Tour Switzerland through 20 works of art

Switzerland’s bucolic landscapes may have inspired a thousand paintings, but the country’s lively art scene and creative spirit are not limited to these alone. Take a short tour of Switzerland through 20 representative works, from Ferdinand Hodler to Renée Levi.

The Miraculous Draft of Fishes, by Konrad Witz (1444), housed in the collections of the Geneva Museum of Art and History, is generally considered to be the first painted landscape in Western art history. In the distance, from left to right, it shows the Voirons, Môle, Mont-Blanc and Petit Salève mountains; in the middle ground is the expanse of Lake Geneva, its banks far less populous than they are today.

Some historians have wondered (as did Dominique Radrizzani in Lemancolia, his captivating artistic treatise of Switzerland) whether Van Eyck’s Crucifixion, a panel painting completed some 15 years earlier, might merit the first landscape title rather than Witz’s work. Van Eyck’s painting, too, is a Swiss landscape: the winding Rhône and the familiar peak of the Catogne can be seen in the background. Indeed, Switzerland has always maintained a distinctive relationship with its landscapes, which have been painted, engraved, photographed and captured in verse or song many times over and are invariably celebrated for their beauty.

This list, which is necessarily too short, is not meant to be an exhaustive guide to Swiss art and culture. Rather, it is an attempt to illustrate how Swiss artists, from the historical avant-garde through to today, have continually struggled with landscape imagery and its ponderous legacy, the burden of the beautiful. This struggle has taken many forms: emigrating to other parts of the world, countering depictions of overly touristic sites with radical abstraction, replacing the solemn contemplation of nature with dark humour and scathing sarcasm, drawing on the resources of the science fiction, pop art or punk movements – or provocatively choosing to focus on the technical, urban and modern instead of on tranquil pastoral scenes.

Meret Oppenheim, Fountain, 1983 (Nägeligasse, Bern)

Although it took many years for Meret Oppenheim’s famous fountain to be accepted by the residents of Switzerland’s capital city, the bulky limestone deposits and mosses that grow chaotically over the grey spirals are no longer a source of controversy. Close to fifty years after the fountain’s inauguration, these shapes, which change with the seasons, are a true celebration of biological life and a powerful environmental allegory.

Peter Fischli et David Weiss, The Right Way, 1983

In this work in the form of a story, the two artists travel through Switzerland wearing stuffed rat and bear costumes. They traverse idyllic landscapes, ponder great philosophical questions and embark on adventures in which humans remain absent. Although the film parodies the trope of the solitary wanderer and his reveries, it takes seriously the core questions of the Romantic movement, particularly regarding man’s relationship with nature. This mixture of levity and gravitas remains the duo’s trademark – a technique that American filmmaker John Waters praised enthusiastically.

Max Bill, Pavilion Sculpture, 1983 (Bahnhofstrasse, Zurich)

Painter, designer, architect, editor, curator, teacher, politician: Max Bill was a man of lifelong powerful convictions. His granite pavilion sculpture, located on a busy street in downtown Zurich, stands as an example of his ambition to profoundly transform daily life through geometric language. Bill, whom Harald Szeeman described in 1969 as “a figurehead of Swiss cultural life”, continues to embody a certain idea of Swiss art even today.

Pipilotti Rist, Ever Is Over All, 1997

In one of Pipillotti Rist’s first large-scale video installations, we see a young woman resembling Snow White walking down a deserted street. Far from evincing Disney-esque innocence, however, she is joyfully smashing the windows of the cars she passes, a smile on her face. This dream-punk masterpiece, a copy of which is included in the MoMA collection, has had a lasting cultural impact. One can even see it echoed in the music videos of Beyoncé, who drew direct inspiration from this work in Hold Up.

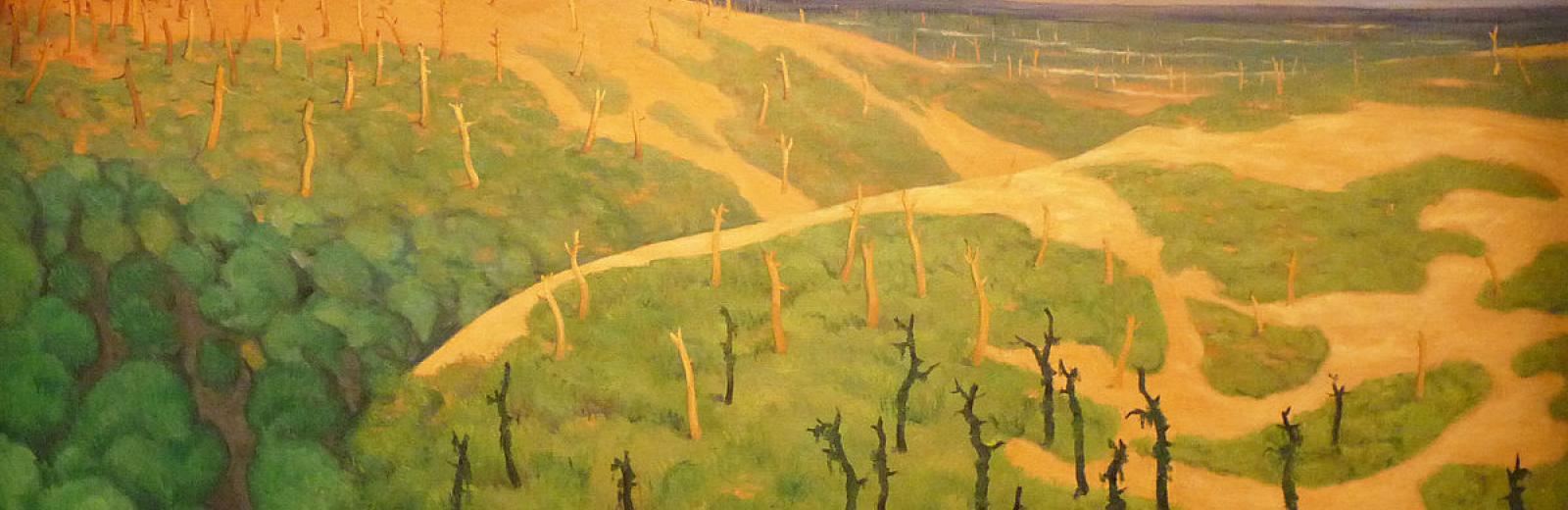

Félix Vallotton, The Gruerie Forest and the Meurissons Ravine, 1917

Orange, green, yellow: the decorative quality and bold Nabi-esque colours of this late-period painting contrast strangely with its gloomy subject, a landscape from the First World War. Vallotton, the most Parisian of Swiss artists, emigrated to France in the early 1880s and quickly joined the country’s avant-garde and anarchist movements. The horrors of war left a deep impression on him, and between 1914 and 1918 he painted a series of works that, like his Châlons Cemetery, are “the perfect expression of mathematical carnage”.

Ferdinand Hodler, Lake Geneva in Blue, 1904 (Cantonal Museum of the Fine Arts, Lausanne)

2018, the centenary of the artist’s death, was ‘the year of Hodler’: multiple exhibitions explored his work in every conceivable light. Although he painted portraits, historical scenes and strange symbolist allegories, Hodler is known internationally for his lakeside landscapes, particularly those of Lake Geneva (Lac Léman, in French). In fact, he is the most famous of the painters of ‘lémancolie’ (a French play on words referring to the sense of melancholy pervading many renderings of this body of water).

Emma Kunz, Work No. 003, no date

Emma Kunz (1892–1963) is a fascinating figure at the crossroads of art and mystical practices. Fond of describing herself as a ‘researcher’, Kunz lived in German-speaking Switzerland, where she worked as a telepath, psychic and healer. From 1938 onward, she made large drawings on graph paper that transmit her insights in coded form. These works have been rediscovered and received with enthusiasm by the art world over the past decade.

H. R. Giger, Museum Bar, 2003 (Gruyères)

Nestled deep in the sublime landscape of Switzerland’s Gruyère region lies a terrifying installation by the Swiss master of horror, Hans Ruedi Giger. Known worldwide for his work on the first Alien movie (1979), and particularly the alien itself, Giger was a prolific artist and illustrator. This bar, filled with his chilling biomechanical sculptures, is located across from the museum dedicated to him in the small town of Gruyères.

Verena Loewensberg, Untitled, 1978 (Haus Konstruktiv, Zurich)

Verena Loewensberg (1912–1986) was one of the principal members of the Concrete Art movement in Zurich. In the 1930s, she began exploring the possibilities of art governed by rational principles. However, her unique combination of systematics, extreme simplicity and dynamic movement is present even in her latest pieces. This avant-garde work is still an important source of inspiration for much of the contemporary geometric art scene, both in French-speaking Switzerland and abroad.

John Armleder, Olivier Mosset and Sylvie Fleury, AMF, 1990 (Galerie Rivolta, Lausanne)

John Armleder and Olivier Mosset were often exhibited together during the 1980s, but AMF was the first collaboration between the three artists, and Sylvie Fleury’s first public exhibition. It shows an assortment of brightly coloured shopping bags lying on the floor, bearing luxury-brand initials and still containing bought items. This pop gesture, which recalls Warhol’s boxes of laundry detergent, ushered in a blurring of the art and fashion worlds that remained an important trend throughout the 1990s and 2000s.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Composition Dada, 1920

In 1920, painter, sculptor, dancer and textile artist Sophie Taeuber (1889–1943), together with her future husband Jean Arp, became involved in Dada, a movement so often associated with Paris and Berlin that one can forget it originated in Zurich. This piece, which infuses abstract composition with a sense of dance-like movement, demonstrates Taeuber’s preference even at this early stage for the synthesis of the arts – a defining feature of the catalogue of this fiercely modern figure.

Thomas Hirschhorn, Swiss-Swiss Democracy, 2004 (Swiss Cultural Centre, Paris)

In preparatory notes written several months before the work’s opening, Hirschhorn declared his intentions to “lay siege” to the Swiss Cultural Centre in Paris. The exhibition, designed in response to Christoph Blocher’s arrival in government several months earlier, ignited a political scandal in Switzerland. Various figures spoke out against the artist and many were offended by Pro Helvetia’s support of exhibition, even though they had not seen it. But the Hirschhorn method proved to be effective both politically and artistically.

Aloïse Corbaz, Painted Lady of Montreux, 1941 (Art Brut Collection, Lausanne)

One of the essential artists of the world-renowned Art Brut Collection is Lausanne native Aloïse Corbaz (1886-1964). Corbaz threw herself headlong into drawing and painting after her return in 1918 to Switzerland after having worked several jobs as a governess in Germany, where she had met Emperor William II and fallen madly in love with him. Jean Dubuffet, the founder of the Art Brut movement, met her in 1947 and incorporated her drawings of princely figures and heroines into his collection.

Jean-François Schnyder, Corso Schnaps Parade, 2009

Train-station waiting rooms, highway views, unpretentious sunrises, kitsch chalets – or, as in this artwork, small artisanal sculptures and a parade of liquor bottles. Since the late 1960s, this Basel-born conceptual artist (1945–) has found inspiration in vernacular or banal cultural forms and mastered the art of derision. Schnyder represented Switzerland at the 1993 Venice Biennale.

Peter Stämpfli, Proud Beauty, 1963

Although Pop Art is primarily associated with England and the United States, Switzerland has also played a role in this movement defined by modern culture, consumer society and the celebration of merchandise. In the mid-1960s, Stämpfli, known today primarily for his automobile-inspired work, completed several series of paintings all based on the same model: a white background and an oversized object painted in the plain colours of an advertisement.

Franz Gertsch, Medici, 1971–1972

In 1969, when he was almost forty years old, Bernese painter and engraver Franz Gertsch had a revelation during a trip to Ticino: he realised that reality could no longer be understood except through a camera. During the 1970s, his hyperrealist paintings provided a window onto his life as a painter in the Lucern artistic community. His large-scale works immortalised an entire generation of artists and curators, from Markus Raetz to Urs Lüthi, Harald Szeemann and Luciano Castelli.

Paul Klee, Detachment of the Soul, 1934 (Paul Klee Centre, Bern)

As a member of the Blauer Reiter group and a teacher at the Bauhaus school in Weimar, then in Dessau, Paul Klee was at the centre of the avant-garde movements of the interwar period. In December 1933, after being summarily dismissed by the National-Socialist director of the Düsseldorf Academy, where he was teaching, Klee decided to emigrate to Bern with his wife. There he produced his late works, characterised by their large scale, experimentation with materials and boldly lined drawings.

KLAT Collective, Frankie a.k.a The Creature of Doctor Frankenstein, 2013–2014 (Plainpalais esplanade, Geneva)

This bronze sculpture of Frankenstein, located on the edge of the Plainpalais esplanade close to the skatepark, not only recalls the monster’s literary origin in Geneva but carries strong symbolic significance, as it incorporates a famously marginalised figure into the public space. Since its founding in 1997, the KLAT Collective has been active in the alternative artistic scene in Geneva. It currently has three members.

Renée Levi, Reuss, 2001 (Grand Council Hall, Lucerne)

The pictorial work of Basel-based artist Renée Levi could be said to function on two levels: that of the paintings themselves and that of the space in which they are displayed, whether in an exhibition gallery or the public space. Levi also trained as an architect. Her neon-coloured permanent installation on the wall of the Grand Council Hall in Lucerne emphasises both the architecture of the room and the function of the body that meets there.

Gianni Motti, Big Crunch Clock, 1999 (MAMCO, Geneva)

This 20-number digital clock in the entryway of the MAMCO (the Geneva Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art) doesn’t show the current time, but rather the years, hours and minutes remaining until the Sun explodes. Motti has evoked numerous natural and human disasters throughout his career, from the Challenger space shuttle explosion to the June 1992 California earthquakes. With this solar clock, he attempts to appropriate the most terrible disaster of all with his trademark blend of humour and horror.

Original article by Jill Gasparina, published in Le Temps, July 2020

Cover image: Félix Vallotton, The Gruerie Forest and the Meurissons Ravine, 1917 © Wikipedia Commons