The Rorschach test, invented by a Swiss psychiatrist, turns 100

The world's best-known psychological personality test – the Rorschach inkblot – was created in Switzerland 100 years ago. Despite its somewhat mysterious nature, the test continues to be a mainstay of present-day culture and is still used in diagnosis.

What could it be? An ink blot. Symmetrical. Strange. Rather beautiful... yes, but what else? It looks like a bat. Or a butterfly. Or the skin of an animal, spread out? Or could it even be an x-ray of someone's pelvis? All of this probably sounds very familiar. Maybe because it conjures up an image of a therapist and their patient, who's just been given the Rorschach test. Or maybe you've tried this globally recognised psychological test yourself. Or maybe you've come across it on screen somewhere – because 'the Rorschach' is everywhere: in a piece by Warhol, a number of films, and even one of the characters in the cult comic book series Watchmen. And although controversial, it has withstood the test of time, its success reaching far beyond the borders of Switzerland.

Artistic influences

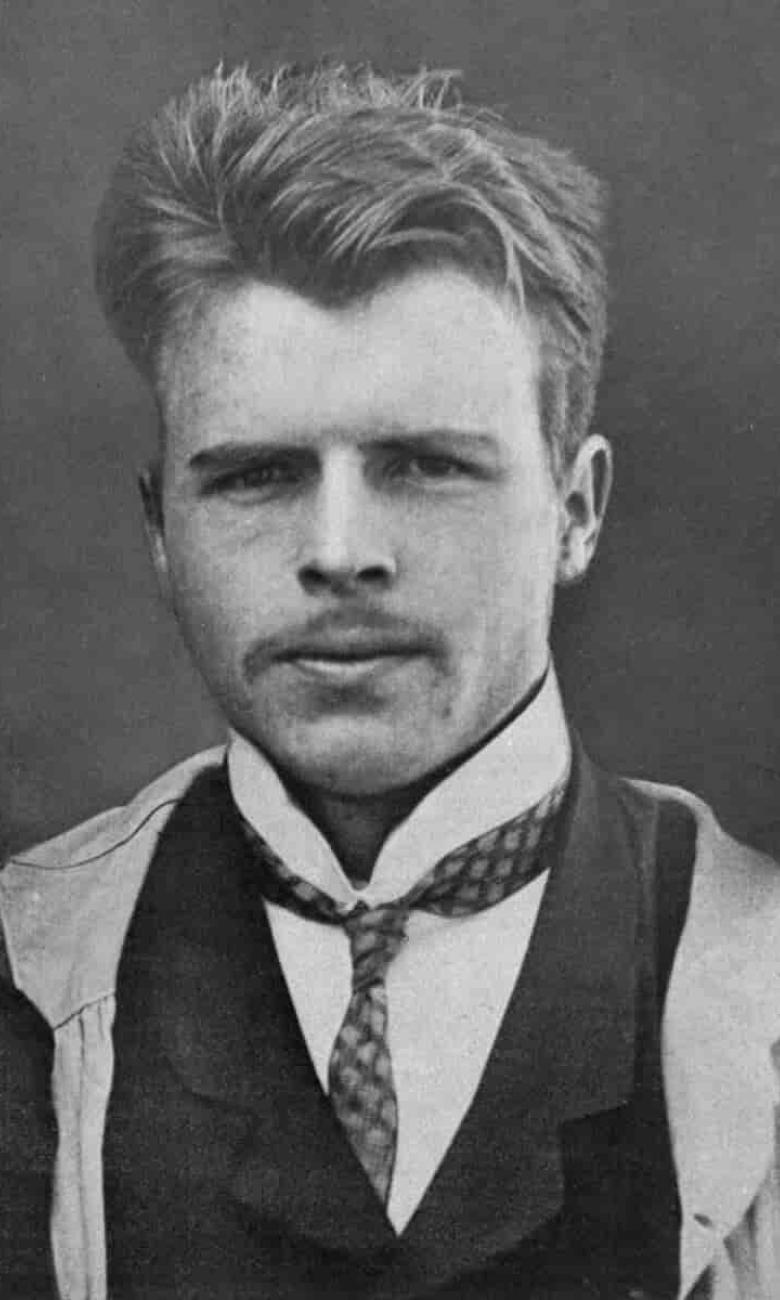

The Rorschach test was developed in Zurich and is named after the psychiatrist who invented it, Hermann Rorschach (1884–1922), who used to practice at the Psychiatric University Hospital Zurich, known as the Burghölzli. Rorschach's professor and PhD adviser was Eugen Bleuler, famous for having coined the term schizophrenia and been instrumental in introducing psychoanalysis to Switzerland. As for Rorschach, whose father had been an art teacher, there was a considerable period of hesitation before he opted for a medical career over an artistic one. Since then, the Rorschach test has become known all over the world.

Optical illusions

"Hermann Rorschach had a keen interest in optical illusions. During his time in Russia, he collected newspaper drawings that often showed hidden elements behind the main image. What interested him was the ambiguous nature of such composite images, like a cat-frog or a squirrel-cockerel," explains psychologist Sadegh Nashat, a lecturer at the University of Geneva and authority on Rorschach's work, whose archives he has studied at the University of Bern.

Rorschach created his test by developing around a hundred different studies of inkblots of varying degrees of complexity, but each one showing an (imperfect) mirror symmetry. "The inkblots used in the test weren't just created by chance. They were the result of meticulous work, with Rorschach reworking every detail. He used to test them out on young people who had been institutionalised and schizophrenics, asking them what they saw. By studying the different responses, Rorschach thought he could identify different pathologies and personality traits," adds Nashat.

Rorschach set out his method in his book Psychodiagnostik (Psychodiagnostics), which was published in 1921. But the young doctor didn't have long to continue his investigations – the following year, at the age of 37, he died suddenly from poorly-treated peritonitis, leaving behind his wife and two children and his life's work unfinished. "Rorschach himself saw his test as a work in progress and warned against making hasty interpretations from using it," explains Jacques Van Rillaer, professor emeritus of psychology at the University of Leuven in Belgium.

Difficult to manipulate

After a somewhat frosty reception from his colleagues at the start, Rorschach's test gradually gained in popularity after his death, particularly after 1940 when it started to spread to all four corners of the world – most notably in the US, France and Japan. The test is still widely used in clinical practice, forensic examinations and recruitment. "The advantage is that it's very difficult to manipulate – unlike a questionnaire, for example, which you can try to spin," explains Nashat. Numerous scientific studies have been carried out on the Rorschach test – 118,000 dedicated publications alone according to Google Scholar.

The test is still conducted in the same way as it was 100 years ago. The therapist shows the patient the same ten inkblots and asks them what they see, recording everything they say in detail. This is then interpreted not only by what they say – a few mundane responses like 'it's a spider or a butterfly' are par for the course – but how they analyse the image. Does the patient look at the image as a whole, or focus on the details? Do they pay more attention to the colours or the shape? Do they notice the texture? And so on.

While this information is supposed to reflect how the person ticks, how does it work exactly? Rorschach didn't leave a key on how to interpret responses to his test. In fact, there are two main approaches that still exist to this day. In the French-speaking world, many therapists that use the Rorschach test rely on psychoanalysis. "Rorschach was a psychoanalyst too, but he didn't include his test in this approach. The problem is that there's too much room for interpretation, so a therapist might reach a different conclusion even from the same set of answers," criticises Nashat.

Supporters and detractors

Nashat follows the Anglo-American approach, based in particular on the work of the American John Exner who synthesised the various ways of interpreting the Rorschach test in the 1970s. This was done in order to develop a statistics-based analytical procedure to make the responses of different therapists more consistent. "This approach has proven to be effective in identifying suicidal tendencies, diagnosing psychotic episodes and evaluating PTSD," he explains.

But the method hasn't been approved by everyone, including Van Rillaer. "Yes, different therapists using this method do come to similar conclusions. But that doesn't mean they're right! This is a test that pathologises people to a large degree. And this also makes it particularly problematic when used for legal expertise – because any conclusions that are made based on the test are questionable, to say the least," he adds.

Nashat, however, continues to champion the test and uses it routinely in his work: "The Rorschach test is only valid when used in combination with other psychological tests, not as a stand-alone. It can be very useful for understanding what a patient finds difficult, or what resources they have. It also helps to open up the discussion. When you show the patient their results, it often allows you to address some key points that would not have come up spontaneously in a normal consultation." So, is the Rorschach test a window into the human soul or like reading tea leaves? 100 years on, the mysterious inkblots continue to defy at least some of our interpretations.

Article originally published in Le Temps, Pascaline Minet Guillaume, 14 October 2022.