Paul Klee's universe of images and his work in Bern

Known for his magical imagery and dream-like worlds, Paul Klee was a world-class painter and one of the most important artists of the 20th century. He was a member of the Der Blaue Reiter movement and later taught at the Bauhaus in Weimar and Dessau. Although Klee spent more than half his life in Bern and is often referred to as a Swiss artist, he was in fact a German citizen all his life.

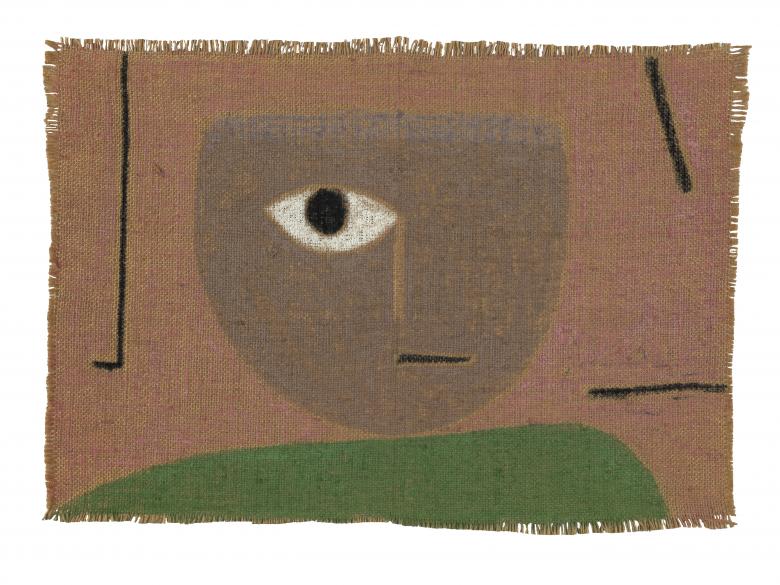

With his angels and machines, shiny cities and flying fish, and his enigmatic faces and artistes' bodies, Paul Klee is indelibly inscribed in our collective conscience. As a unique fusion of the abstract and the figurative, his art gives visual form to spiritual worlds.

Klee's cosmos

His oeuvre is simply a visual encyclopaedia of "all the beauties and horrors of our world, its fears, hopes and desires, life and death, all things first and last," wrote art historians and curators Dieter Scholz and Christina Thomson.

Klee's motifs became hugely popular in the post-war period, often as cheerful, playful and poetic reproductions on postcards and calendar pages. But it would be a gross misinterpretation to view his work in such simplistic terms. There is always at least one hidden layer to Klee's art:

I believe that whoever understood enough to be able to read all of Klee's symbols would see all of the horror of our degenerate time beneath the so intensely pleasurable surface of these images,

wrote Georg Schmidt, the director of the Kunstmuseum Basel, in 1935.

Motifs of Bern: 'Quarry' and 'Landscape of an exotic river'

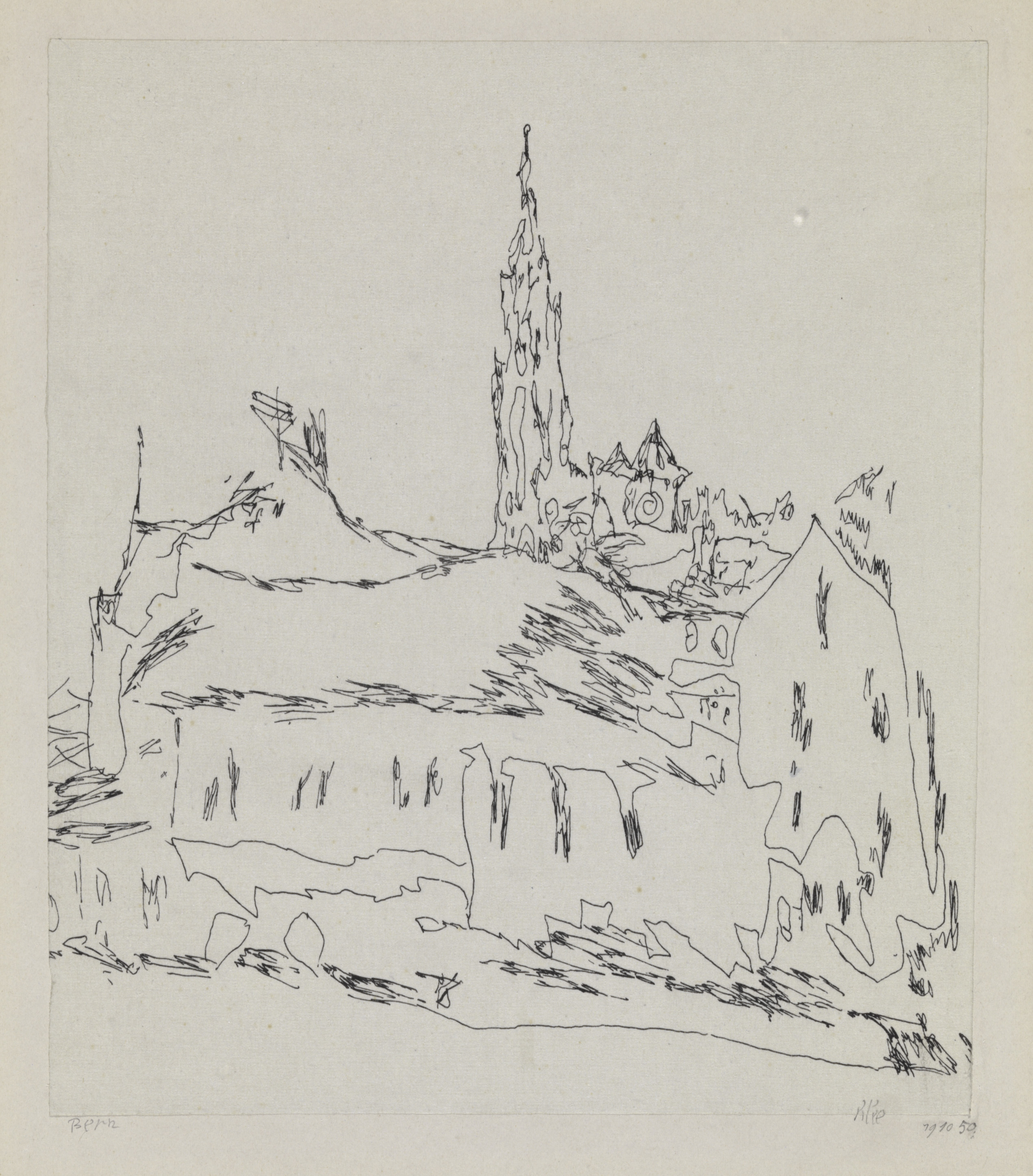

Paul Klee was born on 18 December 1879 in Münchenbuchsee, in the canton of Bern. His mother was a Swiss singer, his father a music teacher from Germany. Klee spent his childhood and youth in Bern. Academically he went from mediocre to poor – but he was a talented violinist and for a time he pondered over whether to make music or painting his profession. In his early sketchbooks he drew the Aare floodplain as well as the Zytglogge tower, Bern Minster and various views of the Matte district. Even then he was experimenting with distortion and alienation.

Munich: capital of art

But Klee was no longer content to stay in the Swiss capital. "Bern is fine if I wanted to be a bookworm or a schoolmaster, but certainly not an artist," he wrote as a 19-year-old to his father. And so, Klee swapped the provincial life for a cosmopolitan city of art: Munich. Here he finished his training and got to know a group of artists calling themselves Der Blaue Reiter: August Macke, Franz Marc and Wassily Kandinsky. And it was here he met and fell in love with the pianist Lily Stumpf. They married in 1906 and their son Felix was born in 1907. The division of roles in the Klee household was somewhat unusual for the time: Lily was the breadwinner, working as a pianist and piano teacher, while Klee looked after their son and the home, even setting up a makeshift studio in the kitchen!

Fame and exile

1914 was a turning point in Klee's artistic career, when he travelled to Tunisia with August Macke and Louis Moilliet. At the end of the trip, for the first time ever he felt he had mastered the full range of colours on his palette: "I am an artist". The First World War broke out immediately afterwards, and both August Macke and Franz Marc died in battle. Klee was also called up but escaped the same fate as his friends.

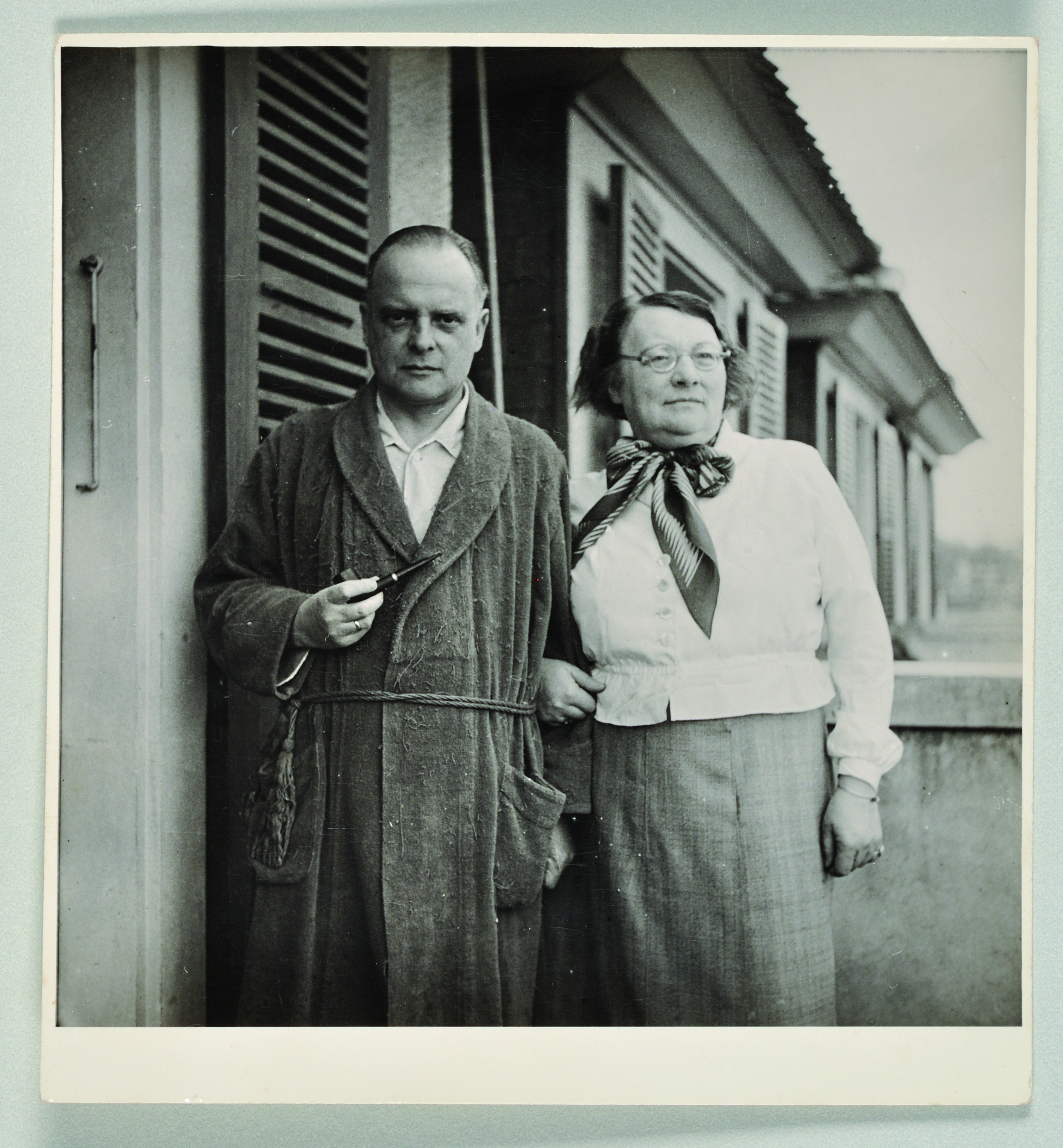

The 1920s brought him the breakthrough he sought – not only artistically but also in social status – when he was appointed a teacher, or 'master', at the Bauhaus school in Weimar and later also in Dessau. There he lived in a splendid Masters' House, with Kandinsky his neighbour. In 1931 he was asked to join the Kunst-Akademie in Düsseldorf. Klee's success in Germany was short-lived, however. In the Nazi party's 'Degenerate Art' exhibition touring the country, Klee was among those artists whose work was labelled 'degenerate' and his licence to teach was revoked. Together with Lily, he decided to emigrate to Switzerland.

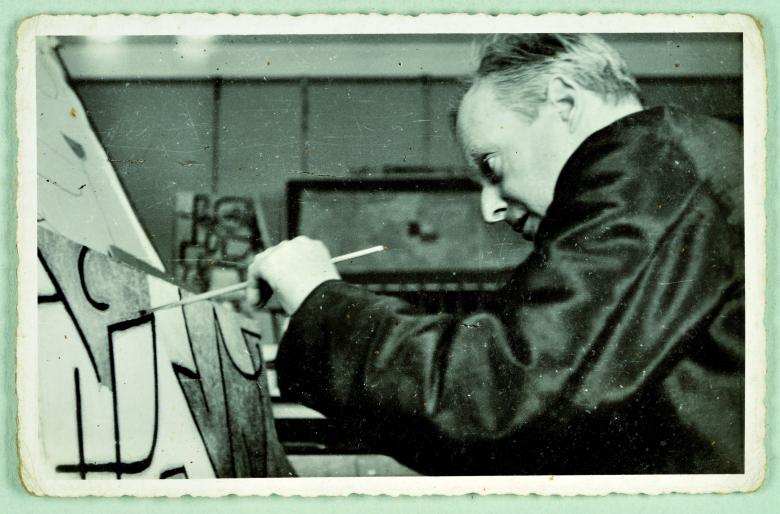

His final studio

It was in Bern's Elfenau district where Klee produced his most famous latter works – some 3,000 paintings – in the living room of a small but bright three-room apartment at no. 6 Kistlerweg. The painting utensils he left and the paintings themselves show signs of some of Klee's more revolutionary techniques: for example, he painted over and cut up his pictures, built them up over several layers, scraping with his spatula. And he wasn't too proud to transport his paintings in the potato sacks he got from local farmers.

Such tremendous creative power can only be admired, given that he was working under doubly difficult conditions: as an expelled, ostracised artist but also as a terminally ill man. Klee's long, quiet suffering began in 1935 with the onset of scleroderma. This very rare wasting disease caused him excruciating pain in the last years of his life, and still he went about his daily business with dignity, without complaint. In the end, his oesophagus had tightened so much he could eat only soft food. He was quickly out of breath and used to call the short hill up to his apartment his 'Matterhorn'.

Paul Klee passed away on 29 June 1940 during a stay at a sanatorium in Locarno. He had spent over half his life in Switzerland – a total of 33 years. Yet, he had been born a foreigner in Switzerland and died a foreigner, despite several attempts to obtain Swiss citizenship. Even the day before he died, Klee again made one final attempt, dictating from his bedside a letter to be sent to the naturalisation authorities in Bern. Just a few days later he probably would have received the long-awaited document.

An even greater gift, however, is the fact that the world's largest collection of Klee's art is now housed in Bern, at the Zentrum Paul Klee designed by Renzo Piano and opened in 2005. This is largely thanks to four collectors in Bern and Klee's son Felix, who together managed the estate.

The centre is close to Klee's final resting place at Schosshalden Cemetery. The epitaph on his gravestone (which Klee himself wrote in 1920) speaks quite assuredly of other worlds, of the kind inimitably also found in Klee's art:

I cannot be grasped in the here and now. For my dwelling place is as much among the dead as the yet unborn. Slightly closer to the heart of creation than usual. But not nearly close enough.