'Swiss Tattoo': Swiss quality under the skin

With 'Swiss made', you know what you're getting: perfect execution, a five-star finish and impeccable quality. This know-how also applies to the Swiss tattoo scene; the country can boast a generation of tattoo artists whose unique talent has earned them international renown.

This is according to Clément Grandjean, a journalist with a passion for the needle, in his book 'Swiss Tattoo'. Grandjean spent 18 months meeting professionals and specialists, unearthing incredible archives to trace the history – and ink a portrait – of this particularly fertile Swiss practice.

As the Instagram hashtag #swisstattoo (150k) gets ready to dethrone #swisscheese (170k), an interview with the author of the first anthology dedicated to the Swiss tattoo.

Where has the current interest in tattoos come from, especially in a small country like Switzerland?

Like everywhere in Europe, the tattoo scene has exploded in Switzerland in recent years. There are thought to be more than a thousand tattoo artists in the country. Unlike in Japan or the United States, the birth place of the flash tattoo [a small tattoo chosen from a catalogue], we are far from being able to boast a heritage in this area. Nevertheless, some of the biggest names on the international scene are Swiss: Happypets, in Lausanne, Maxime Plescia-Büchi, who opened the famous Sang Bleu studios in London, Zurich and Los Angeles, and of course Filip Leu, the best tattooist in the world according to the profession as a whole, who specialises in large Japan-inspired pieces. People come from all over to Sainte-Croix (VD) to get a tattoo from him, that's quite something! I wanted to understand this paradox, which I believe is typically Swiss.

© Clément Grandjean

So you travelled the country in search of the 'Swiss made' tattoo. Did you find it?

Yes and no. From a stylistic perspective, we haven't invented much, I may as well say that straight out. In terms of designs, there is no ‘Swiss school’ as such, except perhaps for the fondue caquelons of David Mottier, with his tongue-in-cheek take on our national folklore. Our trademark, though, is technical perfection, the mastery of certain styles, the famous 'Swiss quality'. Borrowing from other traditions to enhance our know-how is something our country has always done well, and that's exactly what the pioneers did in the 1970s, in particular Felix Leu, Filip's father. His openness to the world, unique at the time, immediately put Lausanne on the tattoo map in Switzerland and then internationally.

© Clément Grandjean

Can you tell us a little more about the Leu family and their pioneering role?

Felix and Loretta Leu were immersed in the world of contemporary art. They travelled a lot and worked for Jean Tinguely (Felix's father-in-law) and Niki de Saint Phalle. Felix discovered tattooing somewhat by chance, but his artistic approach and business acumen soon made the family business a global success, first in Goa, then in Lausanne. They were among the first to use gloves, to disinfect their needles and set ethical standards. These practices had an important impact internationally.

In Switzerland, the Leu family business turned out a whole generation of trained tattoo artists. Their know-how exported well, since here we had the means to go off and perfect our skills in the studios of the big names or at international conventions. Because of this history and its high living standards, Switzerland still attracts many tattoo artists today.

© Clément Grandjean

Of some 1,000 tattooists, in your book 'Swiss Tattoo' you choose to highlight just 32 hugely different artists. What makes this necessarily arbitrary selection special?

My choice was subjective and obviously debatable, but it reflects the reality of the Swiss tattoo scene today, with its diversity of styles, generations and regions. Some of the profiles are my personal favourites. It's an underground scene in constant flux, so it's not easy to capture every facet. I do think, though, that this selection showcases the various heritages that have emerged around a unique set of skills.

Who are today's Swiss tattoo artists?

In recent years, we've seen the emergence of what you could call the 'ECAL generation', after the art school in Lausanne. The vast majority of new tattoo artists are graphic designers who continue to perfect the art of tattooing technically, exploiting the tricks of 'Swiss made' design and typography, which include the use of ink traps, small graphic details that make it possible to control the spread of ink over paper. Their shop window is no longer the specialist press but rather Instagram – that's where it's all at today.

© Clément Grandjean

How are these changes perceived in the community?

For some, Instagram is the only way to communicate with their customers, which is sometimes difficult because the algorithm is unpredictable. Today's tattoo artists showcase their own work, and much of their success depends on their ability to retouch photos, generate likes and communicate. This has also elevated some of them to stardom, giving them the freedom to take more radical approaches and pick and choose their projects.

So infinity wrist tattoos, lettering and the like are a thing of the past?

Not at all. Walk-in flash tattoos are still a large part of the business and shouldn't be looked down upon. Many reputable studios still do it and I think it's important that they keep doing it if tattooing is to remain truly accessible. Although it is also an art in its own right, tattooing is primarily a craft and customer-oriented. The design is basically a pretext. Whether it's a full backpiece signed by Filip Leu or an infinity symbol, I think that all clients approach this encounter with their body and with the pain in the same way.

© Clément Grandjean

This moment of concentration on the breath to manage your pain has cathartic properties, and it has something of a rite of initiation.

Clément Grandjean

How do you explain the current unprecedented hype around tattooing in Switzerland and elsewhere?

The pioneer generation fought to restore the status of a practice that was stigmatised in Europe because of its association in recent times with marginalised groups. Now we are seeing the results. More than ever in this fast-paced world, I believe that tattooing fulfils a universal need. This moment of concentration on the breath to manage your pain has cathartic properties, and it has something of a rite of initiation.

What do you say to those who see it as a passing fad?

People have always been fascinated by tattoos. It goes back to our most ancient ancestors. It's at least as old as Ötzi – the oldest known tattooed person, who lived some 5,000 years ago...in the Austrian-Italian Alps, a stone's throw from here. I've seen tattooed skin samples from the late 19th century in the Museum of Anatomy in Basel, which clearly show that people were tattooing milking scenes and Swiss crests long before Instagram. Who knows what other treasures might be unearthed from Switzerland's tattooed past...

The taboo that has long surrounded it has hindered the emergence of an objective and intelligible discourse on the importance of the tattoo in our societies and what it says about the evolution of our relationship with our bodies. Switzerland is no exception, but this is finally changing.

From the Neolithic to Sainte-Croix, transported by the sailors of Basel, the history of Swiss tattooing

In the second half of the 18th century, Captain James Cook disembarked from New Caledonia accompanied by a Polynesian man covered in blue ink. It is said that the tattoo made its grand appearance in Europe when the British explorer returned home around 1770. It was apparently love at first sight for sailors from all over the Old World, who quickly appropriated this practice seen as exotic and began to ink designs derived from their own set of cultural references: hearts, mermaids, dates, initials and crosses.

Switzerland was also part of this European trend, which arrived in Basel with sailors passing through on the Rhine, notes journalist Clément Grandjean in Swiss Tattoo (2022, Helvetiq), the first book dedicated to tattooing in Switzerland.

Since the dawn of time

What is less well known is that people have been tattooing since the dawn of time, in Polynesia but also in the West. In fact, people have been getting tattoos since at least the end of the Neolithic period, in the Alps just 30 kilometres from the Swiss border. It was here that scientists found a mummy named Ötzi in the 1990s, the oldest known tattooed person, whose body had been preserved for thousands of years in the Austrian-Italian ice.

Ice Man Ötzi suffered from arthritis and had almost 61 lines tattooed on his body. It is assumed that their purpose was therapeutic, as the lines are placed on acupuncture points. They were probably inked point by point using a bone needle and a pigment obtained from soot.

Royalty in England and several Nordic countries liked to display Japanese dragons and naval symbols.

Clément Grandjean

The Celts, the Greeks, the Romans – the practice of tattooing was known to all Western societies long before the modern era, until the arrival of Christianity wiped it off the European map for centuries. Although research shows that the tradition persisted quietly in some circles, it was only after the arrival of the British explorer James Cook that the ink gradually spread from ships and ports to the margins of European society during the 18th century.

© Clément Grandjean

Convicts, soldiers and freaks

The tattoo was popular with soldiers in Napoleon's army (some of whom were Swiss), and with convicts and the motley array of characters who put their bodies on display in the infamous freak shows of the Victorian era. Among the Swiss, we also see this historical trend. "On the battlefields and on the high seas, Swiss people were everywhere as discreet mercenaries and skilful traders. As you can imagine, many Swiss will have seen tattoos and may even have brought them back to Switzerland, although the practice was certainly far from mainstream," says Clément Grandjean.

His book also tells us that the first typologies of tattooed people appeared in medical anthropology and criminology. The subjects of such research were the inmates of asylums, prisons and barracks, which is what gave this practice its dubious reputation. Even at this time, the tattoo was already making its appearance among the higher social classes, however. According to the book, "royalty in England and several Nordic countries liked to display Japanese dragons and naval symbols".

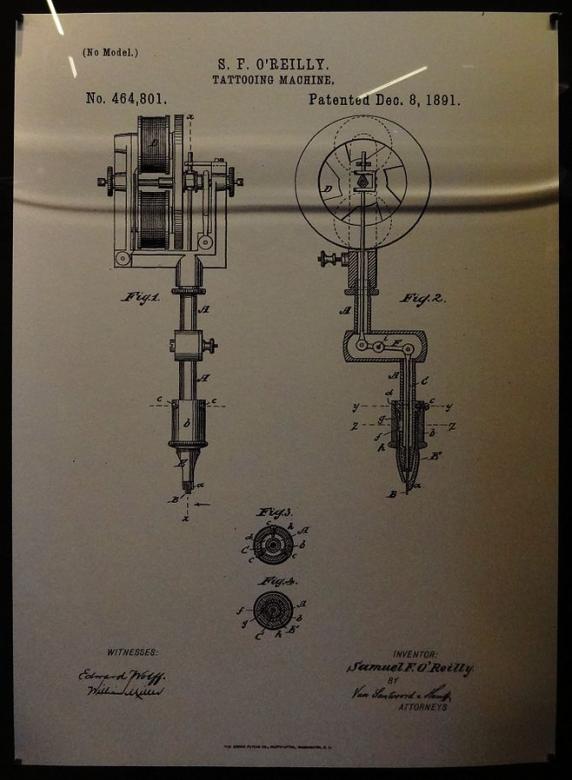

The first tattoo machine

It was not until the turn of the 20th century that the first real machine – on which many tattoo machines are based today – was invented by the American Samuel O'Reilly. This was the beginning of the professional 'tattoo artist' and ushered in the era of tattoo studios and the famous flash boards, which were at first faithful to the sailors' tradition and gradually became more personalised, bearing the inker's signature style.

The practice existed in the Switzerland of the 1900s, although there is little significant evidence apart from some pieces of skin, which the author of Swiss Tattoo came across in the Museum of Anatomy in Basel. These samples bear typically Swiss motifs: the crosier of the Basel flag, a milking scene, the allegorical figure of Helvetia, etc. Unfortunately, nothing is known about the authors or the people from whom they were taken.

Dischy, pioneer among the pioneers

The history of Swiss tattooing did not really begin until the 1950s with Dischy, who was the first artist on Swiss soil to open a parlour – still in business today – in the village of Rheineck (SG).The special know-how associated with Swiss tattooists, which lies in the perfect mastery of mechanical and aesthetic techniques and the application of ethical standards, has its origins in the Leu family saga, and in Leu's son Filip. He is seen by the profession as nothing less than the world's best tattooist, according to Clément Grandjean – and he works in Sainte-Croix.

© Clément Grandjean

Portrait image: "A fondue caquelon, the Matterhorn, gentian, a hot-air balloon and a Swiss army knife – classic Swiss motifs in a piece by David Mottier from the Rainbow Tattoo studio in Riaz © Clément Grandjean

Article originally published in Le Temps, Pauline Cancela, September 2022