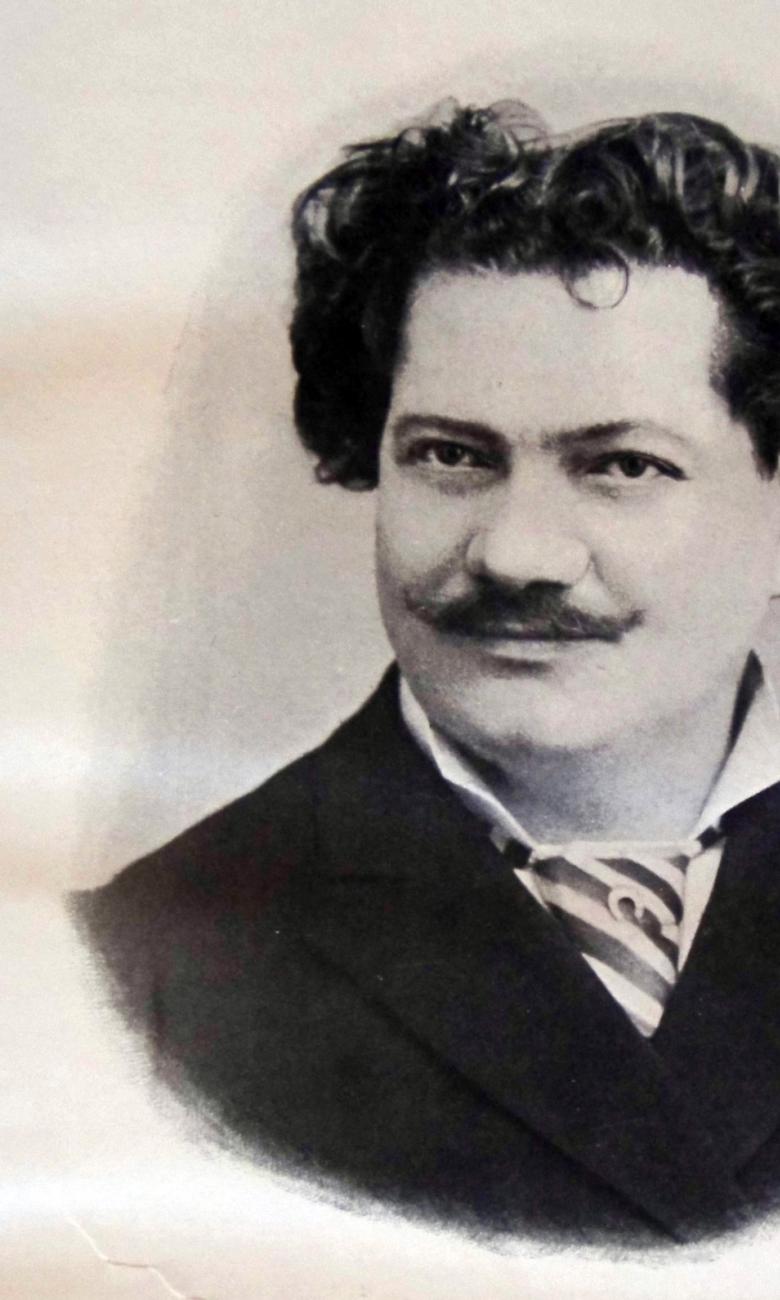

Joseph Favre, Swiss pioneer in culinary excellence

The Swiss chef and culinary writer Joseph Favre died unknown to the general public. It was nearly a century before his important place in culinary history came to be acknowledged.

From 1865, Joseph Favre (1844–1903) travelled around Europe working in the grand establishments of the age to perfect his skills as a master chef, settling in the Parisian region in 1883. An inventive, independent-minded and learned man, he was a pioneer in the science of healthy eating, wrote the first encyclopaedia on cooking and the health benefits of good food (Dictionnaire universel de cuisine et d’hygiène alimentaire) and founded the Académie culinaire de France. An elite cooking contest – the Grand Prix Joseph Favre – is now held every two years in his honour, but it took over a century for his contribution to be recognised. At the next Grand Prix, on Sunday 25 November at CERM in Martigny, five candidates selected on profile will put their art to the test before a prestigious European jury and a 1,000-strong audience made up of connoisseurs and big names in the Swiss hotel and catering industry.

Hard graft on the road to culinary excellence

Born in Vex in the Swiss canton of Valais, Favre started out as an apprentice cook in Sion. In 1865, he set off around Europe, heading first to Paris, then to Wiesbaden and London before returning to his first destination. Back in Switzerland from 1872, he worked in Lausanne, Clarens, Fribourg, Lugano, Basel and Bex and at Rigi Kulm. In 1880, he left once more, staying in Berlin and Kassel before finally settling in Paris in 1883.

Political activism and return to culinary science

In 1872, Favre was engaged in politics for a time as a member of the Jura Federation, the anarchist section of the International Workingmen's Association (First International). There he met Bakunin, who had taken refuge in the canton of Ticino and to whom he dedicated a ‘Salvator’ pudding at a dinner attended by major figures of the libertarian movement, including the Italian Errico Malatesta, Elisée Reclus and Arthur Arnould. In Favre's words, “la philosophie politique est toujours en rapport avec la philosophie pratique” [political philosophy is always related to philosophy in practice]. Favre put his politics into practice by creating the journal L’Agitatore with two fellow militants. The journal ran for two months. Favre's activism was short-lived. In 1876, with friend Benoît Malon, he rejected the insurrectionist line favoured by the Italian anarchists. Leaving the anti-authoritarian International shortly thereafter, he gradually withdrew from politics.

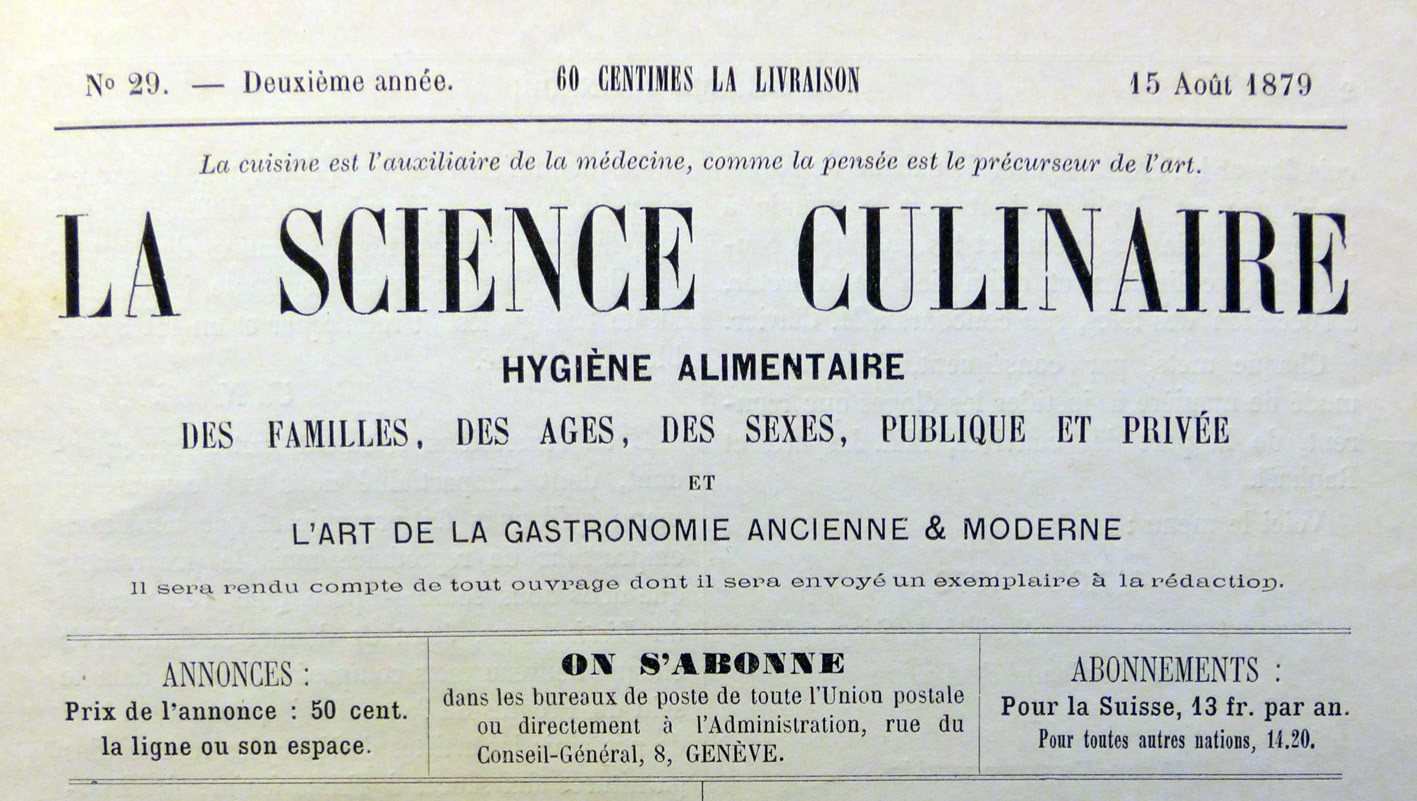

Journal La Science culinaire and first writings on ‘la cuisine hygiénique’

In 1878, Favre launched the first culinary journal written by a chef. During the six years for which the weekly journal ran, he devoted a great deal of his free time and energy to writing. The journal allowed him to develop the broad lines of his philosophy for progress in the culinary arts and to promote the rules of ‘hygienic cuisine’ – healthy cooking for vitality and long life. This new concept was based on healthy eating and food preparation, hygiene and especially food safety. It promoted the use of fresh, good quality ingredients and their health benefits, topics that Favre returned to time and again in his writing throughout his life. More than an art or a science of cooking, Favre’s ‘cuisine hygiénique’ linked cooking to healthy living in a philosophy to which he would devote his entire career.

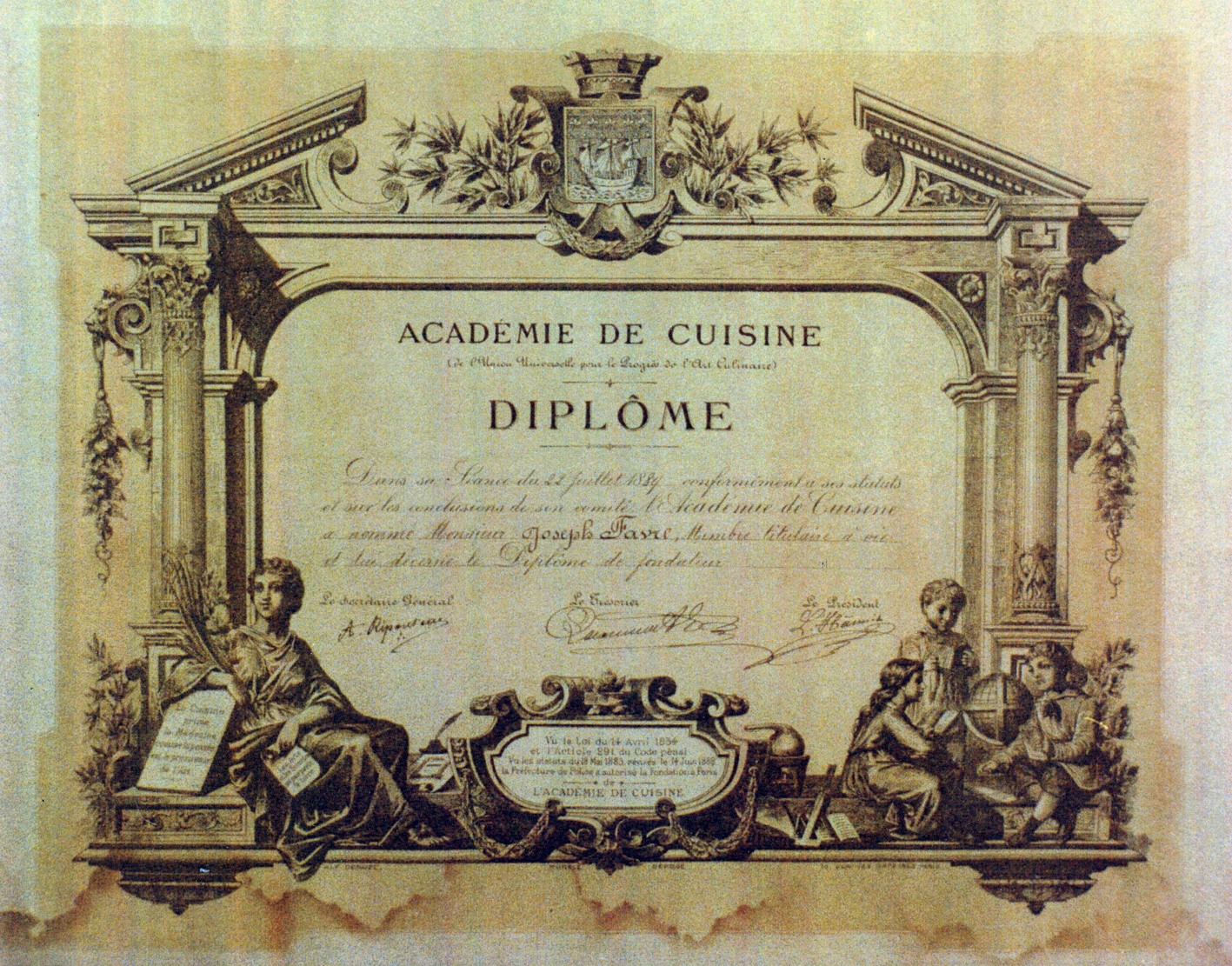

Beginnings of the Académie culinaire de France, founded in 1888

In 1879, Favre published a call in his journal for the creation of an international society of chefs organised in local sections under the name ‘Universal Union for Progress in the Culinary Arts’. A Parisian section was founded in 1882. In 1888, the Académie de cuisine de Paris was founded with Favre as its secretary. This institution sought to exploit all scientific learning connected with food and cooking to push for progress in the culinary arts. Its aim was to turn the culinary arts into a science at the service of public health. It was not until the mid-20th century that the association came to be called the Académie culinaire de France, with Joseph Favre as its acknowledged founder.

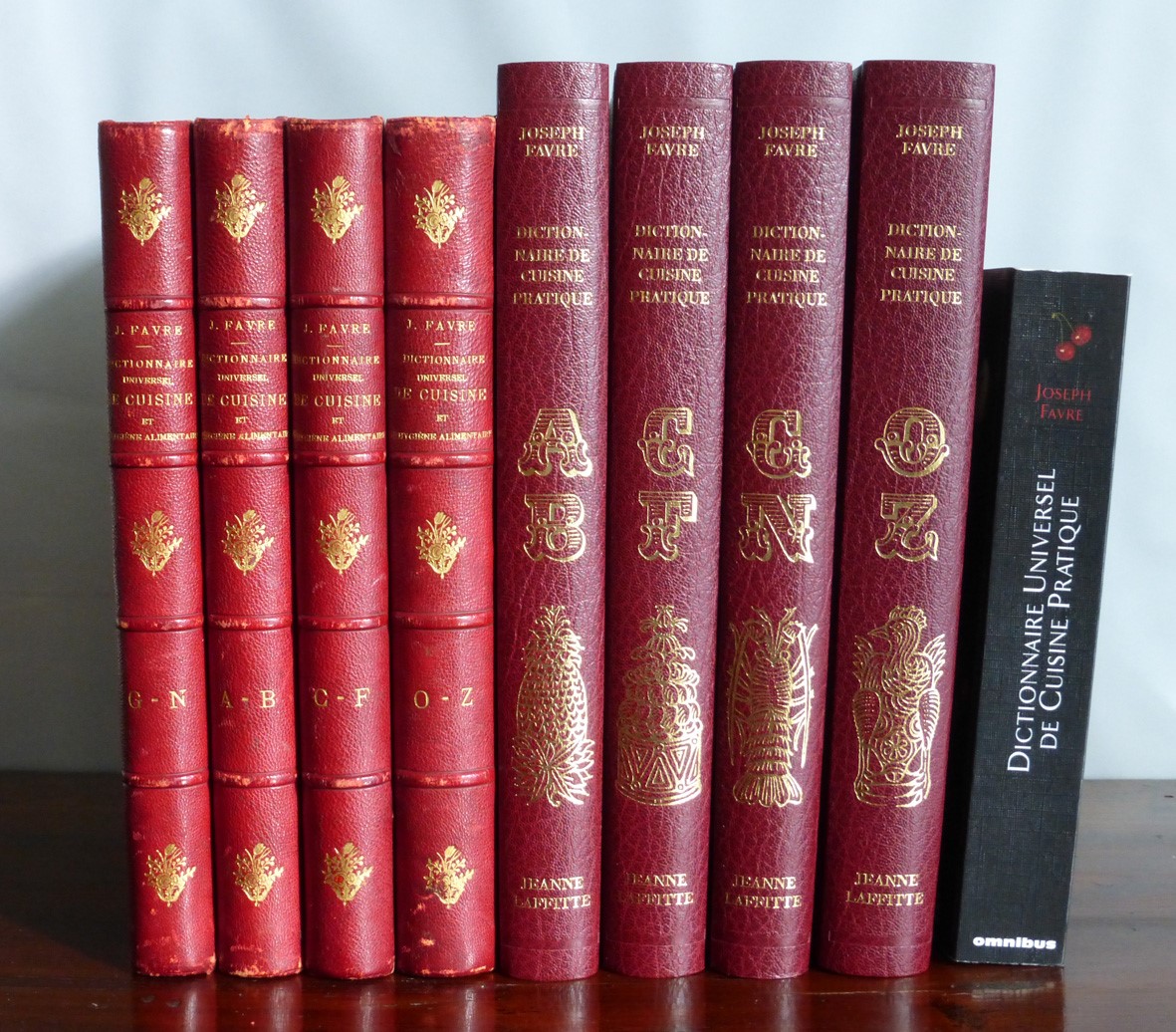

Dictionnaire universel de cuisine et d’hygiène alimentaire published

Favre’s greatest work is his four-volume Dictionnaire universel de cuisine et d’hygiène alimentaire [The Universal Dictionary of Cuisine and Food Health]. The precise publication date of the undated first edition is not known, but it is thought to have been published between 1889 and 1895. A second, expanded edition revised by the author was published in 1903 under a new title: Dictionnaire universel de cuisine pratique. Encyclopédie illustrée d’hygiène alimentaire [The Universal Dictionary of Cuisine: Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Food Health]. This majestic oeuvre, comprising some 2,000 pages of definitions and articles and more than 6,000 recipes, was groundbreaking in that it recounted the history and origin of products, discussed the nutritional value of foodstuffs and promoted healthy eating.

Recognised nearly a century after his death

Joseph Favre died unmourned by the general public on 17 February 1903. A man, a journal, a culinary academy, a dictionary, and what else? A life’s work in pursuit of culinary perfection. For Favre “cuisine, having been successively influenced by primitiveness, gluttony and refinement, has always been and still is a vehicle for civilisation. Its stages reflect human development better than any written history”. It took nearly a century for food historians to restore Favre to his rightful place in that history.