Maurice Koechlin, the Swiss who designed the Eiffel Tower

The Eiffel Tower has Swiss roots! The statement might seem a little pretentious, but there really is a Swiss connection to the famous tower – the French-Swiss engineer Maurice Koechlin.

Switzerland has a significant link to the Eiffel Tower: Maurice Koechlin may not be as renowned today as Gustave Eiffel, but he drew the first sketch for the tower and remains its true creator. His great-grandson Jean-David Koechlin reflects here on the tales he heard growing up, as well as on the story of an ancestor who was Gustave Eiffel's employee, his friend, and finally his successor.

From Mulhouse to Zurich

The story begins on the banks of the Rhine in Mulhouse, France. With the financial support of nearby Basel, the city had become one of the 19th century's key industrial hubs – its success was so phenomenal that it was dubbed 'the French Manchester'. "Everything was possible for them – they believed in progress," explains Jean-David Koechlin. When the Franco-Prussian war broke out in 1870, however, Mulhouse fell to the Prussians. A number of the great Protestant families who had helped Mulhouse flourish fled the city. This included Maurice Koechlin's family, who settled in Switzerland. Maurice's father sent his children to the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, one of the world's leading technical universities for engineering.

Recommended by his professor

Koechlin, who was the oldest of his siblings, decided to take up the Swiss citizenship his family held before they moved to Mulhouse. In Switzerland he studied under a brilliant professor by the name of Karl Culmann. A specialist in 'graphic statics', Culmann taught Koechlin a revolutionary method for using box girders to build remarkably tall structures. Thrilled by this Swiss expertise, the great Parisian developer Gustave Eiffel asked Culmann to recommend him a student. Koechlin was such an enthusiastic pupil that Culmann suggested him to Eiffel.

From lofty ambitions...

In November 1879 Maurice Koechlin was hired to work for the metal construction and public works company founded by Gustave Eiffel in 1868. He soon began work on the Garabit railway viaduct in Auvergne, an audacious project that was inaugurated in 1884 and towers 122 metres above the river below. Koechlin made innovative use of bridge piers that are strikingly reminiscent of the tower he would later work on. He then worked alongside the engineer Auguste Bartholdi, a fellow Alsatian, on fine-tuning the steel framework of the Statue of Liberty in New York.

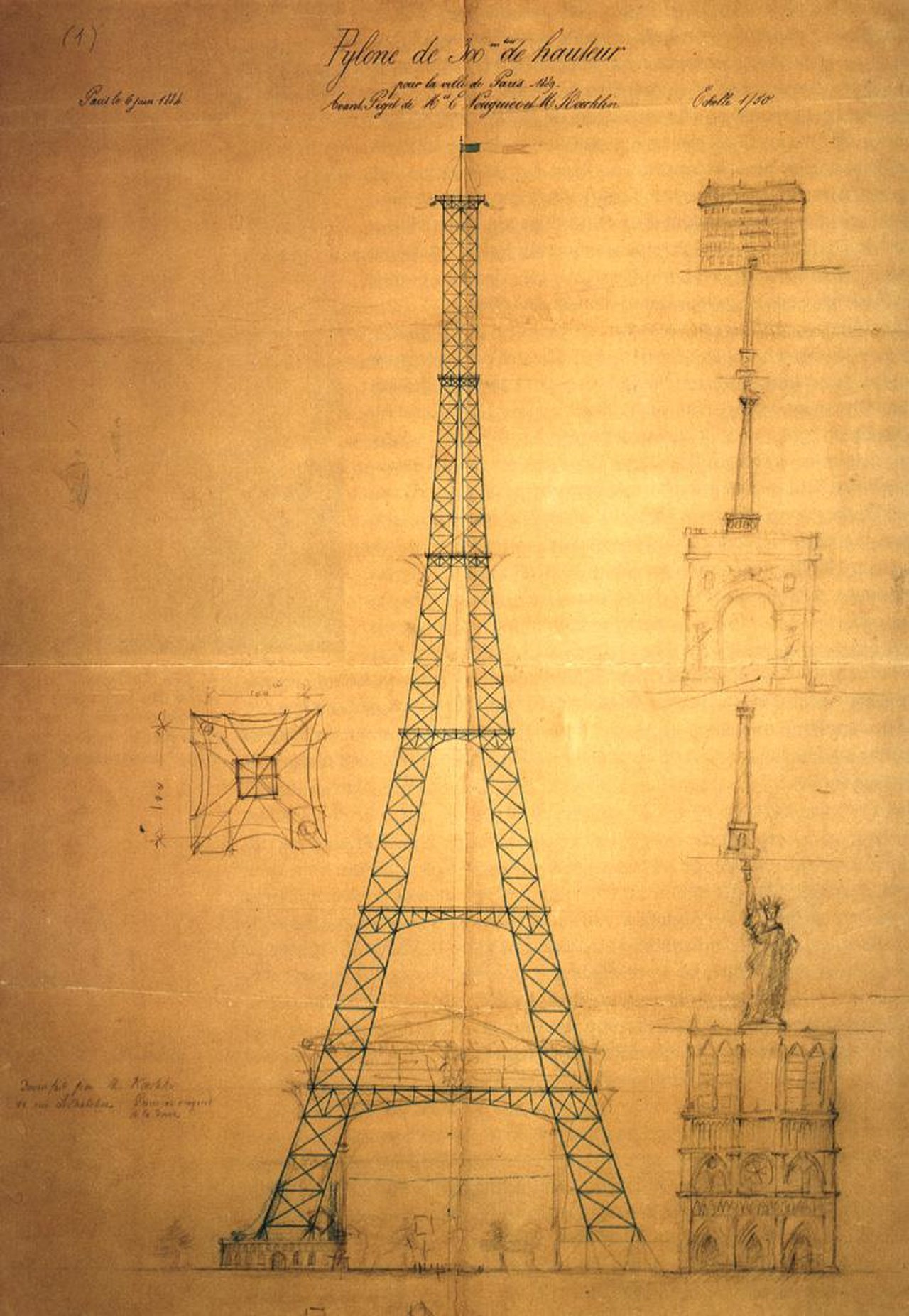

In 1884 Koechlin became the head of Eiffel's engineering department at the age of 28. The Universal Exhibition in 1889 offered a chance to make a lasting impression: working alone and bolstered by his recent experience, Koechlin drew a sketch for a tower that reached the symbolic height of 1,000 feet (300 metres) – taller than any existing structure. Until then, Cologne Cathedral had been the world's tallest monument at 150 metres. Koechlin referred to his project simply as the "pylon".

"Through his trust in human intelligence he reached the apex of what was possible," says Jean-David Koechlin.

The following day Koechlin discussed the sketch with technical director Émile Nouguier. The two men presented it to Gustave Eiffel, who was less enthusiastic. While he recognised the boldness of the concept, Eiffel didn't find it aesthetically pleasing and encouraged the engineer to rethink the design. "Although he was impressed it reached 1,000 feet, Eiffel wanted other features, such as the inclusion of a large arch." So Koechlin went back to the drawing board. Together with his colleague he called on the company's head architect, Stephen Sauvestre, who hit on the ingenious idea of 'embellishing' each of the tower's levels. As well as the arch at the base of the tower, he added a large conference centre on the first floor that was never built. He also made generous use of ornamentation, placing statues of figures sounding trumpets at the corners of the tower's second level.

...to a magnificent tower

This time round, Gustave Eiffel was won over by the project. He found the tower magnificent, and even anticipated potential technical additions such as illumination and optical telegraphy. He imagined it as a beacon that would illuminate all of Paris. Throughout the rest of his life, Eiffel used the tower to conduct various experiments, for example dropping objects from different levels to test Newton's theory of gravity.

Alongside Koechlin and Nouguier, Eiffel submitted a patent application 'for a new configuration allowing the construction of metal supports and pylons capable of exceeding a height of 300 metres'. Shortly afterwards he bought the patent rights from the two engineers, who each received the equivalent of 1% of the construction costs. Eiffel thus became the project's sole founding father: as a powerful and widely recognised industrialist, he alone could see the project through to its conclusion. Koechlin focused on managing the construction process: not one of the 18,038 construction elements was used without his authorisation.

From ephemeral to enduring

In January 1887 Gustave Eiffel won the competition launched for the Universal Exhibition with his project for a 300 metre-high tower. The tower was originally due to stand only for the duration of the exhibition, from 6 May to 31 October 1889. It was built in two years, two months and five days and inaugurated on 1 March 1889. Because of its success and robust deign, however, the tower endured long after the Universal Exhibition.

Friends in high places

Maurice Koechlin, who succeeded Gustave Eiffel as the head of the Eiffel construction company in 1893, didn't seem to begrudge his boss for acquiring the project. As his great-grandson, Jean-David Koechlin, explains:

There was never the slightest ill-will between Eiffel and my ancestor, who went from being his employee to his successor. The two were actually on excellent terms – they were friends. Eiffel, who was 24 years older than Koechlin, was a frequent visitor to the Swiss Riviera. I'm convinced he showed Koechlin the region, and likely also the house my great-grandfather bought and lived in towards the end of his life.

Imitations around the world

Today the Eiffel Tower is an international icon of France and a showcase for the city of Paris, as well as one of the world's most visited monuments with an entrance fee.

Though none can truly match it, the tower has inspired many imitations around the world, the oldest being Blackpool Tower, which was built in 1894 in the north of England. The replica in Las Vegas is the most famous copy, but the Parisian tower has also inspired close imitations in Paris, Texas and Paris, Tennessee, as well as in Tokyo, Shenzhen and Hangzhou in China, Prague, and Slobozia in Romania.

Article originally published on L'Illustré and adapted, Marc David, on 3 November 2021