The Swiss who shine at sea

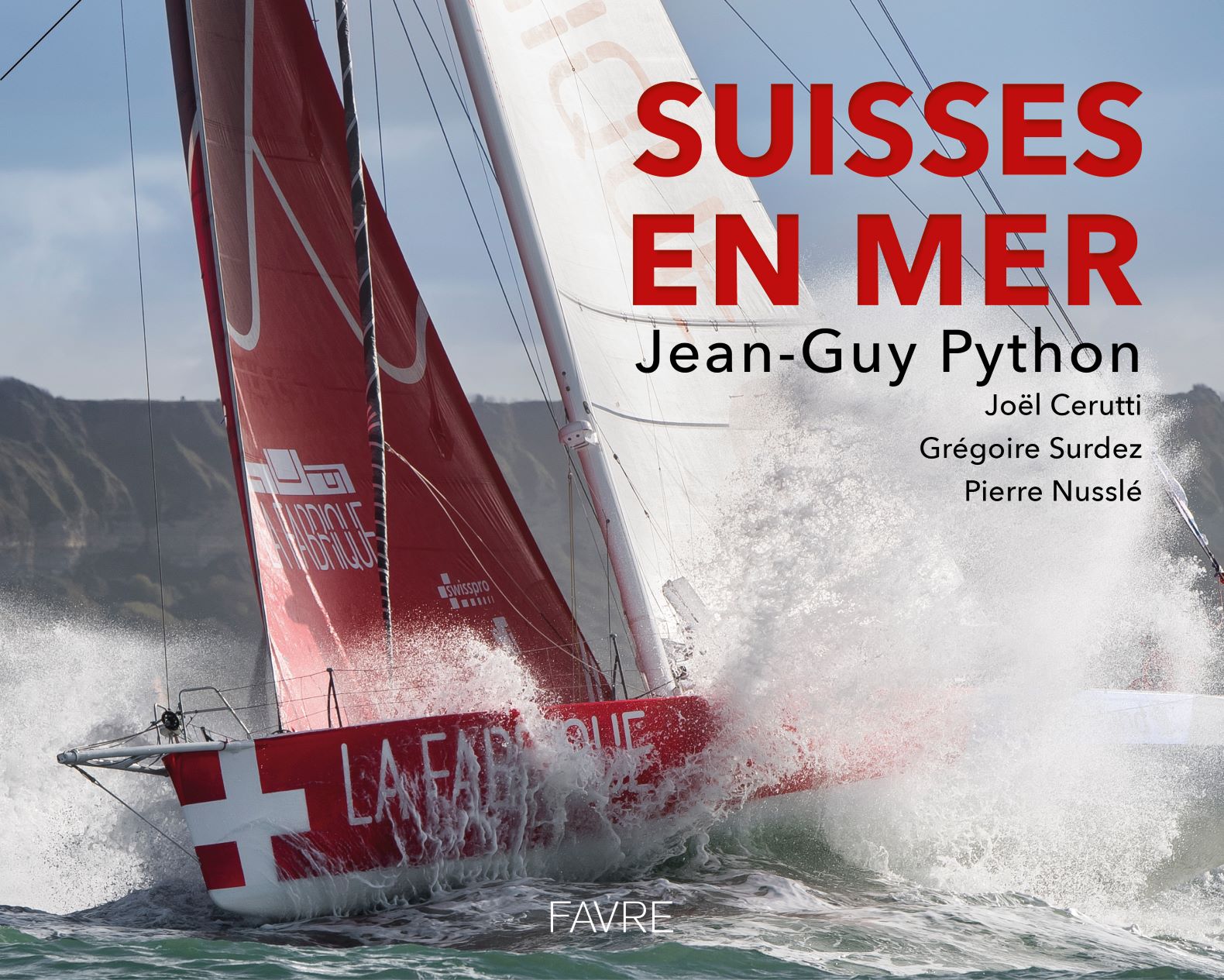

This November, Geneva-born Alan Roura is setting sail for his second Vendée Globe – the hardest solo sailing race in the world, and a veritable Swiss tradition for getting your sea legs. Despite not having their own sea, Switzerland's sailors have been taking part in the most prestigious events over the last forty years. We've talked to journalist and sailing photographer Jean-Guy Python who recently published a book on this epic Swiss tale.

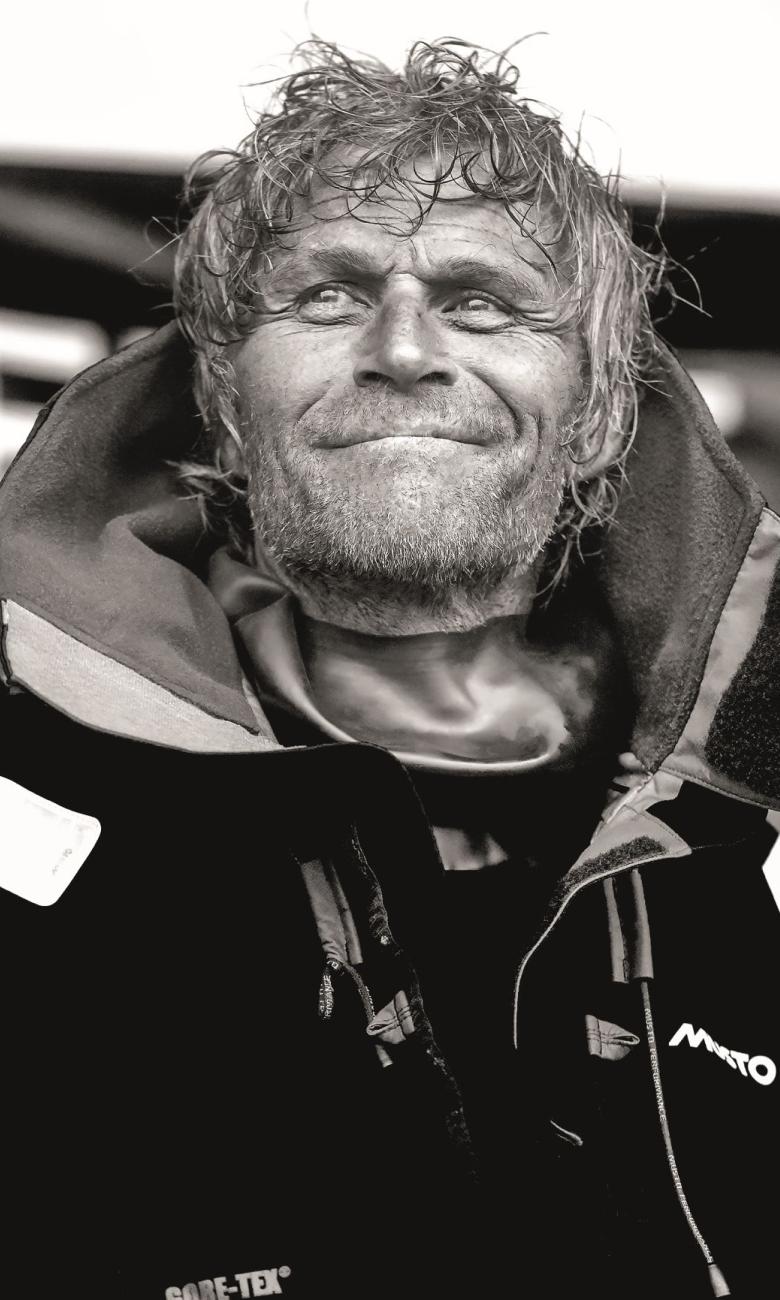

In 2016, at the age of 23, Alan Roura placed 12th in the Vendée Globe, the ultimate sailing race around the world – single-handed, non-stop and with no outside assistance. He had a modest budget of CHF 400,000 compared to the millions spent by the other competitors. He was also the youngest to compete, but this didn't stop him from repairing his rudder in a raging storm in the Pacific while hanging off a rope, earning him the nickname MacGyver. In fact, Roura even looks like he could be cast as a romantic lead. His smile and spontaneity have won over the public, and Switzerland is in his thrall.

Roura's partner Aurélia, who runs everything on land, gave birth to their daughter Billie on 9 July, but that won't prevent Roura from setting sail for his second Vendée Globe. He's kept the same sponsor, a major bakery in the canton of Vaud called La Fabrique, but because of his ranking he's also found new ones.

Thanks to this, and four years of preparation, Roura now has an even more powerful boat for his upcoming adventure. While it took him 105 days to complete the race in 2014, this year he's hoping to clock less than 80 days and secure a place in the top ten.

The sea is my life. And the Vendée is a bit like a drug for me. Once you've had a taste, you want to go back for more. It's a race that is both physical and mental. You have to battle yourself. Anything can happen, no matter how prepared you are

says Roura.

Indeed, Roura has never really lived on land. Between the ages of four and eight, he lived with his parents on a boat moored on the lake in Geneva. After that, they spent the next ten years at sea.

"I never feel totally comfortable when the ground isn't moving," he laughs. "I don't think I'll ever be the sedentary type." "Alan is a free spirit, like a poet of the seas," says journalist and photographer Jean-Guy Python, who has been following the greatest sailing races for thirty years and is the mastermind behind the recent publication 'Suisses en mer' featuring a number of beautifully-illustrated exploits of Swiss sailors around the world.

Because, as astonishing as it might seem, even though Switzerland is landlocked, Swiss sailors – from Pierre Fehlmann and Ernesto Bertarelli to countless others – have consistently sailed in the big league, securing prestigious achievements at high-profile global events over the last forty years. "There's a great deal of respect for Swiss sailors in the maritime world. Everyone knows they're a force to be reckoned with," says Python.

In fact, most of these forces got ready to do battle in Lake Geneva, a miniature sea providing them with ideal lab-like conditions. "The conditions on Lake Geneva are like those at sea – you have to stay strong in light airs and keep control when there are any changes in the wind."

Straight-backed in his boots, whether at sea or in the army, Pierre Fehlmann – known as the 'father of all Swiss sailors' – symbolises the exacting and tough nature of these pioneering seafarers. After a number of exploits, in 1986 Fehlmann won the crewed round-the-world Whitbread race aboard the UBS Switzerland. It was the first major Swiss victory at sea, with a team mainly consisting of young Swiss sailors.

"Whichever boat it was – the UBS, Gauloises or Disque d'Or – Fehlmann always took aboard the most talented sailors he'd spotted on Lake Geneva," explains Python. In fact, the Fehlmann school trained the likes of Steve Ravussin, Bernard Stamm and Dominique Wavre, all of whom went on to have brilliant careers. Born in Morges, the 76-year-old doesn't mask the pride he feels. "I turned my passion into my profession, and I gave several generations in Switzerland a taste for the open seas. I think I can safely say that I did my job." Python adds: "Fehlmann's always been straight up. He never cheats and he always tells it like it is – there’s this straightforwardness in the world of sailing, which you don't necessarily find in other sports."

The Vaudois Steve Ravussin, another strong character in the sailing world known for having a 'big mouth', was on board the Merit with Fehlmann. Their relationship was somewhat direct. "With Fehlmann, you just have to lose it once and then he'll adore you," explains Ravussin in 'Suisses en mer', using one of those turns of phrase only he knows how to pull off. Sailing lets him satisfy his love of speed. "I love the pace, the stress, the tension. If it's below 20 knots, it's not moving fast enough for me." After his victory at the Transat Jacques Vabre in 2001, the following year Ravussin was all set to win the Route du Rhum until he capsized just as Guadeloupe was coming into sight. "I was such a damn idiot, letting myself get caught," he admitted to the camera in his inimitable way.

Geneva-born Dominique Wavre, a former cycling teacher and jewellery salesman, also underwent his first ocean races with Fehlmann, notably competing in three Whitbread races as his number two. "And he had a rough time of it," says Python. In solo sailing, Wavre has taken part in three Vendée Globe races – winning fourth place in 2004, the best by a Swiss sailor so far. He's also set up the first mixed sailing crew together with this life partner, Michèle Paret. "She takes care of the mechanics, and I'm in charge of trimming. She's more the helmswoman, whereas I'm the trimmer. We totally trust each other," he explains. Paret adds: "I've always wanted to set off on the high seas together." Another Vaudois, Bernard Stamm, used to be a lumberjack before venturing into the merchant navy to fulfil his yearning for travel.

"I wanted to see the world but didn't have a penny." Trained at the Fehlmann school, Stamm made history in 2001 by breaking the transatlantic sailing record. "There are no excuses when you're out at sea. You can't cheat if you have to fight for your survival," says Stamm, who has survived a number of spectacular capsizes unlike anything any other sailor has had to face.

Another gifted sailor: Laurent Bourgnon from Neuchâtel. Nicknamed 'the little prince of the seas', his destiny was as brilliant as it was tragic. Like Roura, Bourgnon discovered sailing with his family. He was four years old when his parents sold their bakery in La Chaux-de-Fonds in order to go out to sea, taking him and his younger brother, Yvan, with them. Bourgnon was just 24 when he won the Route du Rhum, followed by two victories in the double-handed Transat race, including one with his brother. Legend has it that Bourgnon, who was so obsessed with detail, cut his toothbrushes in half in order to lighten the load on his boat. After retiring from racing, he continued to lead an adventurous life – taking part in the Dakar rally and climbing with mountaineer Jean Troillet – until in 2015 he was lost forever to the sea, during a diving accident in French Polynesia.

The most enduring of Switzerland's maritime legacy belongs to Ernesto Bertarelli, who impacted the sailing world in an unprecedented way. After having put together a yachting syndicate and employing the best sailors for each position in the crew, the billionaire from Geneva's gamble to win the oldest sailing trophy in the world paid off. The 2003 battle for the America's Cup, which is contested over a series of one-day duels, saw Bertarelli's team crush the New Zealanders 5-0 in the final stage of the race on their home turf in Auckland. Forty thousand fans gathered around the lake of Geneva to cheer the returning victors. Bertarelli successfully defended the Cup four years later in Valencia. "When it comes to competing, Bertarelli is tough and clinical above all," explains Python. He's never been interested in long-distance races. "I'm more Formula 1 than rally. I tried ocean racing once but it isn't my thing."

Bertarelli's sister, Dona, is also a pioneer of women's sailing. In 2010, her Ladycat team consisting mainly of women won the Bol d'Or on Lake Geneva. "It dawned on me quite early on that women haven't been given their rightful place in this male-dominated bastion. I wanted us to be able to do battle on the same waters as our male competitors." In 2015, she financed and took part as the only woman in a 13-strong crew in an attempt to win the Jules Verne Trophy by breaking the record for the fastest crewed circumnavigation of the globe. Bertarelli's team Spindrift failed after 47 days and 10 hours, but she rose to her own personal challenge. "When you're out at sea, there's no difference between sailors – man, woman, rich, poor. I proved that I was capable and that I belonged out there, both to myself and to other people," says the mother of three.

One of Bertarelli's teammates on the Ladycat, Justine Mettraux, is currently the only Swiss woman racing solo. Even though only seven women have taken part since the first Vendée Globe in 1989, the 2020 edition alone will feature at least six female competitors. Mettraux has set her sights on 2024, where she'll probably also find a certain Alan Roura at the starting line.