The second life of Swiss bunkers

There are believed to be more than 8,000 of them, dotted all over Switzerland, some still concealed beneath their camouflage of yesteryear. But now the country's bunkers have come back to life as veritable national curiosities.

Vestiges from the Second World War and the nuclear crisis of the Cold War, the purpose behind these bunkers has fluctuated over the years. But the stories surrounding the bunkers continue to fascinate budding explorers and large swathes of tourists. And they continue to surprise local residents too, seeming to appear out of nowhere thanks to their remarkable capacity for concealment – whether in the natural or urban jungle. But don't think that these blocks of reinforced con-crete are simply hibernating. In the last fifty years, they have been put to a wide range of uses: from original hotels and cheese cellars to data centres, museums and even a mushroom factory.

The myth of the cave, almost

"Underground: the places where the Swiss store memories, myths and a part of their identity" states geographer André Ourednik in the Swiss research magazine horizons. Everyone has heard of Switzerland's major alpine works – like the Gotthard railway tunnel, the longest in the world – a veritable "know-how to export". We also know just how important wine cellars are in Swiss folklore. Less well-known is the Swiss National Redoubt, drawn up by the authorities in the 1940s to buttress the Alps with bunkers and fortifications in order to prevent foreign invasion of a country surrounded by the Axis powers. Likewise, the 360,000 bomb shelters (mainly to protect the Swiss population) that became a compulsory feature of any new building since the Cold War, are largely unknown to the general public.

The bunker 2.0

These shelters, however, were usually empty and unused. Because of major maintenance costs, the Swiss army began selling around twenty each year to the highest bidder. It is not involved in how the bunkers are re-used. The bunkers have elicited the interest of researchers, philosophers, photographers, architects and artists to varying degrees. In exploring these relics, they have documented, exhibited, transformed and even reinterpreted Switzerland's bunkers, both fascinated and repulsed by them at the same time ('bunker villa' is commonly used in French to refer to an imposing but unsophisticated house). Let us consider for a moment those artists that have helped us to better understand these blocks of concrete in our society today.

The photojournalist: Arnd Wiegmann

An avid fan of the great North American photographer W. Eugene Smith, Arnd Wiegmann (born in 1961) started out in the business in Cologne before joining the German edition of Reuters. Wiegmann still works for the press agency but is now based in Zurich, from where he travels the length and breadth of Switzerland to "portray the myriad facets of Swiss society", notably with a few Swiss Press Awards in his pocket. His photo-reportage on Switzerland's recycled decommissioned bunkers was shown around the world in 2016 – from the 17-room La Claustra hotel buried in the Gotthard Massif, the Fuchsegg fortress on the Furka Pass, the mushroom factory in Erstfeld and the Giswil cheese dairy to a data centre so large it would have been able to contain over a thousand soldiers. Wiegmann's work has done a great deal to raise the visibility of Switzerland's bunkers internationally.

Architectural reappropriations

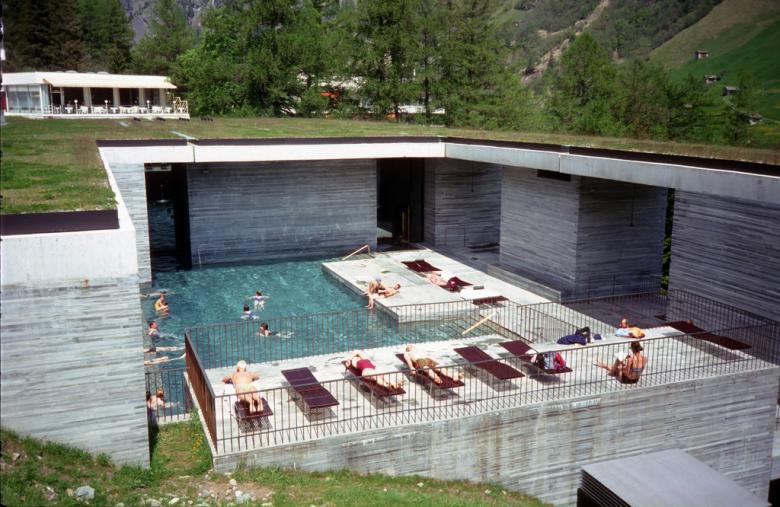

While the thermal baths of Vals, designed by Peter Zumthor, are undoubtedly the most famous work of art in Graubünden, the canton conceals many architectural wonders that belong to the minimalist aesthetic, conveyed in part by the bunkers and other Brutalist creations – such as the Atelier Bardill created by Valerio Olgiati, Lord Norman Foster's Chesa Futura, Arosa Wellness designed by Mario Botta and Haus Presenhuber of Fuhrimann and Hächler. Published by architect Hans-Jörg Ruch, the book Historic Houses in the Engadin: Architectural Interventions (published by Steidl in 2006) is considered to be a pioneering work. On the Andermatt side, a new concert hall is being designed in an old bunker attached to a larger building complex by London-based Studio Seilern Architects. But don't think Switzerland is the only refuge for these refined, concrete constructions – just type #bunker to see how successful this style is!

Amy O'Neill's reappropriations

In 2003 at the MAMCO in Geneva , the North American artist showcased her bunker replica adorned with psychedelic fluorescent images and kitted out with the regulation equipment – a space that "looked inhabited and... [gave] the impression that it would provide adequate protection in the event of a nuclear accident". Directing her scathing irony first and foremost at the vernacular culture in the US, O'Neill (born in 1971) hijacked the aesthetics of these protected spaces by combining two different milieus – the hippies and the survivalists. Fifteen years after the creation of this installation, there is no end to the number of major doomsday projects all over the world... Echoing O'Neill's work, in 2010 MAMCO also displayed the photo exhibition 'Insite', a series of photographs of underground hospitals taken by the Swiss artist Maud Faessler (born in 1980). The work depicts a "universe built to protect people from their fellow human beings, but from which they themselves are also absent" in the words of Christian Bernard. A universe where humans shine by their absence... until, that is, these architectural ruins are transformed into tourist attractions or facilities for production!