treatment methods, such as ‘stabulation’, which involved long stays in cowsheds, where lung patients were supposed to be cured by the ammonia-filled air.

But in the winter of 1865, two seriously ill German patients, the bookseller Hugo Richter and Dr Friedrich Unger, arrived in Davos exhausted from their nine-hour journey by sleigh. Over the winter they took a cure of fresh air, resting on improvised lounges of planks laid over large wooden sleighs, and their conditions improved quickly. This also changed Spengler's fortunes. The two convalescents became important living advertisements in the early days of the spa. Soon the sick were travelling to the mountains of Graubünden from all over Europe. In 1875, for the first time, there were more winter guests taking treatments than summer guests.

© Dokumentationsbibliothek Davos

Davos becomes the mecca for consumptives

Spengler prescribed his patients long walks, up to three litres of milk a day, nourishing but light meals, chest-rubs with the fat of marmots, which penetrates the skin more easily than other products, and, most importantly, ice-cold showers. Spengler noted that, as a result, the patient breathes "more easily and deeply, the pulse is full and strong, and the appetite adjusts itself".

It was an immediate success. Foreign investors were attracted, in particular the Dutchman Willem Jan Holsboer. He founded the first big spa hotel Hoelsboer-Spengler, together with Spengler, as well as the railway line from Landquart and the Schatzalp sanatorium.

© Michael Straub, Davos Wiesen

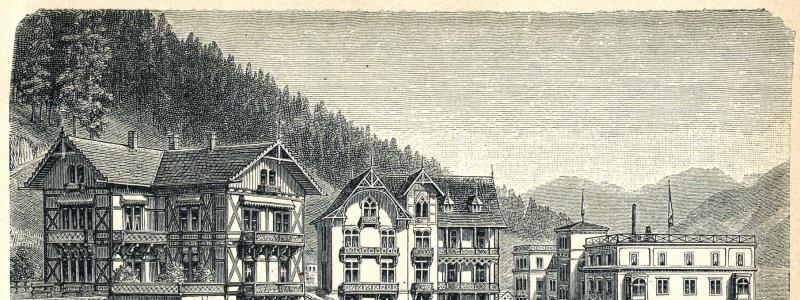

Within just a few decades, the poor hamlet in the Landwassertal grew into a stylish, metropolitan town, with electric street lights, horse-drawn trams and a cinema. Belle Epoque hotels and spas lined the streets. Men in frock coats of the finest material and ladies bedecked in mink strolled along the snow-covered streets, drank tea at five o'clock, and went to concerts of the spa orchestras. A babble of German, English and Russian could be heard on the ice rink and in the lobbies. The social life was vibrant.

However, Spengler, the former revolutionary, never forgot his roots and continued to work for the poor throughout his life. Destitute patients were provided treatment at the Alexander House, founded by Spengler and run by the deaconesses of Bern.

The spirit of Davos

An imposing figure with a long, white beard, the founding father gradually retired from 1890 onwards, suffering from the complaints of old age. New treatment methods had been found long before and his sons, Lucius and Carl, were among the leading therapists for tuberculosis, both employed as head physicians in the famous Davos spas. Carl seems to have inherited his father's feeling for timing and innovation. In 1923 he established an inter-nation ice hockey tournament to help young people cope with trauma after the First World War. It still enjoys international renown today as the Spengler Cup.

© Michael Straub, Davos Wiesen

Alexander Spengler died in 1901, but his drive and medical and entrepreneurial success stories live on in Davos today. If Spengler's arrival had not led to the astounding transformation of old Davos into a cosmopolitan spa, Thomas and Katia Mann would never have gone to the Schatzalp Sanatorium. And Davos would never have become known in world literature as the setting for the novel The Magic Mountain (1924). Even less likely would a mountain village at 1,500 metres have become a meeting place for the global economic and political elite. Nevertheless, since 1971, the illustrious guests of the WEF have found the spirit of Davos extraordinarily inspiring. The pioneering spirit was first brought to this mountain valley in Graubünden by a foreigner, an asylum seeker.