Sheikh Ibrahim, the Swiss who discovered Petra

Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, the scion of a wealthy Basel family, converted to Islam to facilitate his work as an explorer. In 1812, travelling almost alone, he discovered the lost red sandstone city of Petra in the Jordanian desert.

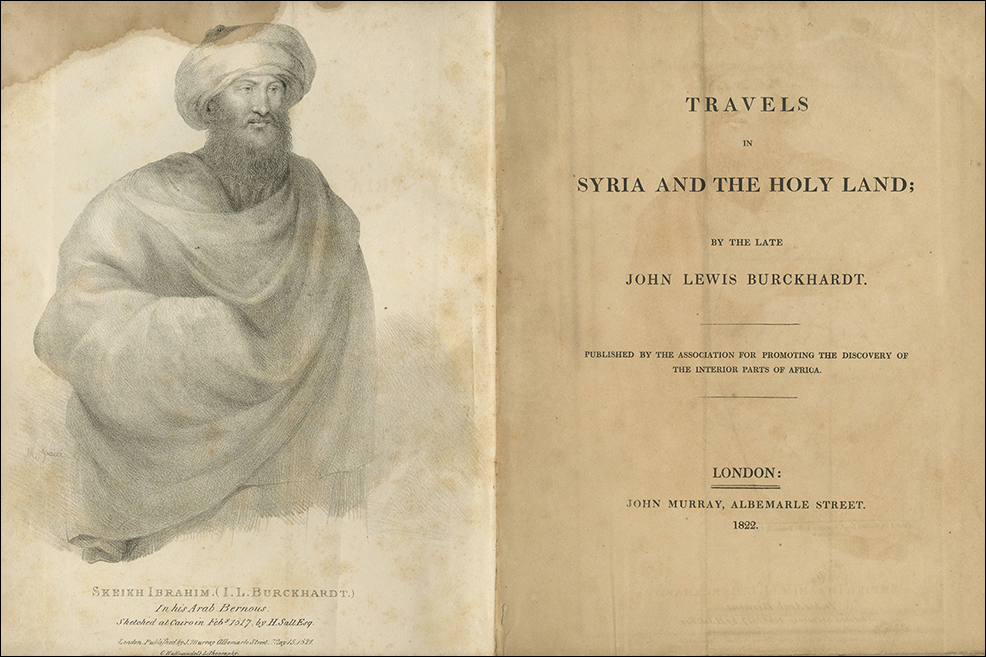

The lost city of Petra, which has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1985, was rediscovered in 1812 by the Swiss explorer Johann Ludwig Burckhardt. Also known in French as Jean Louis Burckhardt and in English John Lewis Burckhardt, this Swiss explorer and orientalist entered the annals of history under the alias Sheikh Ibrahim Ibn Abdallah. He came to be recognised as one of the greatest explorers of his time as the man who rediscovered Petra, a treasure of the ancient world located some 4,000 kilometres from Switzerland.

Adventurer in the making

Born to a large, wealthy family that had emigrated to Lausanne after Napoleon's troops entered Basel in 1798, Johann Ludwig Burckhardt studied law, philosophy, history and languages at the universities of Göttingen and Leipzig. After his studies, he moved to England, where he took employment at the African Association, whose stated mission was to help Britain beat France in the exploration of the African continent and exploitation of its riches. But Burckhardt was no hot-headed adventurer. He entered a rigorous course of study at Cambridge, where he began to study Arabic.

In 1809, he left England, making a brief stopover in Malta, where he assumed a new identity as Ibrahim ibn Abdallah. In his travel writings, Burkhardt explained that he passed himself off as a Muslim Indian merchant to allay suspicions about his accent and imperfect command of Arabic. Whenever he was asked to say a few words in the Indian language he claimed as his mother tongue, he would launch into the broadest Swiss German dialect to dispel suspicions.

Some did wonder about his true origins, however. After reaching Aleppo in July 1809, he spent two years working on his Arabic, both the spoken vernacular and the classical language of the Quran, and learned to recite some of its verses by heart. "You wouldn't recognise me, sitting on the ground in loose-fitting Turkish robes and sporting a respectable beard," he wrote his parents. He undertook small expeditions around Aleppo, where he developed a fascination for the Bedouin tribes he encountered. He realised that he had to exercise caution: to make an entry in his notebook, he would move away from prying eyes, remove it from its hiding place under his turban and shield his hands with his robe.

A perilous discovery of inestimable value

In 1812, Burkhardt left Aleppo, travelling without a map in search of ancient sites whose location he had committed to memory. In August he asked some local guides to take him to Mount Aaron, which he believed to be near the Nabatean city of Petra, pretending that he wanted to sacrifice a goat at Aaron's tomb. On 22 August, he managed to convince a guide of his good intentions. In his Travels in Syria and the Holy Land he describes in sober terms the spectacle that opened up before him after a thirty-minute walk through a narrow gorge. He adds that he was not able to explore the palaces and tombs as freely as he would have wanted to, as this would have aroused his guide's suspicions that he was there to plunder treasures or, worse, practise black magic. He did not doubt for a moment that he had made a discovery of immeasurable value. "Future travellers may visit the spot under the protection of an armed force; the inhabitants will become more accustomed to the researches of strangers," he wrote.

Passion for ethnology

Burckhardt did not want to jeopardise the project that was closest to his heart and which he would never be able to realise: to explore the source of the Niger. He arrived in Cairo in September 1812 and undertook two expeditions in the Nubian desert. It was there, in 1814, that he discovered the monumental columns of the temple of Abu Simbel. The significance of the site is universally recognised today but Burkhardt mentions it only in passing in his writings. A passionate ethnologist, he described the people he encountered and the political power relations of the places he visited in a style that stands out for its objectivity.

Religious conversion

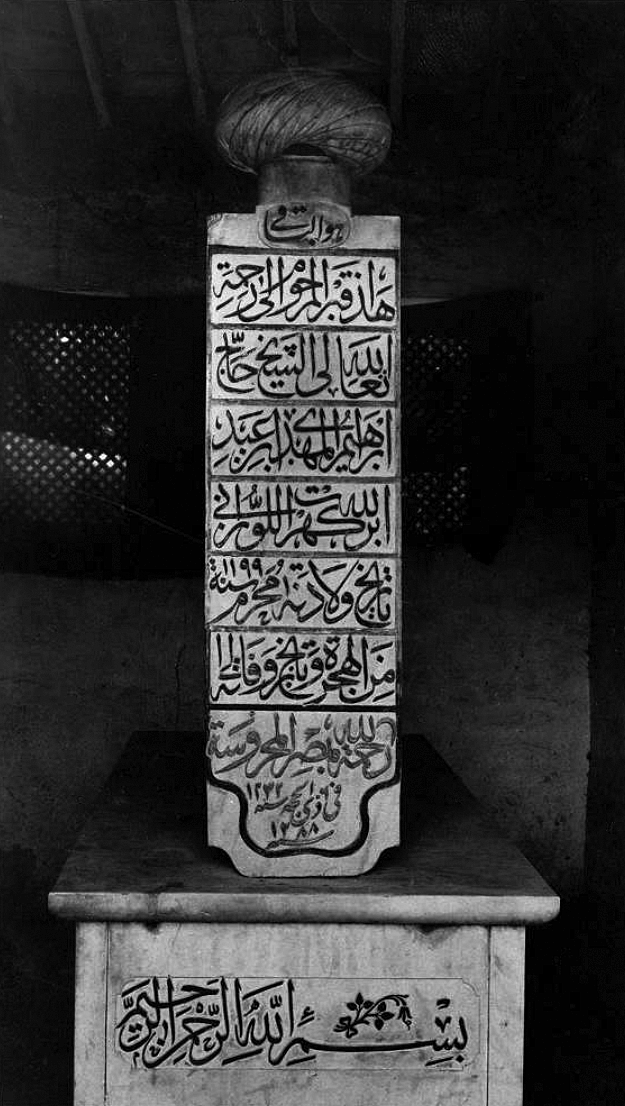

From his pen also comes the first description by a Westerner of the holy places of Mecca, where he made a two-month pilgrimage. It is not known whether his conversion to Islam was genuine or not, but what is clear is that this was a risky undertaking for a European. He never mentioned the subject in letters to his family. Nevertheless, it was as a haji – a Muslim who had made the pilgrimage to Mecca – that he was buried in 1817 in Bab el-Nasr cemetery in one of the most densely populated districts of Cairo.

Article originally published in Le Temps, Catherine Cossy, January 2013