The mystical and mythical edelweiss

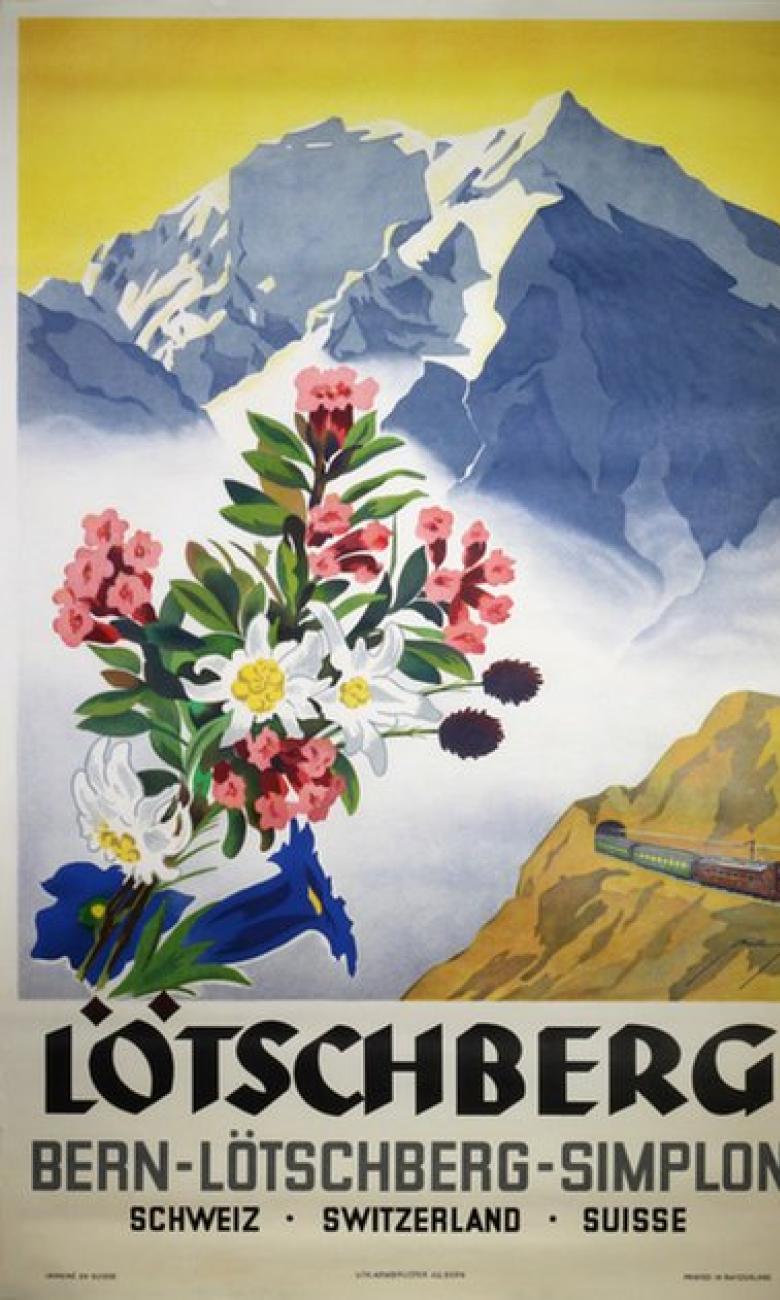

The edelweiss, a delicate mountain flower with furry white petals, is so strongly associated with the Alps it is hard to believe it originated in the Himalayas and Siberia. It was not until the second half of the 19th century that what botanists in Zurich previously called the ‘wool flower’ became widely known as edelweiss and took on a special cult status in Switzerland. The flower has attracted admirers and critics over the years but remains one of the most iconic images of Switzerland, adorning everything from airlines to coins to the logo for the Swiss tourism office.

A flower of many flowers and with many names

The edelweiss, or Leontopodium alpinum as it is scientifically known, is technically not a single flower but more than 50 to 500 tiny florets clustered in 2 to 12 yellow flower heads (capitula), surrounded by 5 to 15 velvety white leaves (bracts) arranged in the shape of a star.

Scientists believe the flower migrated from Asia to the Alps during the Ice Age. Today, it can be found in many Alpine countries at high altitudes (2,000 to 3,000 metres), with the highest recorded sighting at 3,140 metres just above Zermatt. It blooms from July to September on exposed limestone rocks, but it can also be found at the edge of meadows. Since the 1990s it has been cultivated at lower altitudes and is increasingly found in private gardens.

Despite its delicate appearance, every one of the flower’s organs is designed to withstand extreme weather, from the wind-resistant underground stems to leaves that prevent evapotranspiration to the UV-protective microstructure of the hairy bracts. This makes it particularly attractive for use in anti-aging cosmetics and sunscreen.

The unique features and appearance of the edelweiss have inspired many names, starting with the first mention of the Wollblume (‘wool flower’) by Zurich naturalist Konrad Gessner in the 16th century. Klein Löwenfuss (‘small lion’s foot’), étoile du glacier (‘star of the glacier’), étoile d’argent (‘silver star’) or immortelle des Alpes (‘everlasting flower of the Alps’) have all been used by various botanists and biologists to describe the flower.

The first written trace of the name edelweiss, which in German means ‘noble white’, appeared in a 1785 study by Austrian naturalist Karl von Moll, but it wasn’t until the mid-19th century that the name caught on when several famous German-speaking botanists started using the name. Since this time, the name edelweiss has transcended languages and borders.

The cult of the noble white flower

How did the edelweiss overshadow other mountain flowers like the Alpine rose, widely viewed to be aesthetically more beautiful? Following a trip through the Bernese Alps in 1881, the American writer Mark Twain called the edelweiss the “ugly Swiss favourite” and described the flower as neither attractive nor white but said that the “fuzzy blossom is the colour of bad cigar ashes”.

However, Twain was too late. By the time critics started questioning whether the flower was worthy of its cult status, myths about its mystique and exceptionalism were already widely accepted. These myths were intimately tied to the boom in alpinism in the mid-19th century and the values of courage and strength associated with the sport.

One of the greatest myths about the flower is its inaccessibility. Tobias Scheidegger, a senior researcher of popular culture at the University of Zurich, who researched the edelweiss for a 2011 exhibit at the Botanical Gardens in Geneva and Zurich, argues that the popular belief that the flower only grows on ice and steep rock is botanically not true. He explains, “It was actually the alpinists themselves who popularised this image to promote themselves as brave, strong men.”

One of the most famous stories about the edelweiss is of a young man risking his life climbing the steep rocky face of a mountain to gather edelweiss flowers for a woman as a demonstration of his love and bravery. In the 1861 novel ‘Edelweiss’, German author Berthold Auerbach exaggerated the difficulty of acquiring the flower, claiming: “The possession of one is proof of unusual daring.”

The flower was also believed to possess magical powers. The first mention of the edelweiss by Moll described a conversation with a farmer in the Zillertal valley, Austria, who argued that when used as incense, the flower’s smoke drives away spirits that attack livestock and cause udder infections. The flower was said to aid digestion and treat respiratory illnesses like tuberculosis. Its medicinal benefits were perpetuated later in poems and stories: for example, in the 1970 classic Asterix in Switzerland, Asterix and Obelix are sent on a search to find edelweiss or what is known as ‘silver star’ for an antidote to a poison.

The edelweiss was also used to make political statements at different points in history. In the 19th century, the flower represented a paradise at a time of scepticism about Europe’s growing cities. The flower was also a controversial symbol of nationalism in Germany and Austria, as the favourite flower of Adolf Hitler but also the emblem of the Nazi resistance movement, the Edelweiss Pirates. The famous ‘Edelweiss’ song, created for the 1959 Broadway musical and film adaptation of ‘The Sound of Music’, was a statement of Austrian patriotism in the face of Nazi pressure.

Although the flower was not used to promote nationalism in Switzerland, it has helped shape national identity. Scheidegger explains that, “Switzerland, like many countries in Europe, went through a period of reflection after the Berlin Wall fell. The edelweiss became an important part of redefining what it means to be Swiss.”

From kitsch to cool

As tourism flourished in Switzerland, the obsession with the edelweiss eventually endangered it. Tourists and mountaineers picked the flower as a souvenir of their travels. The canton of Obwalden banned people from digging up the plant’s roots in 1878 in what is considered one of the first environmental protection laws in Europe. Today the flower is not listed as an endangered species at the federal level, but several cantons include it as a protected plant.

Although the edelweiss is no longer considered rare, its mystique and value to Swiss cultural life remain. Scheidegger explains that in the mid-20th century, the edelweiss was considered kitsch. “It was largely featured on cheap souvenirs and lost some of its attractiveness. However, there was a rebranding in the 1990s that helped revive the edelweiss. This was strongly tied to the concept of reimagining traditions and embracing the country’s roots and heritage.”

Today, the edelweiss not only represents a connection to the nature and beauty of Switzerland but is a trademark of Swiss quality and uniqueness. In Switzerland, the image of an edelweiss flower adorns everything from advertisements for dental offices to the 5 franc coin to the rank insignia for the Swiss Armed Forces. Its value extends beyond the Alps, with many of today’s companies bearing the edelweiss name and image. A financial services company in Mumbai, a chocolate company in Beverly Hills, and a delicatessen in New York are all named after the flower.