Science safeguards Swiss cheese

Secret bacteria to trace cheese and exclusive ‘protected designation of origin’ (AOP in French) cultures are being developed by the Swiss centre for agricultural research, Agroscope.

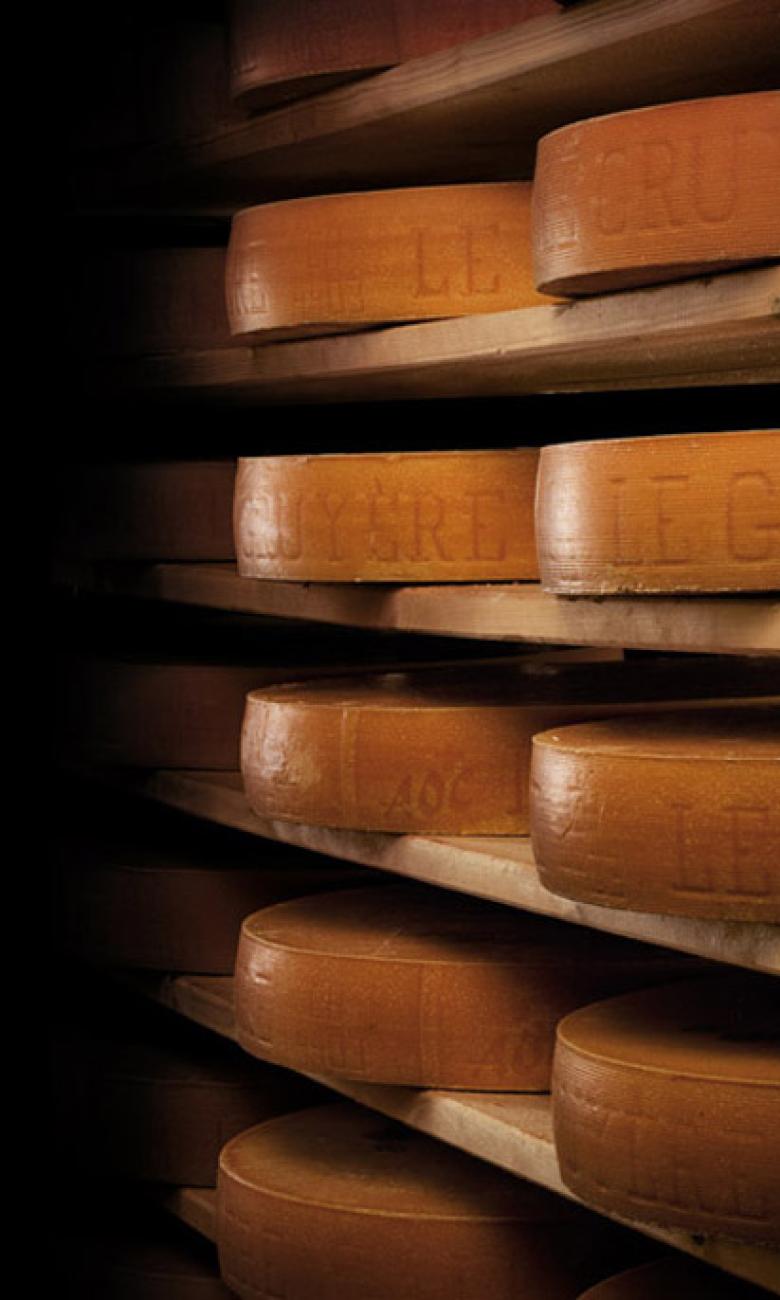

Cheese is one of Switzerland’s most prized ambassadors. Who hasn't tried a piece of Gruyère or Emmental cheese, famous for its holes? To transform milk into cheese you need bacteria. In order to preserve the distinctiveness of Swiss cheeses and catch counterfeits, Agroscope, Switzerland’s centre of excellence for agricultural research, has been developing exclusive traceable cultures to mark PDO cheeses over the past few years.

Agroscope has already been providing cheesemakers with cultures for more than a century. Today, the centre has around 40 different strains that all Swiss cheesemakers can draw from. These are mainly lactic acid bacteria used for acidification, which helps the milk to curdle and prevents unwanted germs from growing. “The bacteria influence the taste, smell and texture – even holes – in the cheese,” explains Petra Lüdin, a researcher at Agroscope. The holes in Emmental and Appenzell cheese are, for example, caused by microbes that produce carbon dioxide during fermentation.

Ancient traditions

But cheesemaking in Switzerland started long before Agroscope was created. Back then, farmers would leave their milk out at room temperature, where it would end up curdling because of natural airborne bacteria. Another method was from the rennet enzyme produced in the stomachs of young cattle. When the cheese was ready, farmers would keep some of the whey (the liquid that remains after the milk has curdled and still contains some bacteria) to use again the following day. This way of making cheese is still practised today. But it is a haphazard method that requires skill.

“Our cultures help control the cheesemaking process while raising quality and safety standards”, says Lüdin proudly. According to Lüdin, most Swiss cheesemakers use these cultures today. “A good cheese results from the right mixture of milk (the first ingredient), the way in which it is treated (expertise) and the bacteria that are added”, she adds. Agroscope's cultures, which have been developed from a collection of 10,000 carefully preserved isolates, have another plus: they help protect biodiversity as milk in Switzerland becomes even ‘cleaner’.

Making PDOs distinctive

Certain PDO cheeses have mandated Agroscope in order to benefit from exclusive acidifying cultures that set their cheese apart. The culture for Gruyère PDO has existed since 2004; cultures for Raclette du Valais PDO and Vacherin Fribourgeois PDO are being developed. In fact, developing these cultures takes around three to four years minimum.

But even if they are exclusively reserved for one PDO, you can't be gung-ho with these mixtures of bacteria. “These cultures are complementary,” points out Marc Gendre, assistant director of the Gruyère interprofessional association. “To make Gruyère, there are specifications – which require that the majority of the cultures used in the production come from artisanal operations i.e. from the whey that the cheesemakers produce themselves.” Cheesemaker Didier Germain from the Les Martel dairy in the canton of Neuchâtel only uses 2% of the cultures created by Agroscope in the total amount he needs to produce his annual 330 tonnes of Gruyère PDO. “Some people use up to 48%,” he explains. “I think we need local cultivation as much as possible. It’s up to the cheesemaker to manage the acidification process.”

Protection against counterfeiting

As well as creating exclusive cultures, Agroscope has decide to develop bacterial tracers which can be used to verify the origin of a cheese and help identify imitations. Unlike the bacterial cultures used in cheesemaking, these 'secret bacteria’ do not change the product in any way. Emmental PDO was the first to use a bacterial tracer in 2011, followed by Tête de Moine PDO in 2013 and Appenzell in 2015. Gruyère PDO and Sbrinz PDO are carrying out trials.

Counterfeiting mainly affects grated and packaged cheese, whereas whole cheese rounds can be identified more easily. When it comes to using the Gruyère name abroad, such as Graviera in Greece, Gendre can see the funny side: “You don't even need to analyse the cheese to know that it’s not Swiss Gruyère. They are completely different products with, for that matter, a strange taste in comparison to the standards we have... But as to how many tonnes are actually produced, we simply don't know.”