A nation of railway enthusiasts: a history of the Swiss railways

Travelling over 2,000 kilometres per capita per year, the Swiss are among the world's keenest train travellers. With around 5,300 kilometres of railway lines, Switzerland has one of the most extensive railway networks in Europe. But why does this small, landlocked country have the world's densest transport network? What drove the Swiss to build railway lines at such altitudes – sometimes over 3,000 metres? Let's go back in time to find out!

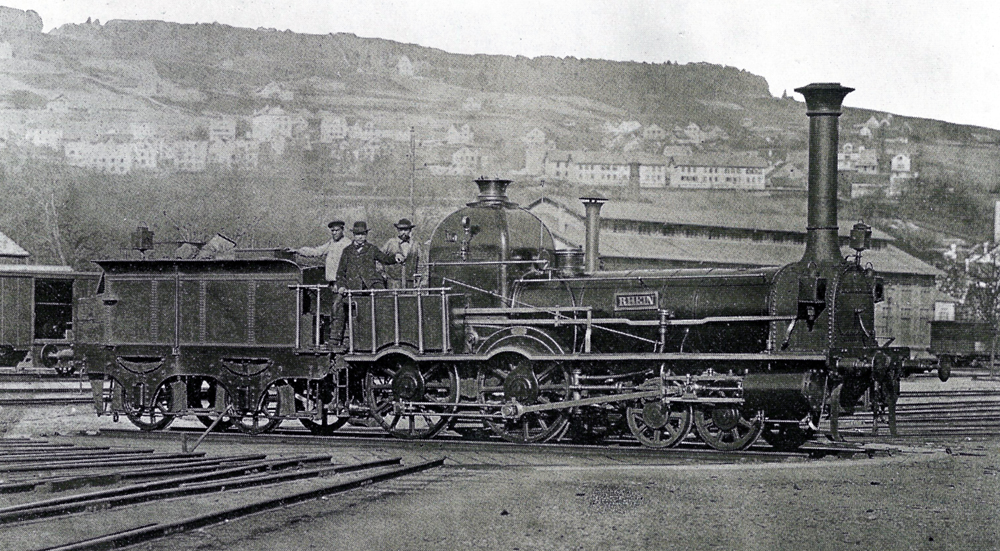

The foundation stone for the construction of the Swiss railway system was laid abroad: by the time neighbouring countries had built quite advanced railway networks, Switzerland was still largely reliant on road traffic. The Strasbourg–Basel Railway Company set the ball rolling in 1844 by building a railway line from Strasbourg in Alsace to Basel. This spurred the Swiss to try to catch up. The first plans to build railways in Switzerland had already been made in the 1820s. Negotiations dragged on for over 25 years because of political instability and the cantons' conflicting interests. Merchants who saw in railways a means to transport goods at lower cost supported the project, while local trades- and businessmen who worried about competition from cheaper products brought in from other regions opposed it. The merchant lobby prevailed: the first rail line built exclusively on Swiss territory, the Swiss Northern Railway between Zurich and Baden, was opened in 1847. It was popularly known as the 'Spanish Bun Railway' (Spanisch-Brötli-Bahn), because Spanish buns from Baden's bakeries were a highly prized delicacy in Zurich.

In the 1820s, while the first railway lines were being built in the UK, and soon after in France and Germany, the focus in Switzerland was still on waterways. Ships were the most convenient mode of transport here – for goods and for passengers. Plans for railway infrastructure were already under way, but the national political institutions needed to drive forward railway construction were lacking. It was not until 1844, with the opening of the French line from Strasbourg to the Swiss border in Basel, that the country first came into contact with actual railways. This did not however spark any sudden construction frenzy at the time. Not until a further three years later (1847) was the first railway line inaugurated on exclusively Swiss soil: the Northern Railway line from Zurich to Baden – better known as the 'Spanisch-Brötli-Bahn', named after a Spanish pastry popular in the region at the time. A beacon of hope, certainly, but the northern railway remained the only railway line in the country for years to come.

It took another five years before the Federal Railway Act of 1852 set off a railway building boom. Suddenly railway companies shot up all over the country. The Federal Act on the Construction and Operation of Railways on the Territory of the Swiss Confederation (1852) enabled private companies to build railway lines and stations and operate them. The cantons were responsible for issuing the licences, as the federal government's scope for intervention at the time was limited to matters of national defence.

Throughout the country, new railway connections and stations were now built wherever it made economic sense. Thanks to the railways, the distribution of goods became much more efficient and therefore cheaper. Traffic hubs such as those in Zurich and Winterthur emerged. Even smaller towns such as Olten saw an undreamt-of gain in importance thanks to the railways. The rail network came to mark the divide between the nation's economic and social heartland and the periphery. And by 1860, just eight years after Parliament's landmark decision, Switzerland was already the country with the densest rail network in Europe.

Switzerland's biggest construction site: the Gotthard Railway

Meanwhile, much discussion was going on over the planned route to link northern and southern Switzerland by rail: abroad, construction of the first Alpine railways was forging ahead at Semmering and through the Mont-Cenis Pass, but in Switzerland people were still arguing over which route to settle on. After all, in addition to the Gotthard, the Lukmanier, Simplon and Great St Bernard passes were also possible contenders for a transalpine route. The danger of Switzerland being bypassed altogether grew steadily from the mid-19th century, and so the Alpine transit question became ever more urgent.

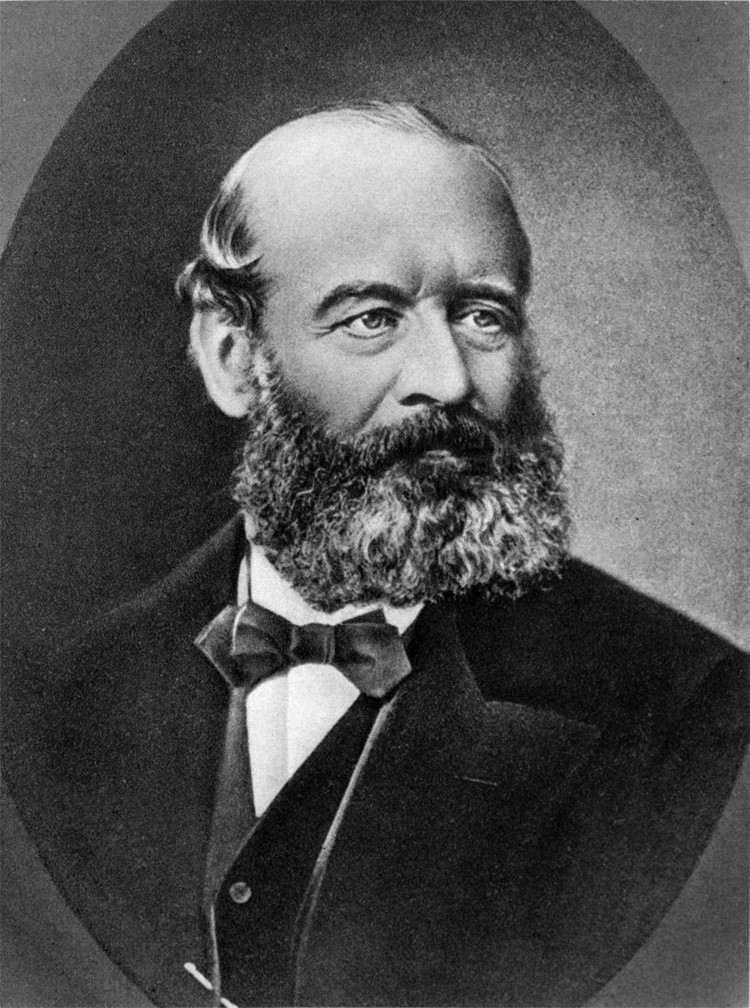

Although the Zurich politician and business leader Alfred Escher, chairman of the Swiss North-Eastern Railway, initially advocated the Lukmanier variant, in the end he came down in favour of the Gotthard line. On his initiative, two major railway companies and 16 cantons joined forces on 7 August 1863 to form the 'Gotthard Railway Association'. In the years that followed, Escher put his full economic weight behind the Gotthard project. With tireless dedication he conducted negotiations and searched for investors. His efforts bore fruit: of the total estimated construction costs of CHF 187 million for the Gotthard Railway, an international consortium covered the greater part (CHF 102 million). In addition to these funds raised on the capital markets, substantial commitments were made by the two major Swiss railway companies – the Swiss North-Eastern Railway Company and the Swiss Central Railway – and state subsidies were provided by Germany and Italy. Swiss cantons and communes also lent financial support. The federal government initially did not participate.

Agreement was also reached on the route: A 206km railway line was to be built from Immensee (northeast of Lucerne) to Chiasso. The core of this planned section was a mountain railway (Erstfeld–Biasca) that climbed through the two Alpine valleys on either side and a tunnel at the summit at over 1,100 metres above sea level. Soon the contracts were signed and sealed. In 1871 the Gotthard Railway Company was founded, Alfred Escher was made chairman of the company board and in 1872 the Genevan Louis Favre's company was awarded the contract for the construction of the large tunnel (Airolo–Göschenen).

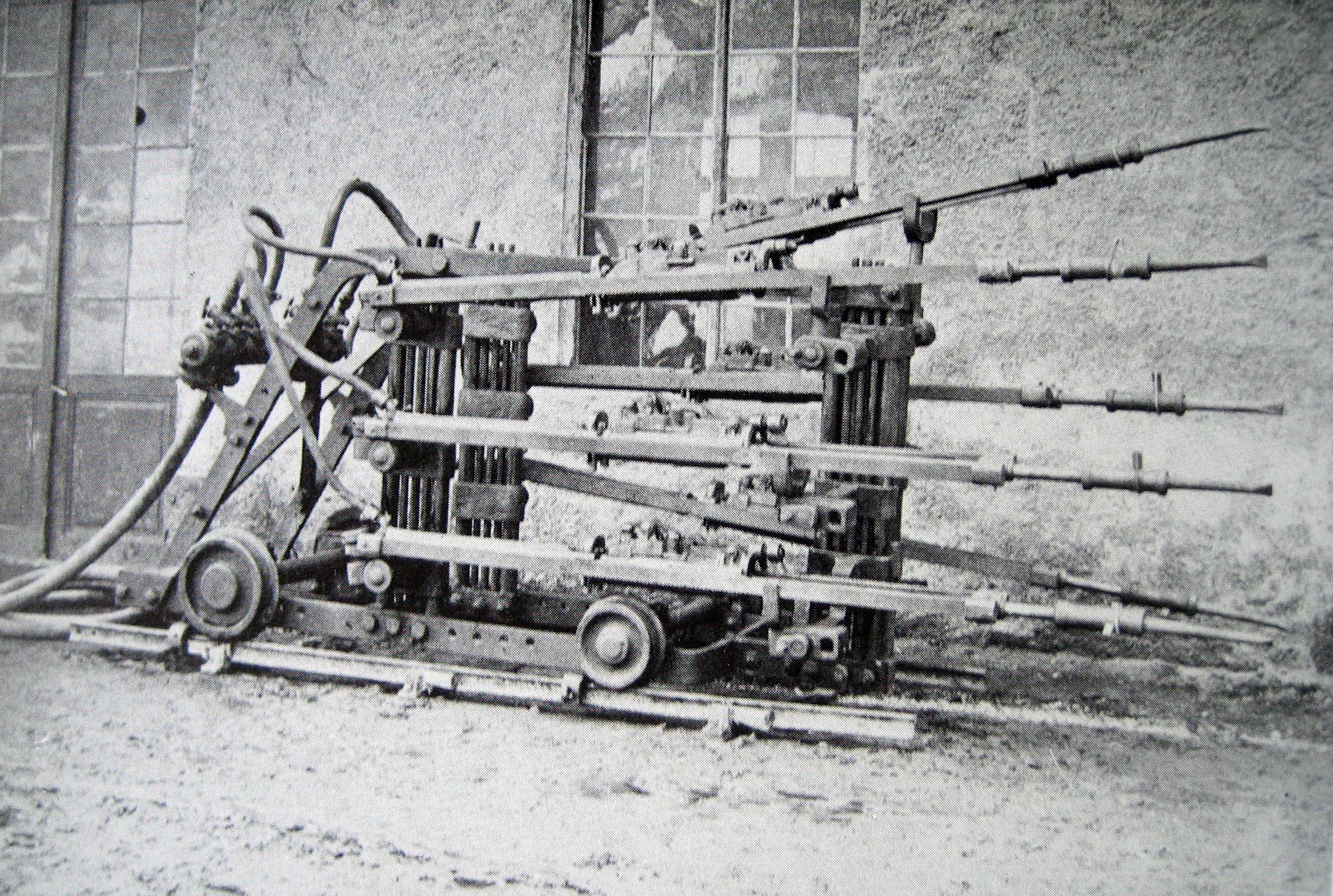

The 'Gotthard Railway' project was a huge undertaking that presented enormous challenges in many respects. Favre had undertaken to complete the large tunnel in just eight years. This was ambitious to say the least – especially considering the circumstances: Scientific knowledge at the time did not allow the geological conditions to be determined in advance with sufficient accuracy. Moreover, construction engineering was still in its early days, and the Gotthard granite posed a particular challenge. Never before had such a construction project been undertaken in the Alps, but Favre was willing to take the risk in charting this new territory.

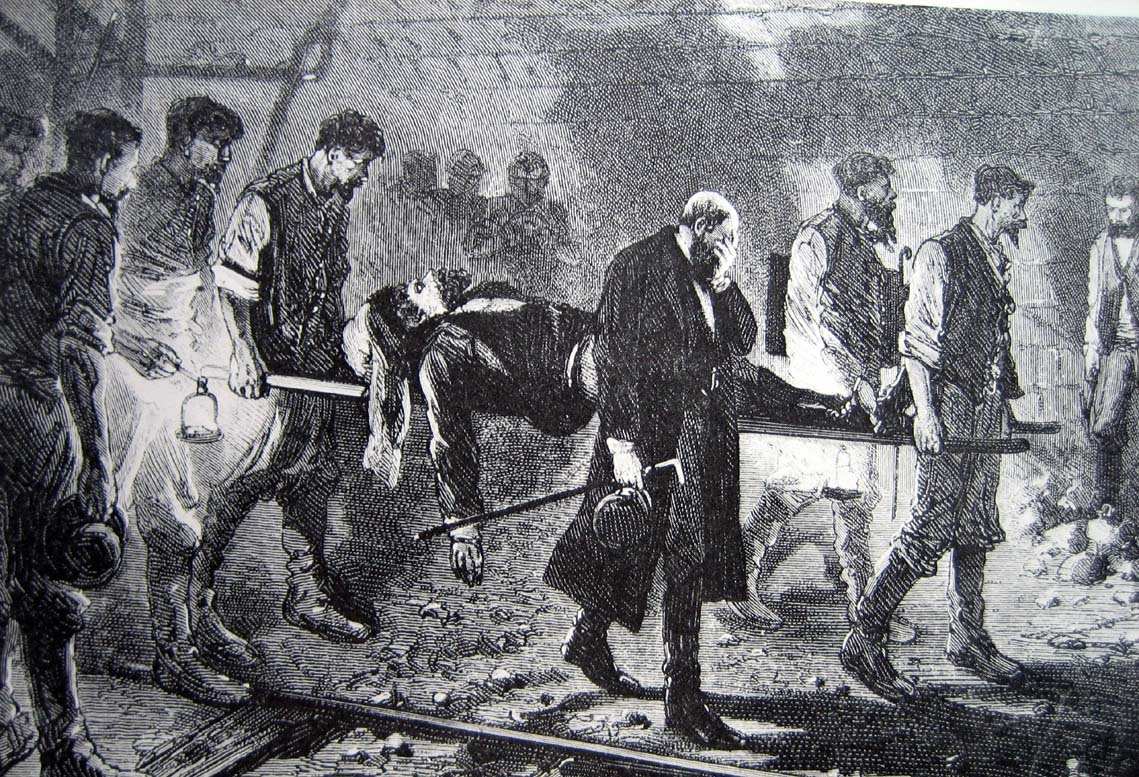

In addition to the time pressure, there were difficult working conditions to contend with: temperatures of up to 40°C inside the tunnel, unstable rock strata, inadequate ventilation, and dynamite fumes that caused eye and respiratory tract diseases. Fatal accidents occurred, with almost 200 workers in total losing their lives on the construction sites in Airolo and Göschenen. And an additional 150 men died from illness. The difficult working environment and generally appalling sanitary conditions also led to strikes.

The project fell ever further behind schedule, driving up the costs. Tensions between Favre and the Gotthard Railway Company and the new critical cost estimate (CHF 102 million, 1876) by chief engineer Konrad Wilhelm Hellwag led to turbulence on the stock market. Gotthard Railway bonds dropped in value and even the completion of construction was called into question. As it turned out, however, Hellwag's forecasts were exaggerated, with detailed calculations showing an actual additional capital requirement of around CHF 40 million. Thanks to cash injections from Italy (10 million), Germany (10 million), and the first modest subsidy from the federal government (4.5 million), as well as private investment, the Gotthard Railway could finally be completed.

The world's longest railway tunnel

Louis Favre never got to witness the moment when workmen from the Swiss and Italian sides broke through the final barrier of rock: he had died of a heart attack while inspecting the tunnel the previous year. But the workmen found a way for him to be the first to cross the tunnel nonetheless. When the borers drilled through the final layer of rock on 28 February 1880, the workmen passed a tin containing a photograph of Louis Favre through the breach. It was their way of celebrating this historic breakthrough and paying tribute to the engineer who had led their work. The tunnel's horizontal alignment was out by only about 30 centimetres and by 5 centimetres on the vertical. In engineering and surveying terms, it was nothing short of a miracle for the time. They had built the world's longest railway tunnel (15 kilometres). The Gotthard Tunnel's grand opening in 1882 made headlines around the world as a great feat of engineering by the small Alpine nation. During the more than 130 years between the opening of the original Gotthard Tunnel and the completion of the 57-kilometre Gotthard Base Tunnel in 2016, the old Gotthard line with its famous tunnel played an extremely important role in European passenger and freight transport. A piece of Swiss railway history that was considered to be one of the wonders of the world.

The Jungfrau Railway: Europe's highest railway station

Swiss railway pioneers had a long-cherished ambition of building a railway line to the 4,158m summit of the Jungfrau. The challenge was enormous, as the route to the summit was made impassable by year-round ice and snow. But in 1811 the brothers Hieronymus and Johann Rudolf Meyer and mountain guides Alois Volken and Joseph Bortis completed the momentous first ascent, shattering the myth that the Jungfrau was invincible. Perhaps it was this success that prompted them to attempt other four-thousand-metre peaks. This abiding fascination with scaling the majestic mountains of the Alps took on further, larger dimensions in the second half of the 19th century, when people started talking of making even high mountain peaks accessible by train – including the Jungfrau. At least that was the plan.

"Now I've got it!" exclaimed Adolf Guyer-Zeller one Sunday in 1893 to his daughter, as he spied the Wengernalpbahn train travelling up to the Kleine Scheidegg. That night he sketched his idea on a sheet of paper: building a railway from Kleine Scheidegg to the Jungfrau.

The building of Europe's highest railway station

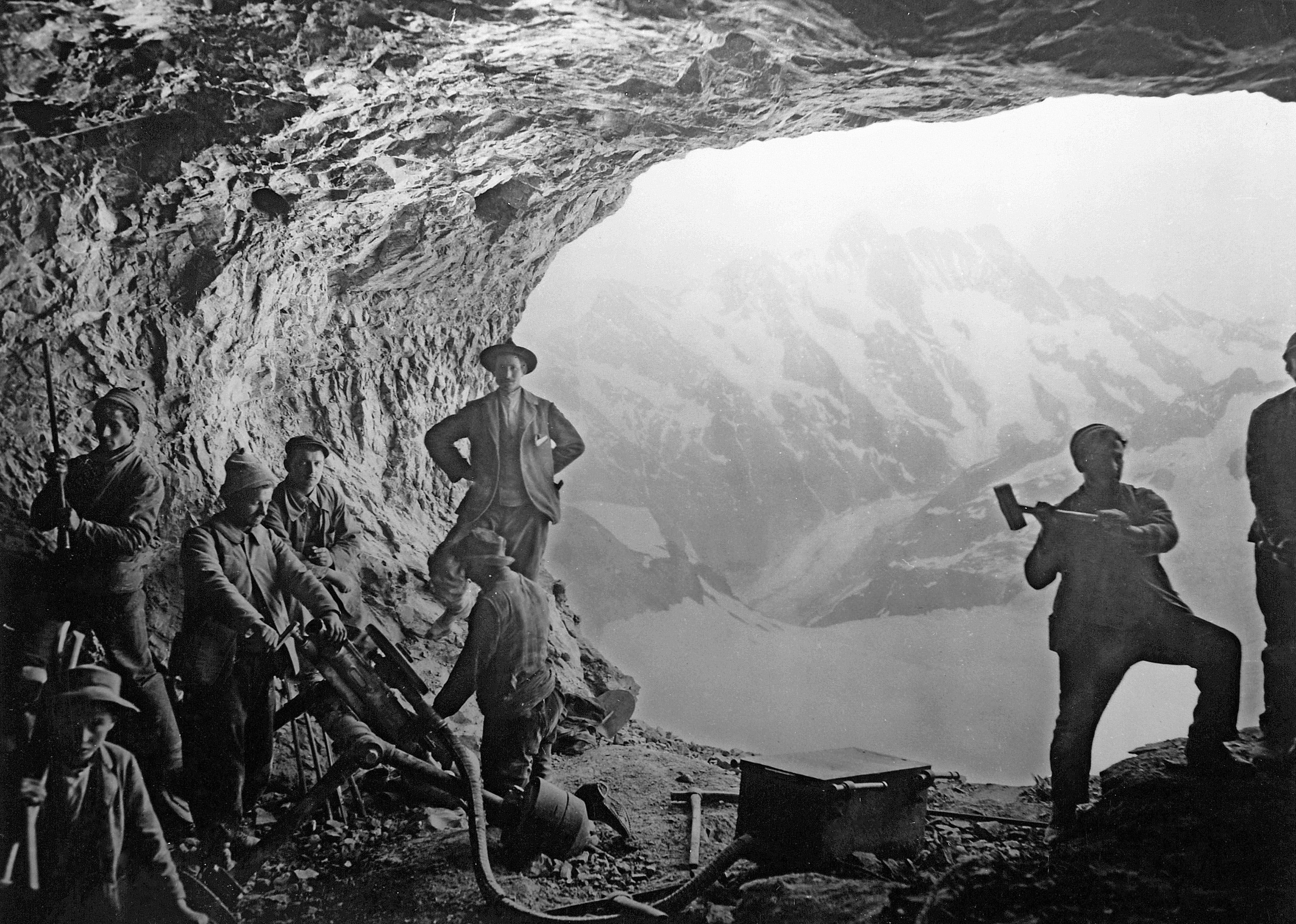

Just under four months after that auspicious Sunday walk, Guyer-Zeller submitted a licence application to the Federal Council. The ground-breaking ceremony took place on 27 July 1896. It took 24 long months of arduous labour – not three, as originally planned – to complete the first section. The delay was in hindsight hardly surprising, considering that the tools available were mostly just shovels and pickaxes. No machinery, just muscle power.

The death of Guyer-Zeller in 1899 was a tragic setback. At that point, the continued construction of the Jungfrau Railway appeared to be in question. But Guyer-Zeller's heirs were determined to continue his work. Securing funds to continue the work proved difficult, the rock face resisted every hammer strike, and the labourers worked under extremely hard conditions. Work progressed slowly. The management ultimately decided to rework the original plan to build a railway line all the way to the Jungfrau summit and redesignated the Jungfraujoch, at an altitude of 3,454m, as the new terminus of the Jungfrau Railway.

In 1912, 16 years after work began, a festooned train carrying a group of passengers invited especially for the occasion made its maiden journey up to the Jungfraujoch – Europe's highest railway station. The information boards and commemorative plaques displayed there still bear witness to the feat of engineering achieved at altitudes above 3,500m by the men who built the railway over 100 years ago.

The journey into the 20th century

Even in the early years of private railway construction, there were calls for the railways to be nationalised. Indeed, the 'buy-back' question preoccupied federal politics for some time. Then, in 1883, the possibility of rescinding the licences of most railway companies presented itself. But it took a long time for the Swiss people to actually vote in favour. Not until 20 February 1898 did they finally give a resounding "yes" to renationalisation: the Swiss railways for the Swiss people, went the campaign slogan at the time. Thus were the foundations laid for the Swiss Federal Railways (SBB), known in English by their German, French or Italian initials SBB, CFF or FFS. The SBB began operating in 1902. Four of the five main railways were nationalised, namely the Central Railway, the Nord-Eastern Railway, the Jura–Simplon Railway and the United Swiss Railways. The Gotthard Railway followed in 1909.

Switzerland was an early pioneer in the electrification of railway lines. Coal for steam engines was in short supply during the First World War. When the Second World War broke out, renewed coal shortages prompted the large-scale electrification of the SBB network. Rail electrification continued apace after the war. The last SBB steam locomotive was retired in 1967. Since then, the entire Swiss railway network has been powered solely by electricity – the first of its kind.

Swiss railway clock

A minute is a unit of time of 58.5 seconds – in Swiss railway stations. Why? In 1944 Hans Hilfiker, an SBB engineer, developed what would come to be known as the Swiss railway clock. Passengers rely on these clocks, which are prominently placed in every Swiss railway station to this day. As Hilfiker said at the time: "punctuality is the railways' trademark." The problem was, however, that Swiss railway station clocks were not synchronised and therefore did not necessarily show the same time. Hilfiker set himself the challenge of solving the problem. In 1943, he began testing a clock with a red second hand in Zurich's main railway station. It was driven by an electric motor and completed each revolution in 58.5 seconds. It then paused briefly before starting its next revolution, synchronised with the minute hand of the master clock. Introduced in 1944, the system is still in place today: Swiss railway station clocks all receive a time signal every minute from a master clock, enabling them to stay synchronised. Time and rail in perfect harmony.

The regular-interval timetable

In the second half of the 20th century, the regular-interval timetable began to be introduced in the Swiss railway network. Under a regular-interval timetable, trains arrive and depart each station at the same minute after every hour or half hour, guaranteeing regular, recurring connection times. Experts had long argued that a nationwide regular-interval timetable, like the one that had been in place in the Netherlands since 1934, was not feasible for Switzerland. But history would prove the experts wrong: Samuel Stähli, a Bernese civil engineer and railway buff, founded the 'Spinnerclub', a group of railway enthusiasts who met every Monday evening to try to devise a regular-interval timetable for the entire Swiss railway network. They dispensed with conventional graphical timetables and decided to draw up a regular-interval timetable based on topographic network maps. The concept worked: in March 1969 they submitted a 19-page report on their timetable, which they presented at a professional symposium in 1972. They won over the SBB management, which set up a larger working group to develop a more detailed timetable that would be put into daily service. In 1982, the SBB announced: "Your timetable is our timetable – your SBB". Since then, Swiss trains have departed at least once an hour for destinations across the length and breadth of the country. The introduction of the regular-interval timetable brought an extraordinary expansion of railway services.

At the beginning of the 1980s, in addition to the introduction of the regular-interval timetable a further milestone was achieved in Swiss public transport: After rejecting two bills (an underground rail bill in 1962, and an underground and suburban rail bill in 1973), which were intended to solve the problem of rising traffic volumes due to population growth in the Zurich area, the people of Zurich voted decisively to accept a suburban railways bill on 29 November 1981, with a staggering 74% in favour. The core of the suburban rail (S-Bahn) proposal was the extension of SBB facilities and required, among other things, the construction of a multi-track through station under Zurich main station, an extension of Stadelhofen station and a new station at Stettbach, at the north portal of the Zurichberg tunnel.

The Rail 2000 project

Rail 2000 is without a doubt the largest Swiss railway project of modern times. The Swiss electorate endorsed the project in 1987, firing the starting shot for 130 construction projects. Rail 2000 is designed to reduce travel times between all of Switzerland's hub stations to just under one hour. Trains leave the main stations just after the hour and the half hour to reach their destinations at other hubs just before the hour or half hour, with the main stations functioning as 'transport spiders' in a complex system of railway hubs. This ensures well-coordinated rail connections and shorter waiting times between trains. The stated aim of Rail 2000 was to make trains more frequent, faster and more comfortable. The project led to more direct connections between stations and higher speeds throughout the rail network. Countless railway lines were upgraded or newly built, reducing travel times to under an hour on the main routes. The new Rail 2030 project aims to add new hubs, continuously reduce travel times and increase passenger capacities. In 1958, the SBB began advertising its services with the slogan 'those with brains take the train' – which is as true today as it was then.

For more detailed insight into the history of the Swiss railways, we recommend a book by Joseph Jung, published in 2019 (available in German only): 'Das Laboratorium des Fortschritts. Die Schweiz im 19. Jahrhundert' (The laboratory of progress: Switzerland in the 19th century), (Verlag NZZ Libro, 2. Auflage 2020). Containing some previously unpublished pictures, the book offers 678 pages of fascinating insights into this small Alpine country. It served as a source for this article.